Chapter 5 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

|

|

|

Chapter 2 Aerial Combat |

|

Chapter 3 Flight Test |

| Chapter

4 Approach to Space |

|

Chapter 5 Limited Weapons, Assured Defeat! |

|

Chapter 6 Limited War: Unlimited Sacrifices & Defeat t/c |

|

Chapter 7 End of the Beginning t/c |

|

Chapter 5 - Limited Weapons, Assured Defeat click on the links below for more of the story... i. Limited Feedback - ii. Back to School - iii. 388 Tactical Fighter Wing - iv. Rolling Thunder - v. Rules by Fools - vi. The Bridge - vii. Good Morning Vietnam! - viii. Home Again |

|||||||||||||||||

Rolling ThunderWhenever weather and Washington permitted, the two Thud wings each flew two strike missions daily. The strike force was usually 16 F-105Ds escorted by two spares to achieve four flights of four to attack a prime target in the industrial heartland of NVN. Usually our number-two flight was assigned to flak suppression around the target by dropping canisters of bomblets, while the other three flights attacked the primary target. The configuration varied according to target for the attack airplanes. There were two configurations for bombing, the most common was six 750 pound bombs on a center mounted multiple ejection rack (MER). The other was a 3000# bombs mounted on each wing on the mid-store station. The aircraft assigned to flak suppression were hung with Cluster Bomb Units (CBU) instead of bombs, which opened at a pre-designated altitude over the gun positions and scattered sub-munitions over a wide area. Strike aircraft also could carry an Electronic Counter Measures pod on each outboard stores racks. The ECM pods interfered with the accuracy with which surface to air missiles could be guided, but at a cost of limited strike aircraft formations and maneuvers, a reasonable trade, as the numbers of ECM pods necessary became available, during my tour. The Gatling cannon was a formidable weapon for defense against attacking Migs or in protecting downed flyers, and we could find some interesting hunting with it from time to time in lower packs, my favorite sport when returning from Pack VI. Our 5th flight had two Wild Weasel (F-105F) two-seaters, each escorted by an F-105D strike wingman, usually carrying CBUs, but capable of carrying Anti-SAM missiles, to be launched under command of the Weasels. The 105F’s were specially equipped to reduce the threat from Surface to Air Missiles, SAM-2, by observing and keeping them in danger whenever their radars showed activity. The back-seater was a specially trained Electronic Countermeasures Officer to locate and identify surface to air missile sites. If the enemy kept tracking us, the Weasel’s missile would track the radar to the source of the SAM control. When appropriate, the flight could visually attack sites directly with the wingmen’s weapons. The latter was frequent in earlier times than mine, even to attack with the 20mm Gatling cannon, however so suicidal that such attacks had generally been reduced to occasional use of cluster bomb drops.

