Chapter 5 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

|

|

|

Chapter 2 Aerial Combat |

|

Chapter 3 Flight Test |

| Chapter

4 Approach to Space |

|

Chapter 5 Limited Weapons, Assured Defeat! |

|

Chapter 6 Limited War: Unlimited Sacrifices & Defeat t/c |

|

Chapter 7 End of the Beginning t/c |

|

Chapter 5 - Limited Weapons, Assured Defeat click on the links below for more of the story... i. Limited Feedback - ii. Back to School - iii. 388 Tactical Fighter Wing - iv. Rolling Thunder - v. Rules by Fools - vi. The Bridge - vii. Good Morning Vietnam! - viii. Home Again |

||||||

Rules by FoolsThe most onerous thing that stuck with me throughout the tour, and to this day, was the nature of the “Rules of Engagement” which so often imposed added risks to life for our men in order to avoid collateral damage to the enemy. We had to pass repeated tests on the rules and the standing joke on failure was the simple question, “What do they do, send you home?” The obvious was you passed, period! These were just bottom of a hierarchy of orders and resulting rules that killed the military in Vietnam, unnecessarily. Beginning with the concept of Measured Response to the NVN actions. The results of the political attitude was so onerous that it resulted later in the “Weinberger-Powell Doctrine” of 1994, in which Gen. Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of the military, defined the ‘Necessary Conditions for Committing Troops’ in the future (which had been ignored for Vietnam): Those conditions were stated as: Vital national interest; Other options exhausted; Commitment of sufficient force to win; and Determination to finish the job. Some, if not all of these have since led to casualty avoidance of our military, but that seemed not to be a serious concern in Vietnam. Sure, we have a few military goof-heads like a retired Army Chief of Staff, claiming that reducing American ground casualties by using air power in Kosovo and Serbia in 1999 was immoral, when Americans were there doing the job and taking the risks for Europe’s nations that requested us. And retired Marine Lt. General Bernard E. Trainor wrote abut that issue in the Boston Globe: “Despite the accuracy of the air attacks, too many civilians were killed while allied combatants avoided risk. This turns a principle of a just war on its head...specifically, the obligation to protect the innocent at the expense of the warrior.” A small few (more candidly, few “small’) ground force leaders were miffed by their exclusion in those campaigns, but their rationale is ridiculous: Defining the humanity index of a war on the willingness of a nations leaders to accept losses, which I presume made Russian rights under Stalin and Germany’s under Hitler, the most just wars of modern history. The very liberal “Human Rights Watch” put the total civilian casualties at 500 in Kosovo and Serbia, and we had no casualties. Would thousands of ground troops have reduced those 500, and even if that had been certain, why should hundreds or thousands of American youngsters have been sacrificed, for campaigns taken on the request of Old Europe? The Vietnam War was conducted as Gen. Trainor would have had it. Many rules were ridiculous, for example, if we had hung bombs in the most heavily defended areas we had to carry them off to dump them, instead of instantaneous emergency release. The rule imposed a very high risk, especially with one hung 3000-pound bomb. Imagine how suddenly the Thud would roll over and crash at 5 g’s, with an inertial weight of 15,000 pounds differential between the two wings, one with a bomb hung half way out its length. It forced a very gentle pull-up from the dive to just miss the ground, thus a deeper penetration into the flak and no evasive opportunity for escape, until miles away. And in almost every case, the emergency ejection of a bomb on its rack resulted in a dud. And the stated purpose of such rules was to keep us from inadvertently killing any of the North Vietnamese gunners or their friends, relatives, or neighbors. Unfortunately that administration’s rules were not to endanger the enemy citizens if the lives of young Americans could be risked to avoid it. Here’s an actual mission example of how a few other of the many rules reduced our ability to do great damage, when we got an upper hand on the enemy. I flew on this one. The target was an enemy truck park in northern Laos, identifiable even at our cruise altitude by the numerous dirt roads leading to that jungle area. We had passed by many times but never could attack because, as scuttlebutt had it, the local chieftains were bribed by NVN. We lost many pilots going for less valuable resources of the enemy, which had fierce defenses. Maybe the NVN didn’t pay the parking permit that day, because both Thud wings were suddenly diverted from our scheduled strike force attack to hit it. First we dropped our bombs, then we took turns strafing with our Gatling 20 mm cannon. There must have been pandemonium in that jungle area, which had been a sanctuary. Huge explosions and fires erupted under the trees, and trucks went flying into the air. Obviously, there was great destruction but probably only a small portion of what must have been stored in such a large area of many square miles, and we faced no significant defenses. The mission didn’t count toward our ticket home (100), but who cared with such results, and we hurriedly returned to base, confident we would rearm and return to destroy more munitions headed to the south, and expected that would continue until darkness, or explosions ceased. After all, by the next morning they might have everything valuable moved away. We did not return that day or ever again, to this or any other of those areas, although I believe we probably did more to disrupt the war in the south on that mission than all but a very few