Chapter 5 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

|

|

|

Chapter 2 Aerial Combat |

|

Chapter 3 Flight Test |

| Chapter

4 Approach to Space |

|

Chapter 5 Limited Weapons, Assured Defeat! |

|

Chapter 6 Limited War: Unlimited Sacrifices & Defeat t/c |

|

Chapter 7 End of the Beginning t/c |

|

Chapter 5 - Limited Weapons, Assured Defeat click on the links below for more of the story... i. Limited Feedback - ii. Back to School - iii. 388 Tactical Fighter Wing - iv. Rolling Thunder - v. Rules by Fools - vi. The Bridge - vii. Good Morning Vietnam! - viii. Home Again |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

388th Tactical Fighter Wing388th Tactical Ftr. Wing, 34th Squadron, Korat Thailand, 7/5/67 to 4/22/68

“We Are Going Downtown Today, working the railroad ----- bridge northeast of Hanoi. 0230 briefing. 7th Air Force Saigon issued target orders the previous afternoon: target, route, flack and SAM *1 locations, tanker rendezvous, air rescue orbit locations, fighter escort coordination, electronic countermeasures. Twenty-two aircraft will leave the Thailand base: sixteen bomb carrying strike craft (F-105s, Thunderchiefs and two spares, four SAM suppression craft (Wild Weasels). Eight air-to-air fighters (F-4, Phantoms) for Mig protection will join us at the tanker rendezvous. Primary target: Hanoi vicinity. Weather at target; marginally acceptable. Weather in refueling area; fair. Intelligence briefs the target: aiming point middle steel girder span, fifteen degrees cross approach, four SAM batteries in range plus heavy 37, 57 and 100 mm flak. Expect Mig 19s and 21s.