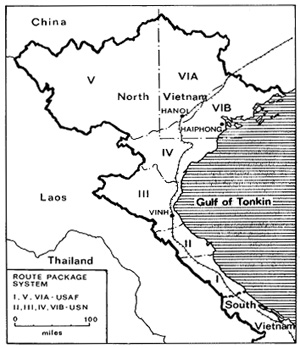

We did our toughest jobs in Route Pack VIA, a designation of a large area surrounding Hanoi and extending to the Chinese border. The map shows the designations of enemy areas of NVN, designated as route packages or “Packs”. By this time, the North Vietnamese had figured out the politics of the war. They had huge numbers of antiaircraft guns and surface to air missiles in prime target area of Pack VI. In fact, some jocks made a red mark instead of a black mark on their Aussie hats (our complement to the flying suit) for each Pack VI mission to acknowledge that fact. Shortly before we arrived, a long-enduring campaign named “Rolling Thunder” was implemented in Washington. North Vietnam was divided into 7 packages. By far, the heaviest defenses were in Pack VI, which was divided in half. Pack VIA included Hanoi and was usually reserved for the Air Force. Pack VIB included Haiphong and was assigned to the Navy. Pack VIA represented the most hostile environment we could be assigned. But even south to Pack I, and north to the Chinese border, the threat of shoot-down was real. The Navy had aircraft carriers and ships offshore of VIB but not of much help when hit in VIA, where recovery of downed crewmen was impossible. More than 396 Thuds were confirmed destroyed or lost to battle damage, some excess of that number being uncertain. The loss locations were: North VNM 285; Laos 57; Thailand 51 and South VN 3. Those in Thailand and SVNM were operational and/or battle damage. More than 60% of the F-105’s were lost in two years, 1966 and ’67. A more vital measure was how F-105 crewmen faired: Pilots shot down and recovered 153; Killed 147; died in Captivity 6; Returned from Missing in Action 4 and POW’s returned; 97. The fact that such a large percentage of pilots survived the loss of so many airplanes, in such a lethal atmosphere, speaks volumes for its durability and toughness, and for the Air Rescue folks. The fact that many downed pilots returned to fly again says a great deal about their skills and everything about the courage and determination of those crews who faced great risks to extract downed flyers. They willingly risked death or capture when there was a chance of saving crews. But the distance was too far and the odds too impossible even for those supermen in much of the area of North Vietnam (NVN). For example, just 3 days before my first mission, Maj. Bob Barnett, of the 469th squadron was shot down which drew lingering attention, because he bailed out in the mountains of NVN, known as Little Thud, very close to the Gulf of Tonkin but also near the heavily populated Haiphong port area. What accentuated his loss was that he was on the emergency radio talking with our guys twice a day as they flew over him enroute to targets around Hanoi. The Navy tried to get to him but a couple of A-1’s were shot up in the process, then, an accented voice took over and tried to coax Navy rescue into a trap, but the decision had been made that the area was impossible to conduct a successful recovery. Bob returned home years later with our other repatriated POW’s. We employed two basic flight paths from Korat to the Pack VI area of North Vietnam, with variations, selections generally dependent on target location and tactical considerations such as target type, attack direction, defenses, etc. Our base was about 15 degrees north latitude, Hanoi is 21 and most strike force targets were between those two and generally between 105 and 107 degrees longitude. Generally, we retraced our path on the way home, and the distances always required aerial refueling in both directions. Our Western Approach route was a north easterly flight from Korat to meet our Tankers for inbound refueling over Northern Thailand, continuing north over Laos to the western border of NVN then going northeasterly to targets near the China border. For the more frequently attacked targets in the Hanoi area we would turn directly east toward the areas surrounding the capital, crossing first the Black, then the Song Lo river which combined to form the very broad Red River that flowed through Hanoi and down the delta to the sea. We could continue east to a small mountain range, nicknamed Thud Ridge, which extended like a finger for about 35 miles southeast from the mountains that blanketed all the areas north to China. Thud Ridge was about a mile high and most vital targets within the Red River delta were within 40 miles of its southern tip, Hanoi being only 25. This allowed for attacking targets all around Hanoi and to the north of the ridge also. The Eastern Approach route, served for the same general target areas, except resulted in attacking from the east or south, rather than the west or north. We departed home to the east crossing the north part of South VN before flying north to tanker rendezvous over the Gulf. Leaving the K-135 tankers we would fly north over water until we passed the port city of Haiphong, turning westerly along Little Thud, another ridge that headed toward Hanoi. Like the western approach, this helped us reduce the threat of SAMs for an extended period. It was a more direct route to many of the towns and targets northeast of the Hanoi. This approach served us well for a number of targets along the rails and roads that connected their primary port of Haiphong with the capital. The Eastern Approach also had an alternate after leaving the tankers. We would turn northwest to the mouth of the Red River and fly parallel to it (northwest) directly to Hanoi. This was excellent for attacking the eastern outskirts of the city, one of the prime targets being their most vital bridge, the Doumer, sometimes referred to as Hanoi Rail and Highway Bridge. A secondary bridge, the Canal des Rapides was just east of the Doumer crossing a side canal of the Red River. All Strike Force missions required refueling to make it to the targets and again to return home, typically about 3 hours of flight, and longer on occasion, especially to provide cover for a rescue, when that was possible after a successful bailout. In route package VI, North from Hanoi, the likelihood of recovery was nil, but strike aircraft would shuttle back and forth from the tankers for as long as necessary. If downed crewmen reached the Gulf or land areas accessible to helicopters in Laos or Route Pack I, we could provide effective support with the 20mm Gatling, shuttling elements to refuel. Not enough can be said of the courage and skills of the rescue crews throughout Vietnam, who were known as the Jolly Green Giants for their camouflaged helicopters. The chopper crews made miraculous saves of airmen. Those rescue guys placed themselves in great risk in the air, and on the ground, under fire to help an injured aviator, sometimes remaining with downed crewmen, when ground fire became too intense for the chopper to withstand.