to the north. Apparently, the NVN learned their lesson and paid the Laotian politicians more! What made these situations so hard to accept was that on occasion we had weather aborts and could have decimated places such as this, and we knew where they were. Instead we dropped safe tied bombs in the jungles. RADAR FOLLIES What happened to us for a while I could best call folly created by national leaders, though disaster might be more to the point. Our Thuds had ground radar, but so limited that they were not even effective for navigation and absolutely useless for attack in Vietnam. They were not even maintained in working order. In their defense, they could have done very well on finding a major metropolis worthy of a nuclear weapon in their intended design mission. The following italicized facts written by Spence Armstrong describes a prime example of the extremes to which The Pentagon stretched to satisfy political gains, no matter the military risks. I can think of no one more qualified since “Sam” as he is more widely known showed his courage by flying more of this dangerous and unrewarding missions as any others of us. I have interjected commentary between segments: “About six months prior to my arrival, the Air Force had responded to the fact that the U.S. Navy A-6’s could use radar to bomb North Vietnam when low clouds prevented the Air Force from dive bombing. The solution, approved by General Ryan the Chief of Staff, was to direct the F-105F’s to do single ship, night, level bombing using the pitiful radar with which all F-105’s were equipped—including our F-105D’s. Since the EWO’s weren’t trained in this radar delivery, pilots occupied the rear seat for this mission. Newly arrived, junior pilots found themselves in this unenviable position. Several of these aircraft did not return from their night missions. We never did know what happened to them. Bob Stewart, the number one graduate of West Point ’56 and a friend of mine in Primary Pilot Training, was a casualty of these missions just before I arrived. Since this mission was so patently dumb, the crews called themselves “Ryan’s Raiders”, a not too reverent reflection on then Chief of Staff. They even designed a shoulder patch, which depicted an F-105F with a huge screw penetrating it from the bottom. The cessation of that abortive and costly experiment was merely a hiatus until the bad weather began to impede our strike missions, once again. That time we began flying a new kind of radar attack to Pack VI: ground-radar controlled missions, whenever weather would not allow us to attack visually with the strike force. Small teams of American airmen were moved into mountainous areas of Laos and Cambodia and set up ground radar sites. Those teams lived in significant peril, some in areas where international agreement denied it, so they were offered little or no ground protection. That decision was made to guide our strike missions above the clouds under radar control. This method was dubbed, “Sky Spot”. It seemed incongruous that we were flying under rules of engagement that placed us at added risks to protect the enemy from collateral damage, yet we were dropping bombs above total cloud cover in level formation like B-17s in Europe. Especially since we had been admonished by Washington for putting NVN populace at risk, just a few month before: On the 5th of October, all of the pilots were called to a briefing in the Base Theater. Col. Ed (Red) Burdette, our wing commander had just returned from a mandatory meeting in Saigon with General Momyer, the 7th Air Force commander. The purpose of the meeting was to relate to the wing commanders of all of the combat wings the concern that existed in Washington that civilians were being killed in our bombing attacks. Col. Burdette dutifully passed on the admonition to be more accurate in our bombing—he never alluded to the fact that he had been instructed to make this speech although we all knew this was the case. He was true to the modicum that commanders never alibi their directions on higher headquarters. The term Sky Spot itself was a deceit although the bombs were dropped from a spot in the sky, that’s obvious, but no one could know where they would impact the ground. Deceit was explicit in the certainty of huge errors of maps and radar, leveraged by great distances between radar and target, added to the inaccuracies of high altitude releases in level flight. All our worst dive-bombing attacks in a month could never achieve the risks to civilian population from 96 bombs scattered over an unknown area in an indeterminately broad pattern on a 16 ship Sky Spot! Yet we were chastised for the former ordered to do the latter. And, the crowning blow was that we were directed to be in tight formation over target. This was like sending us a death wish! When flying over cloud cover only our ECM formation offered us any security that the surface to air missiles might miss the airplanes as they passed through that broad formation. Not only was protection negated, in tight formation, our ECM pods helped the enemy by giving a better ‘paint’ of us and a very high probability of a kill, by the SAM crew merely selecting their proximity fuse at launch! Sky Spot missions were of absolutely no military value, but allowed Washington to continue adding to the tonnage count in America’s newspapers, during inclement weather. Bomb tonnage and enemy casualties in SVN were the major indicators claimed as measure of success by the Administration, but meant squat militarily. Spence recently read a book (which considering his graduation from Annapolis is amazing) on those missions: ‘One Day Too Long’ by author Timothy Castle. Here is what Spence said about the book and his own experience: “It tells the story of the clandestine radar site that was placed at Channel 97 in Northern Laos. Since we were signatories to