The Mission > home

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Mission click on the links below for more of the story...

|

16 Yeager’s View, In Review

The following discussion includes impressions or opinions by Chuck Yeager in his autobiography regarding his failure to achieve the record he was attempting and his resultant crash in an AST. My summary of the issues Chuck addressed in the reference section of his book serve as a lead in, only if necessary for clarity and are in standard print: The Italics are the words of General Yeager: Reference: “Rescue Mission”, Pages 171-172: This section of the book addresses Chuck Yeager’s lack of academic credentials necessary by Air Force Regulations to fly experimental test flights, which may give insight into his never achieving maximum performance in the NF-104 AST: I had no shortage of enemies in flight test, and one of them (I never learned who) discovered that I had never completed the stability and control course at the test pilot school. That is, the school was in two parts. I finished the first part, then went on to fly the X-1, skipping the second part, stability and control school, a six-month course. Without a diploma from stability and control school, I could not be certified to do flight testing. Well it was ridiculous. I had more stability and control experience than any of my would-be instructors… … I had literally hundreds of hours of stability and control work behind me when I was forced back to school. General Boyd’s hands were tied; regulations were regulations. I was sabotaged, but it was ironic having the Air Force’s big test pilot hero back in test pilot school, hitting the books. ……The school was on base. The instructors made damned sure it wouldn’t be easy for me Their attitude was right out in the open: they would love to flunk me. … So I did what I was told and counted to three or four hundred. But I always remembered those nasty sons of bitches. If they were harassing me because of a cocky attitude or because I wasn’t doing my work, I would respect that. But this was spite. I put a little red flag next to the name of each one of those guys, and nailed them the first chance I got. That’s exactly what I did, and ruthlessly, too. …Then an amazing thing happened. General Boyd grabbed me out of school and took me with him to France. Wham, bam. One day I was in school and the next day I was in a fighter crossing the Atlantic. The school’s commandant was a bird colonel. He raised hell, saying I couldn’t miss three weeks of school and expect to graduate. When we returned to Edwards, the old man marched on the test pilot school. The commandant told him, “General, there’s no way we can pass Yeager. He’s missed too much work.” The old man handed him the stability and control reports I had prepared on the XF-92 and the French jets. “Study that,” he said, “you might learn something. Yeager knows more about stability and control than you can teach him: The commandant said that might be, but rules were rules, and I couldn’t get a certification diploma without completing my course work. And without the certificate my test pilot days were over. General Boyd turned red, then purple. He slammed his fist down on the table and his voice shook that room. “Goddamn it, I’m in charge of this school. You will pass him.” And that’s how I got my diploma. Now that’s one heck of a tale, but anyone who spent time in the military and has heard of the power that General Boyd held, especially in flight testing, would find it hard to imagine any colonel took such direct opposition to his commander, especially that general, under those circumstances. General Boyd, the most notorious and powerful test pilot and “owner” Edwards base and Wright Patterson before that and all folks in test, was opposed by the school commandant? If he did that, then he was principled, adamant and deeply concerned about Chuck’s lack of technical knowledge on stability and control. Gen. Boyd, long deceased, is reported as saying it best, on page 173, about Chuck as a great and natural flyer, and of that I have no doubt. Unfortunately, the AST above 100,000 feet in a steep climb was no longer an airplane but became a space vehicle, without the attributes Chuck was inherently familiar and gifted to deal with. That airplane demanded a full understanding of space dynamics and control, not just aerodynamics. Unfortunately, Chuck had only the latter and that was more experienced and intuitive than technical. One serious consideration does arise. It is one thing to understand why an aircraft possesses certain stability and control, and the conditions necessary for that. It is entirely another to recognize and control it in flight, but, without technical understanding and theory you can do it only near the bounds you have previously experienced. Chuck had neither the technical background nor the prior experience in this one case in his flying career to get so far out of bounds. I have no doubt accepting Chuck Yeager’s vindictiveness to his