I flew my first four combat missions from 6 thru 11October 1967, to lower route packs for familiarity and was cleared for Strike Force. These were never more than four ship flights and sometimes merely a 2-ship element. I was on my final attack at low altitude using the gun and pulling out not very high over the target, when my world turned red: Every warning light in the cockpit seemed to light up. My immediate thought was ground fire so I pulled up steeply to gain altitude in case I had to punch out, but found that I had only had an electrical system failure at an inopportune moment. It was a good wake up call, since I had not taken too much stock in the realities of the situation on those early missions, but that was about to change. I was cleared for Strike Force missions and would fly my first the next day. 12 October 1967: When I arrived at Wing in the wee hours of the morning and on through the extensive squadron briefing, I was surprise by the amount of procedures that had to be covered on every flight. Being my first, that was imperative and for a few more to come, but I learned that would not be deviated from even with four veterans in the squadron briefing, done at a flight level. Our force would attack the railroad at Bac Ninh, about 15 miles from Hanoi, on the northwest rail lines. We would fly the eastern approach to Little Thud. The entire force taxied out, with the Weasel flight first. The flight leaders would level off and pull back to minimum afterburner, to maintain it as a beacon for wingmen to locate him and join up, especially vital before dawn and when the visibility was poor. As we cruised by flights toward our rendezvous with the KC-135 tankers I was overcome with drowsiness as the sun began to rise and struggled to remain awake. That was disturbing and uncomfortable in one respect, but a happy experience in another, in realizing that I was not afraid of what lie ahead. If that wasn’t the cause then my brain was doing a great job of keeping me from reality. I had wondered, from the moment I volunteered for this tour, how I would react to the risks that we all were fully aware of from the loss statistics and reports of the defenses. The dangers to the Thud pilots were well advertised throughout the Air Force. We were especially pleased that F-4 pilots, who escorted us to the edge of the SAM zones, paid us the honor of declaring we had “Balls of Brass.” At least we thought it a compliment. The realization that I was fully prepared was one of the most satisfying experiences of my life, and I saw enough of that threat on this mission to test me. By the time we were on the tankers, drowsiness had departed. I had no trouble concentrating on the job at hand from the moment the mission commander started his roll-in on the bomb run and throughout my attack, the result of working so hard at visualization and concentration in my dive bomb training. Immediately I discovered that nothing reduced the stress of a mission more than deep concentration on a successful diving attack, something I realized could help our young or inexperienced guys. Only after the bombs released was I free to evade defenses and there was no remaining obligation except to find my flight. The ability to maneuver and evade fire increased the feeling of security, from that moment. I had not only noticed but marveled at the flak until it came near my time to roll-in, but became oblivious to it the moment it was my turn to dive into the attack. I found that to be the case on every mission, except when bursts happened right in front of the windshield and even then it was not really distracting, but sort of got stored in memory to recall after clearing out of the high threats. I realized then, that there would never be a strike mission that was not greeted with anti-aircraft artillery, AAA, and in Pack VIA a hell of a lot of it. Frequently the missions were spiced up with volleys of surface to air missiles (SAM-2), which were most lethal of all but due to quantity, second in danger to the AAA, in my personal impressions, though others disagree. The Mig-21 fighter jets added the third threat to the enemy’s arsenal, and could never be ignored, although my 100 prior air combat missions tended to minimize them in my mind. But all three accounted for a lot of guys not getting home on time or ever. The AAA went from radar assisted 100 mm and 85 mm, capable of hitting us at any altitude we normally flew missions, 57 mm fully effective shortly after our roll-in and 37mm added below 10,000. The Russian ZPU, a rapid-fire machine gun could track us well, even at high speed during pullout. I never really noticed to ZPU in the high threat areas, but I was able to watch them after I pulled off strafing targets at low altitude on my way home from Hanoi, and that weapon was able to effectively track when flying at 500 knots, even when evading by pulling heavy g’s. The F-105 had a gun-sight camera, which was initiated by either the gun trigger, or the bomb release button, the latter for only a brief period to display the bomb release aim. And we sometimes had a 70 millimeter camera mounted under the belly which was also initiated with bomb release and took large definitive still photos with a prism system that moved fore and aft to scan along the flight path, thus providing good coverage of battle damage and on occasions some very unexpected pictures. The films would record bomb impacts, though not always correlated to individual results. An advantage to the NVN defenders was the two wings arrived on target at consistent times twice daily, and often to the same target in sequence, about 30 minutes apart. When the weather and politics were right, meaning two strike flights daily, the NVN could count on the former and be ready in case of the latter. Additionally, our refueling activity, limited egress paths and the NVN radar and radio monitors helped their anticipation of our attack area and visual contact took care of the rest, well in time for full response, wherever we struck them. Add to that the limited number of compressed site areas and the defenses held a lot of Aces in their deck.

13 October:

Roscoe was so important to our morale that he deserves an appropriate introduction. His historical info I gleaned from notes of a “Roscoe Control Officer” who was assigned shortly after Roscoe was separated from his master and adopted by the wing. I got to know Roscoe better than most and I can say without fear of contradiction that it was Roscoe who was the “Officer Control Dog!” I consider dogs a greatest companion for mankind and it took me no time to put Roscoe in the top of my list of best friends at Korat. He had arrived there in June of 1966, with his owner, Maj. Ray Lewis when the 34th was formed, his method of transportation being the only uncertainty. His master Major M. Ray Lewis was shot down on 20 July over the Northeast Railroad near the border of China. Ray named Roscoe in memory of his own best friend, Capt. Roscoe Anderson, killed in an F-105 accident. Roscoe nearly died of a broken heart for quite a while, after Ray Lewis did not return to him. Some say he was a Japanese dog, others that he came from America. He was probably the only dog I’ve known who had the same Flight Surgeon for his check-ups and medications as the flight crews. When I arrived he was the companion of all but best friend of none, 16 months after the loss of his master. I made great effort to overcome his grief with him and he got especially close to me, which gave me great joy, until I returned home. Afterwards I worried that I had just created another opportunity to feel that those he attached himself to with love, would always desert him. I even tamed a stray Thai dog, I candidly named Uggy, hoping for companionship for Roscoe, but mere acceptance was Roscoe’s limit. Late in my tour our new and enigmatic Wing Commander, Col. Paul P. Douglas, would call me aside and say we were going to have to put the dogs down, as they were potential health hazards. I told him he would face a real mutiny, and it wouldn’t have taken much smarts to realize that I would have been the instigator. After I left for home, I not only missed my buddy, Roscoe, but I worried for years whether the loss of yet another best buddy would set him back again. I was pleased to recently read of his extended life. Although he had heartworms, for which he was treated and became a bit overweight he was doing well in May 1973. He had hung on to complete his job until the battles were over!