We lost two thuds yesterday on a target two miles from this target. We average seven losses a month. “There ain’t no way. Why me? I’m golden! There’ll be snakes in the grass in banana valley today! After all, it is a counter!!!” The commander briefs the flight. Take off Weasels first, then Omaha, Ozark, Gunsmoke and Winchester. Spares last. Five seconds between aircraft, ten seconds between flights. Because of the fog and drizzle, we may have to stroke the burners during climb for a visual. Follow radar vectors to the tankers. Hook up rapidly and try to get a second top-off prior to drop-off point. We’ll leave the North station, then Black River at the hook. Direct to the loop on red River, direct to Thud Ridge. Southeast along Thud to the northeast railroad. Right turn to face the Mig airfield, as we come off target. Rejoin in flight and egress northwest over Thud Ridge. Expect Migs and SAMs inbound, with intense flak at the target, the same outbound. Post strike refueling at points indicated. Take on 3000 pounds and head home. Personal Equipment Shop. Zip on the G-suit and survival vest with emergency radio and 38 attached. Pick up the chute with beeper. Replace the bail-out oxygen bottle with a small machete. Grab two pint plastic bottles of fresh water and head for the crew truck. Fog and drizzle ___ everything wet. Up the fourteen foot ladder to the cockpit, strap in and signal to the chief for power. Hit the shotgun start: tumble, smoke and RPM. Quick systems check: electronics, radios, IFF, radar, nav system and gun sight __”Let’s taxi” Rolling out of the revetment, I reach up next to the windshield for my clipboard and strap it on my right leg. The drizzle has made most of the mission card illegible. “Tower to Omaha Flight: cleared on and off.” Run ‘em up light the burners, release the brakes, hit the water alcohol switch. Rolling, and airborne at 196 knots. Good launch: twenty-two birds off in less than two minutes. Good join-up in flights of four, with only a couple of ‘stroke-the-burner’ calls. On top at 16,000 feet headed for the air refueling area. Lots of help getting to Red Anchor orbit point with ground radar control, airborne radar and forty-four eyeballs. Tanker join-up, routine. Enough daylight at 16,000, and we are mostly out of the clouds, with just a few small bumpers here and there. The Weasels check in on the tankers: the Phantoms arrive. “Omaha to Tanker Lead: drop us off at nineteen degrees north.” Headed three six zero toward North Station. “Ozark four to Lead: primary hydraulic system out.” “Spare One: Fill in for Ozark Four. Spare Two: Escort Ozark Four home.” Passed North Station, turning fifteen degrees to the Black River. As we steer right another twenty degrees for the Red, the Weasels are twenty miles in front snooping for SAM indications and checking weather. We cross the Red River, headed for Thud Ridge. “Bandits! Bullseye northwest two angels.” The Migs will play today. Phantoms move overhead toward the Mig intercept. Increase run-in speed from 480 to 520 at the northwest end of Thud. “Weasel to Omaha: SAM indications at 11, 12 and 2 o’clock. The one at 2 looks like a launch.”- - - - “Launch! Launch! Let’s take it down.” Weasel Two’s mike button is stuck open for five seconds and we can hear the heavy breathing. Everything seems to be in order: Weasels attacking the SAM sites, Phantoms covering the Migs, strike force entering the Red River Valley. Forty miles from target, moving ten miles a minute. The 57 and 100 mm flak begins to blossom in the formation. I’m concentrating on navigating to the precise roll-in point. Visibility about four miles.” I’ll see the target twenty seconds prior to roll-in. No time for corrective maneuvers, and even thought I’d like to glance at the target photo resting beside the windshield, I can’t spare three or four seconds. There it is ___ the bridge. “Omaha Lead rolling in.” In peripheral vision a SAM explodes just ahead and level. I stroke the burner to accelerate to 580, the ideal dive speed. Out of burner, stabilize on speed, sixty degrees and correct for a slight left drift. “Look out! A Mig just passed me coming straight up out of the target area ___ passed me canopy to canopy” Release bombs and pull up right, seven Gs, vapor over the cockpit, visibility at that moment zero. All sixteen on and off of the target in less than a minute: A tight, precise maneuver. The 37 and 57 mm so thick it looks like overcast. The bombs are all over the bridge. “Winchester Two is hit!” “I have you in sight, Two. Looks like smoke coming out. Two! Head for the Ridge!” “There’s a Mig coming up on Two. Give us some help.” Omaha Lead coming around left. Where’s the Mig?” He fired a missile --- missed Two --- and headed down. I’ve lost him in the haze.” Winchester from Omaha: steer 250 degrees for North Station. I’ll alert the Jolly Greens. Ozark and Gunsmoke: head out to the tankers.” “Winchester Two here. Flameout! I’m getting out!” “Three here. You’re on fire from the cockpit back.” Silence! Then the beeper. “Three here. He’s out. Got a good chute.” The beeper continues: a heartbeat. “Omaha to Winchester. Let’s head for home Rescue impossible this location” Only the beeper, as we turn toward the post strike refueling area. We maneuver to avoid more SAMs, and the Phantoms still cover us against the Mig threat. Post strike refueling is routine at 24,000 feet. We head for home base at 0800 ---- a beautiful morning with the sun still low, streaming between the cumulous saddlebacks. (Note: Winchester Two was taken prisoner by the Vietnamese in August 1967. He was released with the American prisoners.)” Colonel Mervin Taylor, U.S. Air Force, Rtd. That remembrance deals with one of the 118 missions Merv Taylor flew over North Vietnam in 1967, and it was typical. I had flown with Merv and his identical twin brother Irv in my first assignment out of flying school, the 1st Fighter Wing, 27th Squadron. The twins and I went our separate ways to combat in Korea.