instructors and those he felt wronged him as he expressed it, because I witnessed the same. He was fired from his job, as the Deputy Director of Flight Test Operations by his boss and mine, Colonel Clayton L. Peterson, in 1962. From that day on, over the years, he would vilify Peterson. On my last extended visit with Chuck Yeager and Bud Anderson, at the Air Force 50th Anniversary Air Show he accused both Colonel Peterson and his wife June of stealing government funds. Knowing her for many years until her death, and Pete over 40 years until his more recent death, I revered them and I would bet my life against that possibility, and Chuck’s growing vitriolic attacks over the years made a strong point in both their favor, but ‘that’s Chuck’, and I understood. Reference: “Going For Another Record” Page 278-283 “: This section of the Yeager autobiography addresses his attempts to set a world altitude in flying the NF-104A, AST, but is chock full of misinformation, incredible claims and invalid statements of the capabilities and limitations of the airplane. These quotes seem an effort to transfer responsibility for the accident entirely to anything but pilot error: “High engine rpm being the only way to recover a 104 out of a flat spin.” There was no possibility of recovery for a 104 in a flat spin with the use of J-79 engine power, period. According to analyses, it was the limited rpm of the jet still turning, minutes after he shut it down, which had the gyroscopic effects and probably made the spin reverse direction. He spun 3 normal, oscillatory spins to the right before the aircraft reversed direction into a flat spin, based on data from the airplane’s recorder, which was recovered. A flat spin was not unexpected with a high horizontal tail, affected by downwash from the wing at high angle of attack. “Before our students began flying them (ASTs), I decided to establish some operating parameters to learn at what altitude the aerodynamic pitch-up forces would be greater than the amount of thrust in the hydrogen peroxide rockets installed in the nose (2 x 250 lb. thrust).” Every one of Chuck’s flights in the AST was purely practice to try and establish a record, nothing more or less. I assure you that by the time he made his last flight he was struggling just to achieve the profile and not doing any testing! Not one shred of flight data was analyzed during the entire Air Force test program, including his flights until after his accident, due to budget constraints on the program, and the board president was in the line of decision on those cost constraints, in his primary assignment as the Deputy Commander of Test Operations. The only data ever saved were from the recorder in his crashed airplane, in which every bit of data for his last two attempts was saved. For understanding of technical facts concerning Chuck’s claims, please read the Space Dynamics and Control section. Briefly, altitude was not the most critical factor of control power for the thrusters, but dynamic pressure, a function of both density and velocity squared. As density approached zero, thrusters were more effective, and aerodynamic controls became useless. Once aerodynamics became nil, pitch-up disappeared with it. But spare the poor jock who allowed angle of attack above pitch-up to exist when he reentered the high dynamic pressure flight regime, due to his failure to properly maintain controls with the RCS. That is precisely what happened to Chuck Yeager, but his mistake happened in the area he had spent his whole flying career in, the dense atmosphere. Incidentally there was large margin for error between the pitch-up angle and the proper angle of attack for the zoom flight. Surprisingly, Chuck’s statements show lack of understanding of the classical aerodynamic pitch-up in his claim, as well. The only way a pilot can discern the pitch-up angle is through very controlled testing, reference my Strake Tests on a standard F-104, in the preceding chapter on the rest of my tour at the Flight Test Center. The AST didn’t provide the pilot with the vital instrument of calibrated angle of attack, a necessity for such a test. It also provided no visual angle reference of horizon, only a sky, dead ahead. The AARS only provided a reference to the optimum and far lesser alpha, of 16 degrees. Such a test as he suggested was absolutely impossible in a zoom, besides making no sense. “We thought we would encounter pitch-up somewhere around 95,000 feet.” I’m unclear who “We” was. I was the only person working with Chuck at the time and I certainly didn’t say that, because I understood pitch-up. On Col. Yeager’s two flights of December 10, 1963, he had one purpose which was to learn how to attain the highest altitude he could in his effort to be able to establish an official world altitude record. That record was his end-goal, and he had failed in all of his prior attempts. He tried for the maximum altitude on every one of his zooms, and he had to be feeling some desperation. I flew the same airplane he was flying to