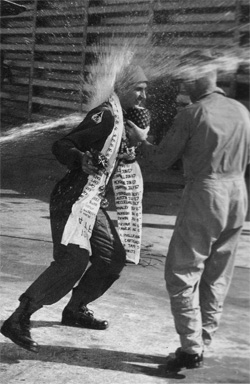

There were very bright sides to my tour, not the least of which was celebrating “100 Mission” Ceremonies, with those fortunate to be going home. I am repeatedly reminded of one, in living motion, that was our celebration of end of tour with Dave Waldrop. It wasn’t any more special than all the others, in spite of Dave’s two Mig kills, and the water being sprayed was no wetter. I never realized until recently that Dave was so astute that he maneuvered my butt toward the camera the entire time he was filmed and sprayed, with that damned big smile, which allows the troops from the 34th to exclaim as they see us (as I do repetitively on a TV segment of Discovery Flight about Dave’s feats): “Why that’s Dave Waldrop, the Mig killer! I flew with him ... and that Asshole facing us, too! That morning, when we arrived for the wing briefing, we were greeted with a handwritten chart on the briefing screen that welcomed our arrival and declared: “KEP Friday the 13th …Y.G.B.S.M!” YGBSM was our expletive, “You’ve Gotta Be Shitting Me!” reserved to be uttered only when the demands from Headquarters were unbelievable. Under that usage guideline, the target selections and the rules of engagement, it seemed that most everything that came down from Washington through 7th Air Force headquarters demanded its use! Kep was one of two primary airports of the NVN used by the Migs. I think that they had never been attacked and were known to have unusually heavy defenses, even for an area where all major targets were well defended. I was really psyched up about bombing the airport runway about 34 miles northeast of Hanoi, on North Vietnam’s major road (1A) and railroad line connecting with China. The next best thing to shooting an enemy’s airplanes out of the sky would be blasting them on the ground. We would take the eastern approach. The Little Thud variation was ideal for Kep, avoiding the Hanoi city defenses in route. That target alone would have more than enough SAM and AAA to make life exciting, and possible brief. This mission was a big event for me, and I got a good dive pass and bombs on the runway, but in reviewing the strike films from our KA-70 belly mounted strike cameras, there were too few who hit the runway. Dive bombing was the most difficult skill for a fighter pilot to acquire, and we had too few with the necessary experience, and we could improve that, I thought. But one thing we couldn’t improve was that 750# bombs made such small divots on a runway that they were hard to detect after the smoke cleared, unless sun angle formed a shadow. Our only other available bombs were 3000 pounders, which had mostly explosives in a thin casing, thus had no penetrating capability. The big bomb was great for structures.

The results on that early mission drew my attention to lack of interest in the photo results. In my prior air combat fighting Mig-15’s checking results was the first order of business after landing, I must confess to those who had hit a Mig. Vietnam war attitudes were induced by the political nature of the war, where bomb tonnage delivered was the political measure of success in Washington, not battle damage. It also got me to thinking about the lack of any attention to the most vital accomplishment of our job, the dive-bomb attack. To the contrary, the wing’s briefing officer had assigned individual flights a specific aim point on the runway, a bad idea for best bombing results on runway, being very long and narrow. As a result I brought home a notion to try to do something to improve our squadron’s bombing accuracy. 15 October:

After a day off, I was again on a strike

force mission, flying number four, with 750#

bombs. Had it not been hazardous for people on the ground, I would have landed with the load to drive home the point. Instead, after all the others had landed, I made a very obvious low and slow pass down the runway, just for show, then went away and made a safe salvo at the approved area. I knew it would get the attention of a lot of jocks when a returning Thud passed over with a full bomb load, making a more impressive statement than I was about to deliver. At the Wing debrief I was still mad as hell and made comments in no uncertain words that what we did was inexcusable for guys who hang it on the line, over tough targets, to be defeated by a few assholes who couldn’t whip our butts if they outnumbered us. Unless we were under attack, personally, I hoped to never see such a disgraceful display or be part of such shame ever again. At this point we were flying strike force with pilots mixed between the 34th and our sister squadron, the 469th . I felt some regret for my outburst as I began to see our guys doing the tough stuff without a whimper, but we couldn’t let the Migs force us to abort entire missions, by threat, even though it was real and a constant danger. 17 October: I would fly my 8th combat mission in 12 days and it proved to be one of the greatest eye openers of my flying career. A wakeup call for a morning flight and my entire tour of combat. More than any other it affected my view of what I was there for in a very positive way, because I was not only the commander but at age 39, an “old man” of the squadron and had a job to comfort and encourage as well as set an example and lead. We arrived for the Wing briefing to find out this would be a tough day, but that was the ordinary. The target was announced to be Dap Cau railroad yards, located along the Song Cau river, near the larger city of Bac Ninh. That terminal was on the northwest line out of Hanoi, about 20 miles northeast of the capitol along a main highway (1A) and NVN’s prime railroad tracks, northeast to China. The area was a hub of activities and therefore a defensive center for the enemy, as well. We were aware of severe defenses surrounding the entire Hanoi area and expected the threats to be heavy whenever we attacked in the area. The defenses didn’t affect our strait line of ingress because they were so heavily deployed that it was impractical to consider their geometry. The completed defense in all these surroundings offered changing threats with Mig-21’s hitting first, under ground radar control, usually diving in from above and firing Russian Atoll Missiles, infra-red guided, with both proximity and direct hit fuses. These copies of our Sidewinder were effective and lethal. As we penetrated the broad areas of SA-2 Surface to Air Missiles (SAM), the Migs typically stood off, leaving the next line of defense to this white, flying telephone pole, ground radar-guided with a powerful nose explosive that could be detonated either by a pre-selection of proximate fuse or ground command. Use of SAMs in terms of quantities was unpredictable, probably due to foreign supplies and logistics, but they were sometimes fired in large numbers. On this mission we had only two SAMs fired. I stated that my personal opinion held AAA to be our deadliest of the three major threats to us, which is very argumentative statistically, but that mindset may have resulted from what was about to occur. I have seen the WW II reports and pictures over Berlin, etc. with B-17 attacks and I would guess that the density of fire we faced at VIA target areas often exceeded that, if for no other reason than we numbered 16, tightly grouped, compared to hundreds of bombers broadly spread. NVN defenses could be constrained to maybe a dozen prime target areas, and the heartland of Hanoi, their grandest, was only about 5 miles in diameter. Add to that the assurance that the times we would arrive, twice every day, was about a 30-minute window, and when one wing came, the other would often follow. Planners were not stupid, it was just that our ability for two F-105 Wings to each fly two maximum capability daylight missions, averaging about 3 hours, defined our schedule quite precisely for the enemy, because a portion of our airplanes had to be used on both sorties. We had smaller size missions also flying daily, weather permitting. Turn around with full combat loads is not only tough work, but takes a good deal of time. I was flying tail-end Charlie, number 4 in the 4th flight, thus be the last to roll in on the attack, so I would get a good view of all the others in their dives. Some believed the rear slots were more vulnerable, which is argumentative when there is enough anti-aircraft fire for everyone. I never felt it mattered where I was in the formation, when the dice were rolling, they didn’t stop by tail number or flight position. We arrived at the tankers, this time over northern Laos, and took on full fuel in standard order of flight leader, 2, 3, then 4. The sequence assured the positions that used more fuel would depart for targets with the most. Each flight had its tanker and we flew formation with tankers in a racetrack pattern, until time to top off the fuel and depart for the target. The initial refueling of four took some time but the top off was brief, which assured maximum fuel for each and minimum variation within the flight. We flew north to about 20 degrees 45 minutes north latitude, then eastward into North Vietnam passing Dien Bien Phu, where the French had been badly defeated by the NVN. This was always a point for alertness, since the NVN had radar controlled 100 mm or 85s batteries scattered about and sometimes practiced on us in that vicinity. The entire country north is mountainous and rugged and up to a mile high, so visually acquiring them was impossible. We cruised east in spread formation for Mig watch to Thud Ridge, and there were warnings of Mig activity but no attack. Then tightened to formation flying southeast along the ridge to gain protection from SAMs, until about 20 miles north of “Downtown”. From there we turned eastward and assumed ECM formation for the cruise to target, climbing to over 16,000 feet for our attack. I got my first full view of Hanoi and its’ surroundings and of how large the Red River was and the great expanse of the huge delta going south of Hanoi. Now the primary threat of Migs would be replaced first with the Surface to Air Missiles. The SA-2 missiles that were steered toward us by two operators, ‘flying’ the bird, a