the 1962 Neutrality Treaty for Laos, we had to do things covertly. In fact, we weren't even supposed to be bombing there and Air America really didn't exist! He talks about the Commando Club missions run out of what was called Lima Site 85 co-located with the Channel 97 TACAN. I think that I flew on every one that was flown into Pack VI until we stopped that fiasco after Col. Burdette was shot down. The NVA scaled the mountain on March 10, 1968 and killed 11 Air Force personnel. Some were lifted out by helicopter but the folks in Saigon were reluctant to evacuate the folks even though they were under artillery attack from a sizable NVA force. They had the stupid idea that the site was directing the missions into Pack VI. There were other radar sites that directed Commando Club missions in the Lower Packs, Barrel Roll and Steel Tiger in Laos…..I also have a record in my log about being diverted to Channel 97 (that's the way we referred to it) on March 11. They had us strike some targets a few miles from the mountain. I know now that the folks were already dead or evacuated at that time.” Don Hodge, an excellent Flight Leader, recalls a mission he flew in an impossible effort to protect those American’s, some known to have been savagely executed: “ I remember Sandy (Forward Air Controllers in Laos) spotting a target at the base of a sheer cliff in the area of Channel 97. I dropped my 6 /750 pounders on the smoke & made 20 mm passes, about that time. Later read the NVN Commander’s version of what happened that day. He had an overwhelming force that killed all of the Americans, however the exact date was not disclosed in it.” One victim of this ill-conceived political scheme was Col. Burdette, sent to prison in Hanoi, along with two other Thud jocks that day. Ed Burdette died as a captive. His downing made us all a victim because we never got a replacement capable of Wing leader in my tour, but it wouldn’t end there. I’m not sure what finally brought Sky Spot to an end, but a story persists that 355th Wing Commander Col. Giraudo, known for his fire and courageous leadership, refused for that wing to fly Sky Spot. If so, that is another of my reasons for great respect of that man. Those Sky Spot missions were an expediency to continue supporting a con job on the newspapers and ultimately the public, which politically outweighed the lives of our pilots. That political house of cards finally failed but took with it the respect for Vietnam veterans and a good measure of our military’s deserved and excellent reputation, both of which have finally reemerged. And Then There Were None I never heard a bad word spoken of our wing leaders: Col. Ed Burdette, Wing Commander: Col. John Flynn, Wing Vice C.O.: And Col Jim Bean, Deputy for Operations, who was a very experienced fighter pilot. They were fine leaders and courageous combat pilots. They each started flying missions in early October and John Flynn, after his serious damage by AAA, was downed by a Surface to Air Missile on 27 October, the last mission I ever had the pleasure of flying with him. Ed Burdette was downed on 18 November and Jim Bean made it only to 3 January before he, too, was brought down by AAA. That our entire wing staff was lost to us in little more than two months was a serious blow, but the courage with which the squadrons responded to that was a credit to all of our flight crews. There is one defining difference between survival in aerial combat and in our Thud tour. Ground attack is luck based, which is a lot tougher on the psyche. If a pilot did the job to the best of his ability, there was nothing to influence his probability of getting home, except his ability to avoid an accident. One thing about chance is that every occurrence stands on its own. Nothing displayed the lack of associative properties of probabilities, thus the uncertainty of risks, more than our loss of that entire staff within a few months of their arrival. Shortly after I had arrived, Col. Flynn took the big hit from an 85mm AAA battery that allowed him to stand inside the wing for a picture and I’d hoped, but knew better, that gave some security to a very favorite leader. Col. John and that particular Thud, were both tough cookies and continued to fly more missions, but chance has no memory and he was downed and became a P.O.W. on 27 October 1967, less than a month after his first mission. John Flynn endured the terror and pain suffered by a lot of fine and brave American airman in the “Hanoi Hilton”. John has passed on but he will remain in my heart and mind as one of the finest, most courageous, most loyal and honest commanders I ever had, and I had a few great ones, and that’s more than one man deserves in a career. There aren’t many who endear themselves in such a short friendship as John Flynn did. Col. Ed Burdette, a fine officer and brave leader, was lost on a Sky Spot radar mission, a fool’s risk, and it was not he but the planners in Washington who were the fools. The Sky Spot radar control missions were a travesty in practice and they were implemented without principles, as explained. He was shot down before Christmas ’67 and was reported by the NVN to have died in captivity, one of 18 of our courageous countrymen who not just suffered capture, but with it death. Col. James E. Bean, joined the 388th Wing just and was shot down on 3 January 68, only about 4 months into his tour. I had known Jim a long time before when he flew the F-105 in the original TAC operational testing at Eglin, in 1958/59, when I was flying test there. Jim also got home, with the survivors, released in February 1973. That was seven terrible years that John and Jim gave for their country and Col. Burdette, faced the deprivations and finally death. The replacements for our top three wing leaders were more titular than commanding, as far as flying operations, for various