One day the twins parted with a ‘See you later” in the barbershop-hooch of a base in South Korea as Irv went to the flight line for another combat air mission of ground attack in the F-80C jet. It was the last time they would ever see each other: Merv lost his other half that day. Merv arrived at Korat Royal Thai Air Base, Thailand ahead of me, assigned as Assistant Wing Operations Officer, a non-flying job. Insisting on flying combat, he wrangled abbreviated F-105 training in Japan. In spite of the extreme trauma of losing Irv in combat and finishing his Korean tour, Merv volunteered to fly combat again, this time again in ground attack on the highest risk missions in Vietnam. To him it was a call to duty and an obligation. Merv Taylor epitomized the pilots who took on that daunting and hazardous task: men whom I am so proud to have the honor of calling my comrades. As good fortune would prevail, I flew missions in the same squadron with Merv. A 34th squadron party was held when we arrived, to award some of those nearing mission completion and welcome the three of us.

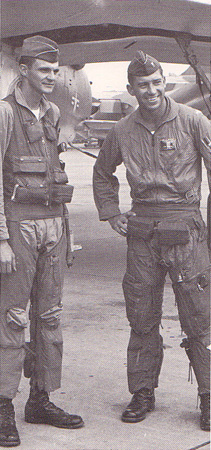

We hurried to the city of Korat, my first of only two visits there, to acquire black “formal flight suits” for that event, which were adorned with the usual flair of military patches, one especially pleasing was to tell the leaders of North Vietnam to shove it by choosing their favorite expression for American Pilots, “Yankee Air Pirates!” .

Actually, I found limited use for it after our dinner with new squadron mates, as the tempo of maximum effort strike missions had reached a peak. Being my first contact with Merv in 16 years, it was a very happy reunion and it was combined with a celebration of his new rank of “Bird Colonel”. The party was especially timely for us to meet many of the 34th pilots we were beginning to fly missions with and to accept our first symbolic mark of acceptance to the 34th. A few squadron pilots were awarded the 34th “Blue Max” after 90 missions, the point at which each was declared “Golden”, signifying they could decline the most hazardous missions, if they chose, including George Clausen, whom I replaced as squadron commander.

We new guys were awarded the “Snoopy”,

imaginary friend of the real life dog, our

Wing mascot Roscoe.