dot on a line, elevation or direction. The ECM simply made the line wide enough to increase the chance of missing. The ECM formation turned us into a larger box in space on the radar. The enemy could guide their supersonic SAMs through our formation with a pre-launch choice only, for proximity fuse setting or ground command. This game of “chicken” we played, was very good, but not perfect. The rapidly speeding white missiles would pass among us, either exploding within the formation by ground command, or if on proximity fuse to pass directly up and safely through us, unless it sensed a nearby Thud and exploded, a deadly event of chance. Earlier in the war, when my friend Howard Leaf was in the 357th squadron, 355th Wing at Tahkli, and before ECM pod’s were available, the Thuds flew into the target area depending entirely on warnings from the same crude gear we still used to signal a near-by launch. They flew in closer formation and visually searched for flying SAMs, when warned. Then dove toward them and finally broke at the proper time, like avoiding a fighter attack. If timed correctly, the high-speed, missiles could not make the turn. That was a pretty good defense, with one really big issue: “IF you got a warning AND saw the missile in time?” If you didn’t see the SAM it could be deadly! This option was still used by us, when flying in four ship flights, including the Wild Weasel missions, where pods were not used because they defeated the Weasel’s own detection gear. I liked the freedom offered to all the pilots by ECM to pay attention to the target and be able to mentally prepare for the roll-in, which varied greatly, depending on the character of the approach, its angle to target line, and the roll in point. Assessing and mentally preparing for those factors had a lot of bearing on the accuracy of the bomb delivery, our primary job! As we started a left turn I had a great view of Hanoi, the expansive Red River delta and very broad river. The delta had many rivers, one of which meandered past Bac Ninh, 20 miles east as we turned. We departed the ridge at about 12,000 feet, hit the burners and leveled at about 18,000 for the dive runs. The radar aimed 85 or 100 mm batteries, opened up with their large black burst around us as we approached. They posed a real threat, being lethal well above 20,000 feet. The target was to our right so I was sitting on the far left and above the last seven to make the turning roll-in to the dive before me. As the lead flights went into full dive one by one, I began to see the black bursts of the long range AAA. Then, as the lead flight started down, the smaller black puffs of 57 mm and finally the grayish puffs of 37s as the dives extended. Number four on the 3rd flight had rolled into his dive, so my leader would follow suit momentarily, but I was watching the diving line of attackers when an airplane from the attacking flight was blown to bits, then another was destroyed and almost simultaneously a third....three of my new squadron mates would not come home. It was a picture that was indelible yet momentary. Suddenly my element lead rolled in and it was my turn. Now I had only one thought and that was to place my 6 bombs on the railroad. With a rail yard’s vulnerability and a careful effort, I knew I could place my entire load on target. When I rolled in for my dive bomb run I was completely focused and what I saw was out of mind: The best catharsis for fear on a dive bomb run and absolutely necessary to bombing accuracy. My intended 60 degree dive would be shallow, due to starting from the farthest outside of the formation, but I could adjust for it with a lower bomb release, faster speed and/or aim long. Fortunately, the railroads tracks were long and straight so only the cross-track miss distance was critical, a far easier situation. After release of ordnance I was free to make any break, keeping in mind the withdrawal direction to locate and rejoin my flight. We fueled in fours on our assigned tanker, inbound and out, but this time we arrived as five, because Capt. Floyd “Skeets” Heinzig, the only flyer left in the air from the 3rd flight, joined us on our journey home. His moving in to join us really drove home the realization of what I witnessed, and I suddenly recalled the deadly reality of those black and white bursts around us all. As I flew home and contemplated what I saw, it occurred to me that I still had 92 missions to fly and that there was nothing I could do that would change the outcome of my efforts, except bomb well. I may have become somewhat a fatalist at that moment. And I don’t remember ever being truly afraid on a mission, as I had long before at age 22 when 4 Migs seemed to have me cold turkey, alone and defenseless. There were periods of uncertainty or ominous feelings, sometimes before a mission, but never for long --- you could not allow that to survive in flying. I also attribute some of my demeanor to my family being more self-sufficient than in my days of Korean combat, and equity in death benefits for all this time. I thought I saw three separate hits for the disaster, and another observer felt the third was the result of one impacting the wreckage of another. The three downed pilots, all from the 34th squadron, were Tony Andrews, “Digger” O’Dell and Dwight Sullivan. Even a single survival seemed unlikely to me, with my view from the eagle’s nest, when all three went down. The loss of three of our comrades together was obviously a shock to all, but with 114 crewmen down in 1966 and us rapidly approaching the 109 total downed in ’67, our pilots were conditioned to losses, when the hottest targets were being hit twice daily and good weather assured that. My introduction to the threat level was swift and thorough. Only a period of very bad weather in December kept us from suffering far greater losses that year. My roommate Lt. Col. Rufus Dye was assigned to wing headquarters, working for Merv Taylor in the operations compound, a secure area where mission planning, wing briefings and intelligence matters were conducted. We were together on a strike mission, inbound, and Rufus was in the flight directly ahead of me when we got a warning that Mig-21’s were approaching and the next thing I knew an Atoll sped just below me and impacted his aft section, with quite an explosion. Rufe’s Thud was badly damaged and mission lead sent one of the guys to escort him out and we continued east to Thud Ridge, then to our target. The Mig had dived down from high altitude at supersonic speed and climbed out of harms way before F-4’s could intercept.