reasons. Col. Graham, the replacement for Col. Burdette, was not qualified to fly combat, proved to be a respected officer and a kind man, but died of heart failure soon after joining us. A temporary replacement was flown in from Japan, and was hardly noticeable. I can’t remember him, the duration or even his name. From that point on, we took care of ourselves from the squadron level, because the replacements for our leaders that we got saddled with were neither replacements nor leaders! It was quite some time before we got the last Wing Commander, during my tour. Col. Paul P. Douglas arrived as our new Wing C.O. and I will never forget him, but for all the wrong reasons. He was one of the strangest Air Force officers I ever knew with a cigar almost as large as the man, himself, and he was little in every respect. He was incompetent in the role and downright dangerous flying and never led or even flew on a strike force mission, and I was damned glad of that. After Jim Bean was lost he was replaced by Col. James Stewart, who was a lieutenant in the 1st Group, attached to fly with us in the 27th squadron at Rome, NY. I was delighted to see him and took him on my wing on his first strike mission to the heartland of the enemy. We encountered typical defenses and some added 85 mm AAA on the way home, from the place we called the gunnery school, near Dien Bien Phu. We thought nothing of that, and a bit of jinking protected us from their individual sites. One burst hit in his general vicinity, no real threat, and he overreacted like someone in panic. The sight was surreal and, frankly, when it was over I was laughing, as we flew safely away, because it was such a humorous sight to see his obviously panicked and unusual gyrations while we made gentle turns. Compared to any attack in Pack VI this was incidental. After that first mission, he began selectively choosing missions. It seemed that whenever we had a strike mission to Pack VI he would discover that he had a job that kept him from flying and his antics required last our squadrons last minute rescheduling. I insisted he meet our schedule or fly with the other squadron. Over the years I have received letters from some of our pilots and the comments on both of these “Leaders” have been very disparaging of their performance, capabilities and integrity. What a great let down from the three we started with. I expected there would be some payback on that matter, since Stewart would write my Officer’s Evaluation Report for my entire tour, and there was. I must have been the only combat Squadron Commander in history to receive an Air Force Cross and Silver Star but not an outstanding officer evaluation. It really held no importance to me, because I decided before I volunteered for Vietnam that I would retire soon after returning home, upon reaching 20 years, because he wasn’t the first colonel that I had bucked! There were a couple others, in earlier times. Like those other two, he was smart enough to give me magnificent praise in the prose, but a rating number so low that no promotion board would ever see it. I could not abide any combat pilot who would not try to share the load, and worse yet one who refused to fight, and there were only a few in my two war experiences. Early in my tour I heard a lieutenant colonel in the 44th Wild Weasel Squadron of our wing had quit flying for fear of combat and was being reassigned. My thoughts went back to a young F-86 pilot, second lieutenant, who did that in Japan as we were being readied by the 4th Wing to start our combat tour in Korea. He was the first and only coward I saw there, and I felt prison should have been the least of his punishment. Apparently, here was a guy who lived the good life for 18 years and would likely be allowed to get out of flying duties and continue to retirement. I took that very personally, in light of the young flyers I was responsible for. I requested from Jim Bean that he be transferred to the 34th. I would put him in the back seat of an F model and fly him on my strike missions, until he chose to return to full combat duty or resign his commission. I figured to fly only one mission that way, and get the closest view of Hanoi that anyone but the natives ever had, no matter the risk. I figured he’d resign on just one try, or maybe at briefing. My suggestion didn’t fly nor, I suppose, did the lieutenant colonel, but I hope he somehow never reached collection of retirement benefits. In comparison, I had a young pilot come to me when we were going on almost every mission into Pack VI, who asked to be relieved of flying. He would throw up before each mission and was truly panicked by the threat, but was doing the job. I told him that I would take steps to get him off flying, but dismissed from the service, if that was what he chose. I told him: “You’re a young man with a long life ahead. Think about what I am saying and come back tomorrow with your decision. You have yourself and your wife, and some day children. If you quit now you will look into the mirror every morning when you shave and know for the rest of your life that you are looking at the face of a coward! It’s the same face they will look at. That decision will determine what it is you really can’t stand.” He came back and chose to continue flying combat. A couple of months later I had to assign an experienced F-105 combat pilot to move to 7th Air Force HQ in Saigon, the only such instance during my tour. He was not yet finished his tour, but had flown a fair number of very tough missions and I honestly believe, under his circumstances he displayed courage. I transferred him to Saigon. I had started this tour delighted with the attitudes, professionalism and courage of the top echelon in the 388th Wing, but with three losses in less months the rest of my tour I found that then there were none! In War There Was Hope