almost 121,000 feet. There was no intent or expectation to ever approach pitch-up, which would negate any chance for a high altitude, and entail great risk. The flight recorder later proved his maximum altitude on the two flights that day to be less than 104,000. “By then I was climbing at a steep seventy-degree angle,…” The reason Chuck Yeager never achieved high altitude was his failure to reach and hold the steep climb angle in the early climb on all his flights. From the start, in my briefings to him, I stressed that quickly attaining 70-degrees and constantly maintaining it until intercepting the optimum alpha of 16 degrees was the most important thing to attain max altitude. That took constant attention, since retrimming to help was ill-advised because of the sudden reentry and the danger of pitch-up at that point. I reiterated those things before his last flight, because we looked at his flight profile of the ground stations tracking him on the morning flight and could see him well below 70 after pull-up then increase to higher pitch, not only detrimental to altitude, but a dangerous departure because it degraded the information provided in the cockpit, which was based on assumed correct mission management. After his accident, when data reduction was completed (the first time on any of our flights), I was told by the technical advisor to the accident board, Maj. Arthur Torosian, that Chuck had climbed considerably below 70 degrees on both of his flights and would raise the pitch angle higher as he approached the top of the zoom. To do that was courting a big problem. “…and the afterburner flamed out, oxygen-starved in the thin atmosphere.” Many previous zooms showed the afterburner would continue to operate only to about 75,000 feet and had to be continually retarded and finally shut down by the pilot to avoid over-temperature or damage could result. Furthermore, the main jet was only good to about 86,000 and the same process was necessary with the main jet engine, after over-temperature was reached in minimum idle, only 250 pounds per hour of JP-4, jet fuel due to a special low idle, all due to the low oxygen content of the rare air at altitude. These were limits in all flights and had no bearing on his accident. “I went over the top at 104,000 feet, and as the airplane completed its long arc, it fell over…” The actual instrumentation from the crashed airplane was recovered and all of the data saved and evaluated. One thing the pilot never knew until checking ground track was his actual peak altitude. The airplane could never ‘fall over’ except by proper use of the nose-down thrusters during ascent, over the apogee and through and nose-down descent. It was a neutrally stable spaceplane over the top, if you achieved high altitude and would climb with the nose 70 degrees high and fall back in that same attitude with a pilot that failed to rotate the nose over with RCS, on schedule. Physics assured a reentry alpha of minus 70 degrees if Chuck completed no nose over. That is, a backward fall just 20 degrees less than straight backwards. It was necessary for the pilot to rotate nose down nearly 140 degrees on any zoom to avoid that! “But as the angle of attack reached 28 degrees, …” There could be no way to know there was 28 degrees since the aircraft had only a null angle of attack needle at pre-selected 10, 12 or 16 degrees and his was set at 16. That needle only displayed the proximity to that selected angle, but holding it on the cross-hairs was accurate and sufficient, with such a large margin between 16 and the pitch-up angle of 28 degrees. I presume he may have remembered 28 from the accident report, based on the actual pitch-up data. “…the nose pitched up.” Just more, like above. A pilot saw nothing but sky looking forward and it took a lot of confidence even to take that first peek, but served no useful purpose. Considering all the trouble he was having flying the profile he sure as hell had no time to even take a peek. Chuck’s performance to that point should not have bred confidence, but if he had it that view gave him no information on attitude. Again, the AST could not ‘pitch-up’, if it reached the low q of a max zoom, until it fell back into atmospheric pressure because of negligible dynamic pressure (as low as 2 to 10 PSF). Under the conditions Chuck put himself in, he was fully backward with an alpha as high as 160 degrees when pitch-up occured at only 28 degrees. He was only 20 degrees shy of falling backward with his nose pointed straight up. At the top of the maximum zoom of the AST, the dynamic pressure was so low that aerodynamic induced motions were nil (including pitch-up and they could readily be overcome with the thrusters if a proper climb angle had been maintained from pull up. But add yaw induced by the spinning jet turbines to Chuck’s mistakes and you had perfect spin conditions. “ That had happened in the morning flight as well. I used the small rocket thrusters on the nose to push it down. I had no problem then. This time, the