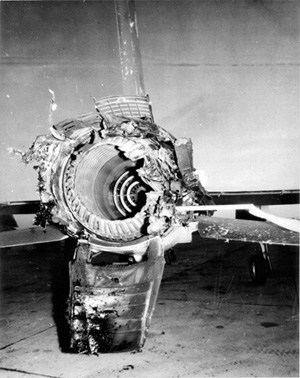

Although his whole aft section was devastated, and a segment of the missile lodged in it, he got home. It had not damaged the critical flight control single point failure right below the rudder, almost a miracle in that part of the airplane. But, his power loss was so great that the KC-135 had to reduce power to idle and dive for speed, while Rufus used full power to refuel to the extent necessary to return safely home. Looking at the photo of his aircraft, most vividly impaled by the missile’s tail in his own and with the entire afterburner and tailpipe in shreds, it is difficult to comprehend how he made it.

Those big Texaco’s on a wing, the KC-135s, were always there when we needed them and would move northward in peril, whenever called upon, as they did that day to save my roommate, Rufus Dye. And talk about skills, the boom operators were so practiced that we could relax when attached and sucking the JP-4 fuel. They never flinched and no matter how fast we decelerated in our approach to join, they stuck it to us, with their fuel probe. There was a great mutual trust and respect between pilots and “Boomers”, who were great formation flyers in their own right.

Little more than a month later, our squadron mate Doug Beyer and his Thud (#512) made it home, with damage similar to Rufe’s, again the victim of a rear attack with another infrared guided missile fired by a Mig-21. It looks like Doug was fortunate to have the missile explode a little further from his aircraft, but again in an area where catastrophic loss of control was likely.

This is Doug Beyer’s personal recollection of that mission:

“Early on the morning of 12 Dec 67, we went

through the normal mission briefings. Sam

Armstrong, Irv Levine and I were three

members of the flight. My memory fades on

the fourth. Target was Kep Airfield,

northeast of Hanoi. We went the water

route, hit the tankers, and entered the area

south of Haiphong. The weather was solid,

and we were in and out of the clouds the

whole time. The Weasel flight kept us

advised as to what they found—no breaks,

anywhere.