After arriving at Korat, I spent every day of every week for the next seven months on duty there, with the exception of two breaks of 3 days each in Taiwan. The only exception, some months hence, was a C-47 Gooney Bird round trip for an evening and dinner in Bangkok to talk with an editor of Aviation Week magazine for an article on our combat missions. On that flight, I escorted the casket of our squadron mate, Billy Givens, for his final journey home. He had been killed on a ‘go-around’ for landing at Korat, after returning from a mission, so like others was not counted in the combat losses. The memories of my combat tours in Korea and Vietnam both have the bitter, sweet content of losses of friends and comrades mixed with some of the most exciting and challenging adventures and camaraderie of my life. Our Wing Commander, Col. Edward Burdett was new to his job, as was his Deputy, Col. John Flynn. They were both outstanding leaders and brave gentlemen, with very different personalities. Ed Burdett was very serious and dry, making him difficult to relate with. John, with whom I trained in Wichita, was very jovial and open. John’s introduction of me to my new Wing Commander pointed out, with some admiration, I suppose, that I didn’t fly with a G-suit, and I had not for many years. Burdett said to me, “Don’t you ever climb into one of my airplanes without a G-suit!” and I never did. The crew chief was always kind enough to carry it back down the ladder to await my return from the mission. John was one of the finest individuals I have ever known and because he admired my flying in training, he assured that I was reassigned from our sister wing, the 355th at Takhli to the 388th at Korat. I was given command of the 34th Fighter Squadron, one of the two attack squadrons. The other was the 469th, while the 44th, a smaller unit than strike, was assigned strictly for surface to air missile (SAM) defense. Traditionally combat fighter pilots came directly from TAC fighter assignments, but that source dried up with the new A.F. goal for no pilot to have a second tour before others had their first. We had four lieutenant colonels assigned to and flying in the squadron, two of them senior to me, but I was selected as squadron commander, because of experience. That never was a problem, for me and I don’t believe it was for them either, in fact they could get on with combat flying and without the added responsibility for a 350 man organization. I never worked so hard or slept so little in my life as I did for those seven months. There was a great difference between experienced fighter pilots and the increasing number of others that were novices or lacking in pertinent flying, some limited to copilot experience in B-52s, a long reach to unique fighter skills. It required more courage to face the rigors of combat without the security of confidence in yourself and your aircraft. That increasingly greater problem of inadequate experience became a source of many difficulties and dangers in conducting our missions. The problems were exacerbated by the fact that the tempo of combat operations was too great to permit any training, flight or ground school. Maintenance test hops were the only non-combat flights, solo and for the experienced. One of the fine leaders in the 34th was Major Roger Ingvalson, who became an excellent Operations Officer was valiant, but was shot down and became a prisoner of war. Roger was an excellent and experienced fighter pilot with 4000 hours in fighters, 1600 of them in the F-105. He recalled an example of a typical mission and the difficulties for the unskilled and inadequately trained and it’s outcome: “I guess that my most emotional experience as Operations Officer was dealing with a pilot from my cadet class in 1952. He was enthusiastic but a very weak pilot. He stayed in trainers, and performed well as a “Mosquito” pilot, flying hazardous forward air control missions in the Korean War. But he yearned to be a fighter pilot, all those years, though never got a chance. As the need for replacements grew he was able to fulfill his wish by volunteering for the F-105 school and a tour in Vietnam. After six brief months of limited flying, like too many others, he was sent to join us, under some of the most trying conditions of weather and combat tactics. It had been nearly 16 years since I saw him and he couldn’t wait to relate his life-long dream coming through. On his third mission, typically in an area of light defenses at that stage of his tour, he was returning to good weather at home plate. They encountered some weather enroute to Korat and he made a cardinal sin when he fell out of formation and failed to turn immediately away from formation. In attempting to rejoin, they had a mid-air collision and he bailed out above a thunderstorm. He died in friendly territory. The leader landed safely with four feet missing from his right wing.” We had more than enough fine officers killed as a result of direct combat to make seemingly unnecessary sacrifices very difficult to endure, and the risks were imposed on the whole team, not just the unskilled. Because of the demands that two major combat missions daily placed on us, especially those pilots who had significant management, there was little time for anything but work. For all, nightlife was curtailed, as we were up shortly after midnight for morning missions and finished debrief after dark for the afternoon strikes. The old movie vision of heavy drinking fighter pilots was not to be found. Ground crews worked around the clock and I assure you that you have never suffered mosquitoes like those on the flight line all night, in Thailand. And the greatest attractor for them is jet fuel, JP-4! Just visiting them on occasion made me wonder how they put up with that! They not only did it, but I have never found aircraft more excellently cared for and serviced. Weather permitting, we flew two maximum effort strike missions to the heartland of the enemy each day, plus individual flight and element combat sorties to lower threat parts of North Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Even the latter could not be taken for milk runs, accounting for the loss of large numbers of F-105s and crews. Only missions to NVN were “counters”, 100 missions counters being the ticket home. A week on Rest and Recuperation, except for a few in leadership, affected pilot availability. The relished brief flight-line celebrations of tour completion, 100 Mission Parties, led to the frequent arrival of replacements. And the lack of fighter experience with many of the new arrivals provided a challenge in scheduling combat sorties and especially in developing the necessary teamwork at a flight level. Thus, the face of the squadron was in constant change, and without the opportunity for training. I hadn’t been there more than a couple of months when we added a squadron sign in front of our hooch area and many new faces appeared in a photo. Only the names of “old heads” from a few months before are underlined, to give a sense of the impact of change. And with each group of new guys the percentage of fighter experience declined.