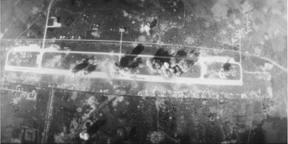

During WW II and from Korea we learned that Bob Hope was synonymous with Christmas to troops at war. That holiday was right around the corner, though things changed little if any during holidays, as even days of the week tended to be a vague concept. Imagine the excitement of troops when we were notified that Bob Hope’s annual Christmas Show would come to us at Korat. Col. Graham, greeted Bob Hope on behalf of the 388th and our Army neighbors. The excitement had peaked with the arrival of the troupe and the show was a great success. We commanders, who were escorts, dined with the entertainers and Bob Hope was very pleasant and enjoyable. The two performers that I especially impressed me were Les Brown who was famous for his Band of Renown and Barbara McNair, the attractive, friendly and unassuming black singer. They were both such unassuming and down to earth people that it was wonderful just to talk with them and be in their presence. On the other hand, I was assigned as personal escort to actress Raquel Welch, who was a pleasure to look at and a pain to listen to, singing or talking. Except for the World’s most famous Aviatrix, who probably earned her right, Raquel was the master of first person pronouns and was well practiced in their use…. I, my, me, myself and mine... flowed from her lips like wine! I wrote to Martha that I tucked Raquel in bed! Actually, while she napped, I sat and talked with her husband and ‘manager’, a nice young guy whom I pitied and she soon divorced. Tactics and Techniques I had never been a member of a tactical squadron that had air-to-ground attack as a mission. A couple flights of dive bombing in my F-5 test program was my only related experience, before training for NVN. Those of us who had a lot of fighter experience got a lot out of our dozen dive bomb training sorties; 48 drops, but wished for more. And I had a big leg up because I started with an excellent ability to achieve dive angle due to an unusual opportunity in flight-testing gained 10 years before. That angle was a primary parameter for accuracy and quite difficult to achieve very accurately. Use of the attitude ball seems feasible, but if that’s what one relied on he was not accurate. The accuracy of bombing has made a quantum leap in recent years. Now the need to dive bomb, at great risk, has passed into history, replaced by electronics and guided gravity bombs that have an error of 10 to 20 feet even when standing off from targets at very high altitudes, and at night and weather. Capabilities not dreamed of in my time. Gravity bombs dropped by the B-17 in WWII had a circular error probable (CEP) of 3,300 feet. Fighter-bombers of that era were pretty good and better if at low speed and low altitude release, but those errors grew with the high speed of jets, necessary as defenses improved. In the Vietnam War, according to an Air Force Association magazine article the CEP was 400. I would judge it at less than half that bad, averaging the experience level, because one bad bomb has a large impact (no pun intended) on error averages. It would be interesting to find out who estimated that figure, because no one outside the base paid attention to our strike films, in almost all cases, and too few folks on the base worked that issue. Furthermore, we didn’t have strike cameras on some aircraft. As I will describe, CEP was a meaningless measure in a large percentage of the more important targets. Considering the defenses we faced in Route Pack VIA, and the number of unqualified flyers, we couldn’t expect excellence, on average. Some who were experienced fighter jocks did very much better than 400, but there were many fighter novices who could not. I noted that problem on my earliest Strike Force missions when I looked at the results of our bombing on the photos from our KA-70 strike cameras. I expected a lot of real bad bombs from the inexperienced but saw far too few really good bombs and was disappointed to see so few bombs on target. I felt that the damage to us by the enemy demanded that we punish them appropriately. Not withstanding the fact that many of the targets seemed unworthy of the loss of one pilot, it was our duty, we would do it, so do it well. Success was surviving the mission for one day, repeated 100 times, and with the rules we faced for that campaign, their could be a lot of rationalizing. We had our hands tied by many shortcomings, but one we certainly could overcome was any lack of determination to improve. It didn’t take Einstein to assess the futility of our efforts there, but that was not germane for professionals. From the first mission, I was amazed we had about an hour total briefing (wing + flight) before every strike force mission, filled with great detail on standard procedures. After 10 missions we knew those facts in our sleep and only had to get the changes of the day. Not for one second did we address the attack, aiming points and the dive bomb run, where the explosives hit the road, so to speak. And we didn’t address results afterwards. We needed commitment to bombing and measure of it! I appointed a Battle Damage Officer and for Commitment adopted a form on which each pilot sketched the target and his planned “sight picture” at bomb release, a 30 second task. This was during an added attack analysis of the mission, just before ending the final brief and departure to the aircraft. The form showed the pilot’s intended sight picture at bomb release, thus was his commitment. I requested one-day service on the first frame from each attacker’s sight film. Since the film started the moment the bomb button was pressed, the first frame showed exactly what the pilot saw in the sight when he dropped his bombs, our measure of his commitment; therefore his measure. Neither was perfect, by far, because both had to assume the pilot was capable of meeting the other critical bombing parameters at moment of bomb release: correct dive angle, release altitude, airspeed and stabilized flight at bomb release, no small task for any pilot, least of all the inexperienced. But