damned thrusters had no effect. I kept those peroxide ports open, using all my peroxide trying to get the nose down, but I couldn’t.” Data reduction by engineers proved that Chuck luckily got away with almost the same thing in the morning as the afternoon, but his luck finally ran out. It was not news to any F104 pilot that flight controls would not overcome full-blown pitch up and flat spin, in normal atmosphere. Chuck was already falling backward when he used the RCS constantly, at which point they were incapable of correcting his serious problem. If the attitude was not constantly controlled with thrusters using information presented by the crossed needles of the AARS gage, of course, the aircraft could fall back into the atmosphere where the thrusters became useless. Look at it more simply. If you pulled up the AST or any F-104 to 70 degree pitch, lets say starting at 400 knots and 10,000 feet, with full power, held it and cut back to zero power and continued to hold the nose up, there would be a point where it would be too late to try to push the nose over, with aero or RCS controls or both. You would do exactly what Yeager did. Fall backwards still at 70 degrees pitch but a minus 140 degrees angle of attack, where no airplane can fly; a good opportunity for tumbling or for a flat spin to develop. This is an explanation of Chuck’s flight, with the low altitude to make the point intuitive. But it really doesn’t matter how much higher it is presumed just as long as it never got high enough and continued fast enough in order to stay outside atmospheric effects long enough for the RCS to rotate AST through the necessary 140 degree nose-over before falling into the atmosphere again. “ My nose was stuck high, and the damned airplane finally fell off flat and went into a spin.” My first Maximum Zoom was successful to almost 119,000 feet in spite of miswired controls, which proved conclusively that the AST had a great deal of control power safety margin in its design, with all three directions miswired to 100% error with each operation. In fact it was designed with margin even with only half of the thrusters functioning! I'm afraid Chuck was again stretching for a scapegoat on his accident, and it certainly wasn't the Reaction Control System. The data from both flights showed that he had come perilously close on his morning flight also, but fortunately, he had applied nose-down thrusters before he fell back into the atmosphere, probably because he had flown a better and little steeper profile so made it as much as 4000 feet higher and had more rotation time to recover to a nose down attitude before encountering pitch up. Most probably, Yeager always had pulled up too shallow to achieve the higher altitudes and tended to raise the nose later, then waited too late for the nose-down controls with the thrusters, based on the data from the last two flights and the lack of altitude on all his zooms. In that last flight the data proved that he had given up so much energy in low climb angle before he finally got the nose up, that the rocket motor was still burning as he reached the top, giving him a false sense of still climbing, when he was starting to fall backward. The liquid rocket, with only 6000 pounds of thrust could not stop a rapid backward slide of the AST. He had not even come close to flying the necessary profile for success of his mission. “The data recorder would later indicate that the airplane made fourteen flat spins from 104,000 until impact on the desert floor. I stayed with it through thirteen of those spins before I punched out. I hated losing an expensive airplane, but I couldn’t think of anything else to do.” Something else did occur which was drag chute deployment at 17,000 feet in the spin. That act demonstrated how well Chuck Yeager reacted under great duress, once he was back in his element of aerodynamic flight. It is notable that the spin was completely stopped by the parachute and with the airplane in a steep and oscillatory dive, but the spin reinitiated when the chute was jettisoned, shortly before Chuck ejected, at 7000 feet. Speaking about the bail out, landing and recovery Yeager says: “I was dazed, standing alone on the desert, my helmet crooked in one arm, my hand hurting so bad that I thought I would pass out. My face didn’t hurt at all. I saw a young guy running toward me; I had come down only a mile or so from Highway 6 that goes to Bishop out of Mojave, and he watched me land in my chute, then parked his pickup and came to offer his help. He looked at me, then turned away. My face was charred meat. I asked him if he had a knife. He took out a small penknife, unfolded the blade, and handed it to me. I said to him, “I’ve gotta’ do something about my hand. I can’t stand it any more. “ I used his knife to cut off the rubber-lined glove, and part of two burned fingers came off with it. The guy got sick. Then the chopper came for me. I remember the medics running up. I asked them, “Can you do something for my hand” It’s just killing