He met me at Base Ops, and handed me a

rolleron that they had gotten out of the

rear of my engine area. It had no serial

numbers on it, so I assumed it had to be

from an Atoll missile. One of the oldest

master sergeants I’ve ever seen explained

that the US had quit numbering the rollerons

as well, and he was certain the rolleron was

from a Sidewinder. Interesting. Gary Durkee, now deceased, reminded me he inherited 512 after it came back from DaNang. Said it nearly killed him several times with in-flight emergencies. I wonder where it is now—in the bone yard in Tucson, maybe”. Spence Armstrong was on that mission too, and I asked for his recollections. His reference to “Takhli” was the full strike force from the 355th Wing based there. This recollection also shows how the more seasoned veterans, like Sam Morgan, helped us acclimate by getting on the wing of new guys, Spence in that instance. “On this mission, my log shows that the target was Kep Airfield. I lost my DC generator on the tanker and had to turn off my navigation equipment. Don Revers, Pistol Lead, lost his AC generator so Pistol #4, Sam Morgan wound up as mission commander. Bob Elliot was #2 and I was #3. Takhli weather aborted 5 minutes ahead of us and we did also a minute later so there were all sorts of Thuds in a small airspace. Half way through the 180, we were jumped by Mig-21’s. They fired heat seekers—one hit Doug Beyer who was Hatchet #4. He landed safely at Danang. My comment in my log was that this was a fiasco and we should never have been sent up in that weather condition. Within a few months our third squadron mate would feel the blast of an Atoll missile under surprise attack from on high. The Mig-21s had great advantage with help from their ground radar control to surprise us. Then dive at supersonic speed from well above us and behind, completely out of view, and fire their air-to-air infrared guided missiles up our tails without warning. On 4 February, that happened to one of the 34th squadrons finest young pilots, who had been with us just a short time. Captain Carl Lassiter had already made his mark and I had noted that he would undoubtedly become a flight commander and strike force commander. He was an experienced fighter pilot with excellent flying skills, leader attitude, courage and confidence. Coming home from a mission, I had challenged him at formation acrobatics and he was excellent, both leading and flying wing. Carl’s fate is recalled by Monty Pharmer, who later became a flight leader: “My special friend Gary Durkee and I were in separate flights. I was with Bill Thomas and two others. Gary’s flight included Carl Lassiter. Carl had more missions and we respected him as one of the “Old Heads”. We all had breakfast together.....it was raining and still dark when we got to our planes. The mission was uneventful into Laos. We crossed into North Vietnam in the vicinity of Dien Bien Phu, the battlefield of the French downfall. The weather ahead looked bad with a solid overcast and a lower cloud deck that could preclude us from descending into the target area. About that time our F-4 flight cover started calling out Migs at our rear. No sooner had they called than Carl reported that he had been hit by an air-to-air missile.... he was ejecting. He had a good chute as he drifted down into NVN. The F-4s pursued the Migs and got a hit on one. The mission was cancelled due to weather and we weren’t too disappointed about that. It was a shame that Carl was down and the mission was never accomplished. The one good bit of news we received almost immediately from our excellent intelligence was that the Mig that shot Carl down had been hit and had crashed on landing at Yen Bai-the pilot was killed-he had been one of the NVN “aces”-their best. Carl was captured and spent the next 5½ years as a P.O.W.” I had envisioned so many great missions lead by Carl that it really was a blow to lose him. This loss was hard to take, as were the loss of any of our pilots, but the fact that Carl went down on a mission that could not be finished because of weather added even more to the despair with the fruitlessness of the contest that we were placed in. I wouldn’t have traded that tour, but that was because of the comrades and the personal challenges, not the outcomes or impact on the enemy. SecDef McNamara and President Johnson would turn us off in good weather with their game of political war management and demand we fly in terrible weather when they had the green light on, simply for higher bomb tonnage reports to the media. 24 October: I flew on both Strike Force missions to Pack VIA my 13th and 14th missions. That was a long day, with the wake up at 1:00 am and the last debrief after dark; total flying time was over 6 hours. It entailed a lot of briefing and debriefing time. The little water I carried on missions was reserved in event I was shot down, and dehydration accentuated being very tired at the end of that day. The afternoon mission that day was the first strike on Phuc Yen Airport, with Strike Force take-off at 1400 hours (2 p.m.). We expected and got a lot of action from the defenses this time since NVN had become aware of how Washington played the game. We had recently hit Kep airport, and that signaled open season on their other major Mig base. Our bombing results were good with 3 very large explosions and 5 Migs destroyed. Not too long before this mission I made my attack on a target during which there were more flak bursts nearby than any other mission. I mean one 85 blew right in front of my windscreen. More was bursting close in front during the entire dive and yet I got home to my surprise with no hits on my airplane. But on this mission there was the usual heavy flak but I didn’t notice any extremely close. After landing, when I was in the dining room, my crew chief came in with some pieces of shrapnel he had dug from the airplane, and said they had more to remove. I recall that because a small piece of it graces a nifty little plaque with a Thud and the annotation: “To: Lt. Col. Robert W. Smith Presented by Ho Chi Minh: First Phuc Yen Raid, 24 October 1967. My second flight that day was my favorite target, their finest bridge and that mission is discussed later, with a collection of attacks on that structure. Mission recollections are not equivalent, even between lead and flight members. The sights, sounds and experiences of the pilots of a strike force can be so varied, since much happens over a pretty broad space and so damned fast. That space seemed to shrink when the SAMs were many and the flak got thick, as the roll in for the dive run began. But even then the observations were so different between the guy who saw the flak burst right in his face on the dive and one who heard it and another who felt unscathed, but sometimes brought home shrapnel, all from the same flight, in the same dive run! The spacing on the roll in translate into miles of separation with the great acceleration in the beginning of a diving attack. Spence Armstrong, recalls a couple of his missions in this same period. As a case in point, the first is his recall of the same one that I just described: “On 24 October, my 11th mission, we struck Phuc Yen Airfield. This was their primary Mig 21 base just Northwest of Hanoi. Up to this point it had been off limits for attack. We never did strike the civil airfield (Gia Lam) outside Hanoi although it was widely known that Migs sometimes used it. LBJ and McNamara had this dumb idea that we would gradually increase the targets we were willing to strike and this was the way to get the North Vietnamese to sue for peace. Our wing came in first using the land route and dropped CBU’s along the flight line to hit the Migs in their revetments. Takhli rolled in just behind us with 3,000# bombs to destroy the runway. The F-4C’s followed them with bombs and maybe even the Navy got in on this historic attack. I think we surprised them and did some considerable damage. There were no U.S. losses. No SA-2s were fired and the 85mm flak was spotty. I was written up for a Silver Star on this mission but it was downgraded to a Distinguished Flying Cross. This was the first of three Silver Star downgrades—so I never got one although many Thud pilots did. “The next day we went back to Phuc Yen. That time, we were attacked on the way in, by Migs. Our flight punched off our bombs and tanks and broke into the Migs. I suspect they abandoned their attack when we filled their windscreens with bombs and tanks. Anyhow, the rest of the flights got to the target safely. The next day I carried 3,000# bombs for the first time and was impressed how much sleeker the F-105 was with this load as opposed to the 750# bombs carried on the centerline. The target, Hu Gia between Thai Nyugen and Hanoi, was clearly under the clouds so the mission commander wisely directed us to hit the part of the rail line that was clear and we did so nicely. Two SA-2’s were fired without effect.” I was unaware for more than 30 years that Spence never received full recognition of his contributions and valor. He was submitted more than once and I had expected that that submittals were usually approved at 7th Air Force, and I damned well knew they were deserved. My confidence in the approval process was high because the difficulty and risks of the F-105 combat tour were well known throughout the 7th Air Force and personnel offices up to the Pentagon. Spence proved his valor to those he cared most about, his peers in combat. He proved his leadership to the Air Force reflected in his selection to the rank of Lt. General! |

| previous section | next section |

.jpg)