from those two indicators, he proved he was concentrating and trying and both those traits assured quantum improvement. I reviewed the results, and posted noteworthy (good or bad) observations with them, on our bulletin board. Having the pressure of our reviews did not make experienced bombers, but would force the effort to try, assuring best results. Visualizing the critical bomb release “picture” gave the best possible chance to hit a target, even for a skilled bomber. In training, I had worked exceedingly hard at visualization and concentration on dive bomb runs, which stuck with me in combat. I learned from my first strike missions that deep concentration nearly eliminated fear during the most hazardous part of our missions. Even the sights and sounds of anti-aircraft bursting near the windshield went unregistered, as if stored in the sub-conscience, to emerge when clear of the target after escape. Accurate delivery of unguided bombs in diving attacks was the most difficult art in flying that I ever tried to master, far exceeding air-to-air gunnery, because of the excessive and large variables. I searched hard for some simplifiers. As a sample, one of many critical requirements was absolutely no variation from a perfectly smooth glide at moment of bomb drop or the result would be like shaking a rifle while trying to hit a target more than a mile away. That is enough of a challenge in level flight, what with gusts, etc. but in the dive bomb run there was need for continuous sharp, often violent and extreme motions to force the airplane quickly to the proper point in space and correct attitude to make a successful bomb run become precise and smooth at the critical split seconds before release. We learned, practiced and were measured from the center of circles, thus CEP and that became the forest in the trees we didn’t see. One thing about our targets stood out, immediately. Many were very long and very narrow: Runways, railroads, bridges, etc. A change in technique could eliminate three of the five major variables which made accuracy so difficult, leaving only the need to glide without control inputs just before release and correcting for crosswind drift as error factors, for those targets. The really tough ones of dive angle, airspeed and altitude were individually difficult and worse, they interacted, but they could be ignored simply with a change in mental approach. By forcing the mind to think of the dive run on such targets, as a landing approach to them, a simple and excellent dive run was possible. There are two ways to make a final approach, first is to crab thus fly straight on the centerline throughout the approach. That would make it absolutely impossible to aim a bomb, which would jump toward the crab wind at release. But the other, which is to drift with the wind, while the airplane axis remains parallel to the centerline, would be perfect. If the airplane is diving so that it will hit somewhere on the centerline, so will the bomb, even drifting free in the same wind when release. All those other factors necessary on a circular target only affect how short or long the bomb travels in relation to the airplane. With a long target, any point on it is a good hit and with 12 strike airplanes probabilities take care of dispersion along the length. It was this last fact that troubled me when we were briefed to hit an exact point on a runway, which returned us to the circular target mentality. All that was left was making no flight control changes just before bomb release. Assuming no control movements at bomb release, only two things demanded attention: 1. Adjust left/right position from centerline (strictly for cross-wind) so as to “float” (dive) to the proper release altitude for the bomb to drift in the wind to the centerline of the target after release, just as the aircraft would in the imaginary landing. 2. Maintain parallel alignment of the x-axis of the airplane with target centerline as the bomb release altitude is approaching, flying with as little control inputs as possible, especially approaching bomb release. At the planned altitude (if in doubt be lower) be extra smooth and release bombs..... Break, pull g’s and get out of there. Whether you were low, high, fast or slow they only affected the bomb by the small difference in sideways drift of the bomb due to longer or shorter fall time, so you hit the target if you were smooth and got 1 and 2 right, guaranteed! I adopted the philosophy that, if you could land on it you can bomb with it! Soon, my time was too full of other duties. It was never practical to get even a majority of our pilots in a briefing, so my hope was that my early interest in strike photos and bombing accuracy would transfer through flight and element leaders. The flight leaders and their pilots lived together, went on R&R together and had time for discussions, hopefully they would often address the subject of accurate bombing, not only the requirement in mission briefs. 5 November: Improvement showed with our efforts, not only in my own attacks, but others’ as well. I was Strike Force Commander to Phuc Yen Airport for a return match with the enemy, on 5 November, just a couple weeks after our first attack there. This time our job was to hit the runway, which had been assigned to the 355th wing on our first strike there. We had made strides in paying more attention to our attacks and the results were evident in our strike photos. At that early stage, I found time to annotate a map with some of my strike mission notes and write home to Martha to share with her some of what we were doing, none of which was classified. That was a practice I quit as a result of the increasing demands on my time. From that mission, I included a series of three strike camera shots of our attack, which I had annotated. I had been pleased, when the KA-70 strike photos confirmed that my six 750’s hit squarely on the very middle of the runway, but more excited about the improving results by the flight. The outcome was far better than before, encouraging me in our efforts to improve weapons delivery.