me.” They gave me a shot of morphine through my pressure suit. They couldn’t get the suit off because it had to be unzipped all the way down, and then I’d have to get my head out through the metal ring, but my face was in such sorry condition that they didn’t dare. At the hospital, they brought in local firemen with bolt cutters to try to cut that ring off my neck. It just wouldn’t do the job. Finally, I said, “Look in the right pocket of my pressure suit and get that survival saw out of there. It was a little ring saw that I always carried with me, even on backpacks, and they zapped through that ring in less than a minute.” I was very impressed ever since that day with how lucid Chuck was when our Flight Test H-21 helicopter, in which test pilot Phil Neale and I picked him up from the desert floor, standing next to the airplane’s hulk. Chuck talked to me about the accident as we flew back to the base hospital. But Chuck Yeager might have been in shock then and I couldn’t tell it, or has lost his memory since, because those are not the facts. Bud Anderson did fly over Chuck long enough to see him land safely, then Bud had to return to base on low fuel, a fact Bud stated in Chuck’s autobiography. At the moment I heard him announce he went into his spin, Phil Neale and I ran to the H-21 chopper kept outside the Operations Center for such purposes. We heard Bud Anderson radio that he saw Chuck land safely in the chute and Bud was leaving for home, because of fuel. We approached, shortly thereafter to see Chuck standing close to his airplane. Ours was the only helicopter available to pick Chuck up and Phil landed us at the helipad by the hospital, where the medics saw Chuck, for the first time. They may have given him the pain killer injection then and his memories could well have been the ravages of stress and pain, and he obviously had both. But, he talked in detail with me about the accident experience in about 30 minutes alone in the back of the chopper in route to the hospital. The same was true of Chuck’s reporting a young traveler, because we were there too close behind Bud for that to have occurred and, when I recall how critically burned Chuck appeared to me, I know that no man would have driven away and left him alone like that. Also, we would have seen tracks and dust from a vehicle in that open desolate desert, from miles away on our approach, and Bud would have seen him. Bud just smiles at the mention of that young fellow. Do I think Chuck Yeager fabricated an excuse for his event over the top and the resultant failure in his accident? Undoubtedly, he did. It is possible it was due to confusion by events to which he could not relate, or to merely salvage his image of invincibility. Here was a pilot, one of the best stick and rudder flyers and practiced test pilots, one of the most intuitive in responding to the unknown events of flying for all time who found himself in an environment, in his mind, which is something that he has contended with and conquered for so many years. But he had not accepted from all our briefings that it was not that same environment, and skills to conquer it were different. The AST responded in a ways different than any airplane because of a different environment. But little did I expect that it would be his failure to control climb angle in the environment that he understood so well that would be his downfall. Chuck will never comprehend what happened so cannot analyze it except on his terms. But there is that other possibility, stated in the words of one of his long time associates and competitors in flight testing, the famous and first X-15 test pilot A. Scott Crossfield, who I expect read Chuck’s book and, in Scott’s recent speech at the Hiller Museum in Santa Clara, CA, he referred to Chuck Yeager as, “That well known novelist.” Well, I have seen a long line of actions by Chuck Yeager to polish and expand his the image, and that not only fed his ego but his bank account. But the one that impressed me personally, was the fact that at a time when his image needed a boost more than ever since his famous Mach 1 flight, I was replaced in my only opportunity to establish a record, by him, who held so many records in the past that the Air Force issued the regulation denying any pilot more than one record unless made on the same flight or project. And at that exact space of time he was in close contact with three powerful folks who possessed the means to assure he got it. I stand with Scott Crossfield’s opinion, and know the evidence is too powerful to doubt it. Sadly, Chuck’s selection for the task, without proper testing, was a disservice to both him and the folks who created a unique airplane that had the opportunity to develop capabilities that have since been overlooked for almost four decades. Throughout, I have mentioned engineering whiz Bob Hoey and his expert knowledge of the AST along with the board developments and investigations. I recently asked Bob to reminisce about the program, especially his conclusions about