The Mission > home

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Mission click on the links below for more of the story...

|

||

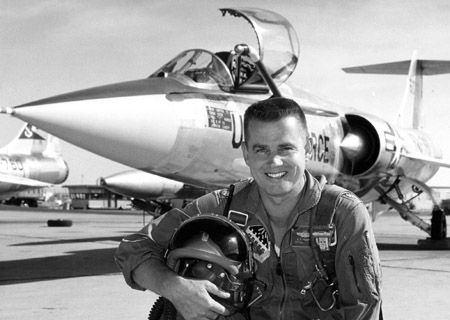

9 A Big SurpriseCol. Peterson called me into his office and told me that Col. Yeager was going to be flying the AST in short order and that Air Force Chief of Staff, General LeMay had designated him to establish the official world’s altitude record. I knew that Pete and Chuck were alienated because he refused to let Chuck leave his job as Deputy of Flight Test to go wherever and whenever he pleased, which was Chuck’s lifestyle over the years. Pete had told him to find another job or get to work. Chuck chose to be the Test Pilot School Commander, with little or no tie-downs, since it was well organized and the incumbents already ran it. Interesting things pop out in Chuck’s assignment. The school had always included an analytical side, especially the stability and Control half of the test pilot school, and it was that half that Chuck had failed when he attended TPS. The advent of the ARPS addition, leading the AST kicked the technology and engineering studies up a few notches higher to become a high tech engineering atmosphere, not Chuck’s realm by his own admissions, in his autobiography.

Chuck took over shortly before I graduated from ARPS. It was at that point that he had tried unsuccessfully to move the AST test program under the school, and lost that battle, exacerbating the breach between those two colonels, Pete the senior in rank and Chuck holding far more influence. Over the years, including the last time I spent some hours with Chuck and his friend and famous WWII Ace, Bud Anderson, 1997 in Las Vegas at the Air Force’s 50th Anniversary, Chuck grossly disparaged Pete’s character, which was not a first in my presence. He knows that Pete, who is no longer with us, is my idea of an outstanding officer and gentleman. Pete was truly upset with the decision, attributed to Gen. Curtis LeMay, Chief of Staff. The only possible explanation was Chuck and his supporters arranged that, because Chief’s of Staff were certainly too busy to notice such a minor issue without a powerful sponsor. Facts back up that opinion. A lot had happened in a period of months before the start of Air Force tests and Chuck Yeager flying the AST. One of those was preparing a famous aviatrix and one of Chuck’s best friends, Jackie Cochran, to fly for a Women’s closed course world speed record in the F-104. Jackie, was no spring chicken but had a long-standing competition with another Jacqueline, the daughter of the French President, to set flying records. Jackie had the American Air Force to support her and Jacqueline the French Air Force and the French woman was one up at that time, so Lockheed had prepared and paid for Jackie’s attempts. Jack Woodman described to me her check out in the two-place airplane, after which she flew solo with Chuck or Jack on her wing to talk her in on landings. She had great confidence in Chuck and she was middle age by that time. The most demanding part of that record, which is run on a racetrack path at high altitude was maintaining it within the narrow altitude limit. Jack told me at the time that as hard as they worked, she could not do it. The problem was solved when Lockheed added automatic altitude hold to her airplane. She didn’t have to control anything but ailerons (wing roll) throughout the record runs and thus she succeeded. My point in reciting these facts is demonstrating the ability of one civilian to call upon the U.S.A.F. in this manner, because the government ultimately paid for it, rest assured. I feel sure it was also germane to Chuck’s flying for a record, after so many years. Jackie was famous for many years and had made friends of many early flying heroes, most among the military. She married Mr. Floyd Odlum, who was a billionaire industrialist, owner of the Atlas Corporation, a holding company with large controlling stock interests in companies, including aircraft manufacturing. In particular he held a big interest in Convair, which had a large plant in San Diego. Also among Jackie’s supporters was Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force General Curtis E. LeMay. Add Chuck Yeager and that foursome was very well connected and powerful. A prime example was the extended trip which Chuck and Jackie took earlier, in her Lockheed Lodestar, a twin-engine passenger airplane. They flew from the America to Russia. What was astounding, but true, was that those two flew throughout the U.S.S.R. at the height of the cold war with the approval of both governments who were sworn enemies and could agree on nothing, and they had few constraints, flying without commissars or passengers to oversee their flights. This powerful foursome influenced every aspect of the AST program from that moment on. Pete urged me to avoid getting involved with Chuck’s check-out, advice which I respectfully begged to decline. I had the knowledge base of the AST, but the handbook wasn’t yet written. I told Pete that I felt obligated, and he understood. It is important to anyone to receive recognition in life’s work and the official world record would have been a once in a lifetime affirmation for me. This irreversible decision has bothered me more in recent years than it did at the time it happened. Quite frankly, until long after my final retirement from a second career, almost 30 years later, I seldom looked back on those events of the past, in great measure because I greatly missed them and chose not to dwell on my flying career, to enhance my new dedication to managing some vitally important NASA and military programs for 23 years, as a civilian. These last 12 years in retirement have added to my angst on the issue. A little of that may be attributable to jovial goading by some dear Air Force friends, but more than anything it is probably the lack of a challenge of sufficient risks in true retirement. It took a long time to realize that it was not the brief surge of adrenaline that came with moments of high risk that stimulated the urge to face them, but the lasting satisfaction of overcoming them. That realization led me to select assignments in my civilian career that provided a higher level of opportunity to fail to achieve satisfaction of accomplishment and fill the void of not flying. |

| previous section | next section |