Before sending the photos I had annotated the first: “Phuc Yen, 5 Nov, I was 1st in, these are my bomb explosions (with arrow)”. The bombs show on that frame at the moment of impact. I also had circled seven 85 mm radar controlled gun positions with a note to the effect. Those are impossible to overlook, because of their geometry, with the radar in the middle of a circle of five or six rapid-fire, long range cannon. The firing repeated around the circle, one shell from each gun, until fire-out of seven rounds each (if my memory serves me). The extremely rapid cycle looked like some kind of a firework circle, though I never noticed guns during an attack, only when watching for them while withdrawing, when defensive jinking was possible ... No use looking for trouble you can’t affect The second photo was great because number two missed by only the width of the runway. Although ‘a miss is as good as a mile’ that was good bombing, far better than in the past, and my element leads bombs all hit dead center a thousand feet down the runway from mine. That frame was annotated with an attack direction arrow and the Note: “These are sites (85’s) at the other end of the runway, of which 10 were identifiable.” Thus there were at least eighty radar-controlled guns in spitting distance from the runway. The third photo added the results of the second of our three flights of bombers and showed that two and maybe three of that flight were also dead-on the runway. Old craters from a 6-bomb string near a long thin structure along the narrowest of the two taxi strips and parallel to the main runway, can be seen from the first Phuc Yen attack. Those were more than 1000 feet right of the runway, showing that the 355th Wing suffered the same problem with bombing accuracy as our wing, since they had done the previous bombing of the runway. One other thing that mission and the photos of the 85 mm sites confirmed, was that the enemy understood Washington and knew that future bombings of this airport would follow the first one in short order. We had 12 SAMs to deal with on that flight and none on the first attack. I made another change in tactics, which I employed leading strike missions, but never tried to promulgate, simply because of the lack of opportunity to train. I did offer the idea to my counterpart in the 469th, Lt. Col. Bill Decker, but his Operations Officer, a product of the Fighter School at Nellis AFB NV, who had flown as my backup for an aerial gunnery demonstration in the World Congress of Flight, was adamantly insistent on tradition. Bill, a wonderful guy made it to one month shy of his 80th birthday, before he passed on after a severe stroke, in May 2002. He is one of so many wonderful memories of an otherwise miserable war. Traditional approach to a target was from 90 degrees off the attack line, then a wide turn while commencing the dive onto a straight line toward the target. The advantages in training were similarity to base leg and turn onto final in a landing approach, but it proved to have great liabilities with extreme defenses over NVN, in part because the turn of a high speed jet aircraft takes much more time and space, than a P-47 Jug of WW II and the lethal defenses. It was obvious that tradition put us in range of SAMs and radar-controlled 85 mm AAA for an extended period. Just one trip on that long base leg at altitude and the extended 90 degree turn on roll-in to dive, all under fire when no evasion was possible was enough to make me open my perspective. The time spent in that diving turn was over a minute for each attacker, and the entire pattern was predictable for the enemy, giving away the target from the leaders roll-in. Multiply that by 16 F-105’s and the enemy was provided time for many more rounds of effective AAA or SAM. We were facing density of defenses, day in and day out, which fighter-bombers had not faced before and procedures from the past seemed flawed under those circumstances. Our ECM formation exaggerated risks because it was widely spread, offered absolutely no latitude for maneuvers, and put everyone but the strike leader in poor position for dive alignment and dive angle. It was no way near the close formation and quick echelon roll-in of the fighter movies about prior wars. Thus it not only adversely affected survival but bombing results, too. We were wide spread, screwing up both dive angle and attack heading for all but the mission lead, both of which decreased accuracy, especially on many of our most critical targets, which I will explain in a bit. I gave it much thought and decided to try an alternative that might provide more latitude. Obviously, the quickest and most direct path into any steep dive is a Split “S”, from level flight: A rapid roll to inverted flight, a high g pull to desired dive angle and a roll-out to upright flight in the dive. That also keeps the airplane aligned with the target’s line, but requires being able to see the target approaching it in level flight for a bombing attack. There was a large concrete runway in the Thailand jungles north of Korat, I expect American made, but unoccupied and without buildings. On a few missions, I had my flights take on a few pounds of extra fuel on our way home to give the idea a trial. I was surprised that with our high altitude at roll-in-to-dive it was practical to come almost straight at the target in the level flight necessary in the ECM formation, and keep target in sight, over the nose, then do a semi-split S directly onto the dive path. Our mission ingress and dives started so high and far from the target. With tries I learned that it only took about 20 degrees off of the attack line in level flight to keep the target in sight until even a 60 degree dive could be attained, and never lose sight of the target. As the angle off of the target line increased to 45 degrees the idea of split S became more of a descending barrel roll, which worked exceptionally well. For example, coming in on an angle from the left side of the attack line required a left half roll while increasing the g to get the desired combination of turn and dive angle to the continue the roll to final alignment and angle, or conversely for approaching a target on the right. That technique proved as easy as a rolling dive down onto the tail of an airplane while getting aligned with its line of flight to run up the rear end. The roll to inverted position proved far easier to accurately align with the target than the conventional approach and to get a steep angle; required for bombing accuracy, plus advantageous for survival. Wingmen could roll in toward the target line and choice of roll out direction (left or right) more easily adjusted alignment and dive angle from the inverted view. Thus wingmen on either side of leader could roll in the best direction for their position toward the target to achieve attack line. Continuing the last half of the 360 roll in the most practical direction took care of final alignment. The pendulum effects of rapid “in and out” corrections were easily avoided. That maneuver gave a better insight to the real dive angle and made easy late corrections that were impractical with the 90-degree entry. Lastly, it eliminated the irrefutable flaw in roll-in from 16 ships in wide spread ECM formation, which influenced succeeding airplanes toward shallow dive. Finally, it began and ended very quickly without warning to the enemy, and required no advisory to wingmen in spread formation, and it was their job to spot the target before roll-in no matter the tactics. When a leader rolled in on a dive run he accelerated so fast, while his wingman waited for his turn that wingmen were on their own from that moment until the attack was completed and the wingmen rejoined, many miles away. The entire force was aware of the initial heading for attack and the actual attach heading, so were ready to then roll toward the attack line as the target passed under their nose in their level flight. Finally, they rolled out onto the dive path in the best direction to be on attack heading. I used it when I led strikes, thereafter, and believe we put more bombs on target and we spent less time getting shot at. Quite frankly, there was a domino effect and if I attacked that way the rest of the formation was forced into the desired response. Sometimes they felt they were too steep, only because they never had been diving with the correct angle before.