it. From an engineer’s point of view, I would never challenge Bob, I have seen him at work! From a pilot’s standpoint, I would only disagree slightly on one point he makes. I do not believe that the AST would have been too difficult for astronaut candidates, if they were engineers as well as proven experienced test pilots. THE NF-104A AEROSPACE TRAINER; IN RETROSPECT by Robert G. Hoey “The NF-104A was conceived as a low cost means of exposing astronauts-in-training to the real space environment, including some of the required subsystems and flight control systems. A modification to Lockheed's F-104 appeared to be a reasonable way to do this. The NF-104A did, in fact, include subsystems that were necessary for space flight, and did, in fact, enter the true space environment for a short time period. The airplane performed as designed, a tribute to the Lockheed design team and the flight test community. The potential use of the airplane in a training mode, however, was questionable due to the short exposure time and the high risk associated with each flight. It was a single-seat aircraft, which meant that there was no instructor available to correct errors or bad decisions by the student. Additional information obtained during the test program further degraded the airplanes potential as a trainer, especially with regard to the handling qualities. Aerodynamic controls are approximately rate-command; that is, a particular stick deflection will produce a roll rate. Reaction control rockets, as used in the space environment are acceleration-command; that is, a particular stick deflection will produce roll acceleration. The piloting technique is quite different between the two systems. Smooth, proportional commands are used for aerodynamic controls, while short, pulse commands must be used for reaction controls. There is a third control method, used in some space vehicles, which uses the characteristics of a spinning mass (gyroscope) to change the attitude of the spacecraft. When a torque is applied to the gyroscope, the attitude changes in a direction 90 degrees from the applied torque (an applied torque in pitch will produce yaw). The NF-104A transitioned from the aerodynamic control region into the space control region and back in less than 1 minute. The student pilot had to adapt, and transition from aerodynamic controls to reaction controls and back again, within this time. He also had to simultaneously perform a very large change in pitch angle to realign the airplane for entry using some combination of the two control features. Failure to perform this alignment could result in a deep stall condition as encountered by Gen. Yeager. The discovery during the test program of significant gyroscopic effects from the spinning engine during this same critical time period complicated the piloting task even more since the application of the required nose-down pitch control input caused a gyroscopic yawing response in the airplane. Performing a successful zoom maneuver in the NF-104A was a very demanding task - probably more demanding than any of the maneuvers that might be required in an actual space vehicle. Limiting the climb pitch angle served to maintain a higher level of aerodynamic control over the top, but, of course, that tended to defeat the available reaction control training. Several efforts were undertaken to try to maintain higher engine rpm over the top to allow for more reliable engine restarts after entry. These efforts would tend to amplify the rather confusing gyroscopic effects. Braking the engine after shutdown would have eliminated the gyroscopic effects as a complicating factor, but would have resulted in dead-stick landings after every zoom mission. In retrospect it appears that the NF-104A airplane and subsystems performed as designed and did, in fact, produce a valid space environment for a short time. The necessary piloting tasks to safely control and recover the vehicle, however, tended to detract from the training aspects, and probably were more risky and demanding than was appropriate for student astronauts.” |

| previous section | next section |

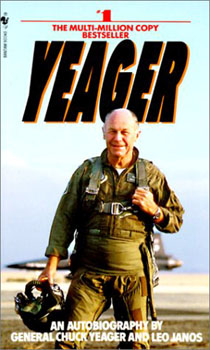

The following are Chuck Yeager’s statements

from: ‘YEAGER, AUTOBIOGRAPHY’ by General

Chuck Yeager and Leo Janus, Bantam Books July

1985. That autobiography is a view of Brigadier

General Chuck Yeager’s life, with emphasis on

his flying career. The book includes a brief

section on his NF-104A, AST experiences and his

accident in which the airplane was lost after a

flat spin from which Yeager ejected and was

injured by fire.

The following are Chuck Yeager’s statements

from: ‘YEAGER, AUTOBIOGRAPHY’ by General

Chuck Yeager and Leo Janus, Bantam Books July

1985. That autobiography is a view of Brigadier

General Chuck Yeager’s life, with emphasis on

his flying career. The book includes a brief

section on his NF-104A, AST experiences and his

accident in which the airplane was lost after a

flat spin from which Yeager ejected and was

injured by fire.