19 November:

Ray Vissotzky, one of our most qualified flight commanders, was scheduled to lead our suppression flight, but he switched places with his number three, Sam Morgan, who was nearing end of tour, to give Sam one last lead. Don Hodge was on Morgan’s wing and Ken Mays flew number four on Ray. They elected to protect us from that surface to air missile site, near our target, by direct attack. The missile site was between the target and downtown on our left side and Morgan swung his flight ahead and left to attack it. Almost simultaneously, Ray was hit by a SAM. He tried to make it as far as possible but both hydraulic flight control systems failed in short order, putting his Thud out of control and he had to bail out near Hanoi, where he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, returning home in February 1973, sacrificing more than 6 years of his life in terrible conditions, with cruel captors. Recovery of a downed pilot in that area was out of the question. Ken made it safely home and completed his 100 missions in exemplary fashion. He remembers his brief chase of Ray: “I will never forget chasing Ray Vissotzky out of Hanoi after being hit by a SAM. Looked like an atlas rocket, but he stayed with it hoping to get to the hills, however the controls finally went and he had to punch.” One of our strike Thuds, manned by a 469th squadron pilot, Capt. H. Klinch, was shot down on the bombing attack and we were uncertain how far he got, so I took the flight back for fuel and we searched for him unsuccessfully, along the planned exit corridor. We had to accept that our chances of being rescued on Pack VI missions were zero, unless we could get out to the Gulf of Tonkin, near our ships, or back to the lower route packs of NVN or parts of Laos, but many of those Laos areas were extremely hostile, and should rescue fail the situation could be far worse even than POW, and the same held for Cambodia. I carried a loaded clip and one in the chamber of my Smith & Wesson automatic plus a seven-clip shoulder belt, mostly for those wilder areas. Fifty-six rounds for the bad guys and one for me! It was clear that hands-in-the-air was the best signal for NVN but I felt a fight to the finish was preferable in some other areas. What we learned afterwards of the suffering and hardship, interspersed with tortures and finally slow death of captured folks dragged through the jungles, validated that notion. In my first month I completed 17 missions in 25 days, a big majority in strike formation and was very comfortable with Strike Force command, and looking forward to every mission, not fearlessly, but fervently. That was followed with 13 missions in November, but only 8 on strike force. Then December weather forced us to fly more lower pack missions and I got only 6 of 15 to Pack VI. After that, the number of monthly missions remained fairly steady, however, the tougher and more exciting missions came and went at the whim of weather and Washington. Not only did strike force missions involve hazards, because many F-105’s were lost on individual strike flights, which were the majority of the missions over the seven years of the air war. Strike flights entailed the highest risk per mission, however, resulting in the greatest Thud crew losses, which occurred in 1966 and 1967. Although Rolling Thunder continued long after I left, the number of Strike Force missions was erratic and reduced after my first three months, when I had completed 54 missions. The total number of combat sorties remained high but less were in strike formations and fewer were to Pack VI, so our odds of getting home improved, but with it the excitement declined and the time passed more slowly for me. That is not to say that some of the missions to lower packages were not dangerous and exciting, but after strike forces they just seemed tame. I can’t recall the circumstances of our mission and having bombs over Laos. I remember rolling in from below 10,000 feet, very little to play with in that hill country, because of overcast with very slow speed to allow time to get into the dive and aim. The target was a 37 mm gun position that I couldn’t even see in the jungle. The Forward Air Controller, in a prop driven AD had called for help and the gunfire he had taken was too intense for him to mark the site, but he described the location in detail for me. I met their fire, head-on, all the way through my dive and pull out, until my bombs impacted, dead-on according the FAC, who had asked for help. He was ecstatic because the gun had kept him from his mission. The ground gunners had the advantage in such a scenario, but in this case they failed by a big margin ..... 7 X 750 #s!! |

| previous section | next section |