I cannot properly recognize each of the young heroes in the earlier photo who helped me get up to speed in a few weeks. For all, there was only “on-the-job training” because of a heavy combat schedule. Sometimes I learned on their wing and sometimes with them flying mine. One of those was Clyde Falls, who was very aggressive, which I liked in fighter pilots, if they had skills to go with it, as he did. His wingmen on his 100th mission told how he “hung it out” going very low in his attack on trucks with this 20mm gun. As he parked after the mission to his celebration, crewmen were surprised at a hole in his bird where a 37mm shell had come up through the belly and didn’t explode and then went right up through the cockpit and out the canopy! Sadly, Clyde was killed in an F-106, about a month after returning to the States. One of the newcomers, Bill Thomas carried courage to the top, after we left, flying 200 missions. He survived to surpass Capt. Karl Richter’s 198, but luck was unkind to both and Bill, a gentle man, as well a super jock, was killed in an operational accident in an F-105, like Karl also was, before he secured that amazing number. Karl Richter and Bill Thomas epitomize the courageous young fighter pilots. Karl earned special recognition by downing an enemy MiG early in his tour, at the ripe old age of 23.

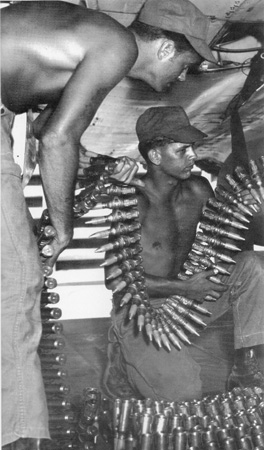

In the first two months of my tour, 35 F-105 crewmen were downed. That introduction to combat put the odds of getting shot down in 100 missions as a near certainty. And my squadron’s loss of three of our 16 pilots on one of my earliest missions in a way made the tour easier by virtue of accepting that risk early on. Time proved the cause of that extreme loss rate, was that almost every sortie was on strike missions to the highest threat areas twice daily. As weather patterns and political targeting decisions from Washington targets varied so did that equation of death, and we endured our highest risks right at the beginning. Significant risk was always there. Every person at Korat played a vital role in our mission, but none worked harder and under more trying conditions than our flight line crewmen. The around-the-clock activity was 365 days a year, and summer days could be unbearably hot, but it was nights that were torture. Mosquitoes abound in Thailand and they love three things greatly: Nighttime; Aroma of Jet Fuel; and Human Blood. Those crew chiefs, weapons and systems specialists, refueling crews etc, on the line at night paid in very hard work, under terrible conditions. And daytime was no picnic.

The squadron strength was well above normal manning because of the endless efforts, averaging about 350 members. Changing personnel was the norm, but we gathered, with the available squadron pilots on the wing, and available day shift of line personnel for a photo tribute to all those who worked so hard with so little recognition. I stood in the cockpit, alongside the available pilots standing on the wing, thin and tall with optical distortion from the wide-angle lens. A representative group of our day crew from the flightline joined us in front. I have had both pilots and crewmen contact me, even recently, as they learned of the photo through the grapevine.

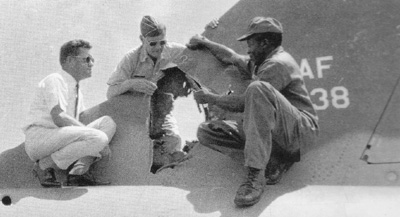

The F-105, Thunderchief was an airplane that had endured much maligning in its early years, including my own jibes, when my buddy Howard Leaf was nearly killed while testing one at Eglin AFB. So many examples of that old bird’s durability tell a tale of saving pilots, and both sometimes returning to fight again.

The two strike Squadrons each had about 30 F-105D and the Wild Weasel squadron about 15 two seat F-105F. I might add that the picture of Maj. Bill McClelland standing up in the hole in his wing was almost duplicated by another heavy AAA round in the wing of an F-105, which Col. John Flynn also brought safely home on one of his first few missions, and like the others they went right back to war; pilots the next day and airplanes with a new wing and patches elsewhere.

The F-105D was the only fighter in our arsenal that was capable of the required long-range conventional bombing sorties, with its payloads and durability. Though not the original intent, the capability existed in spite of its being designed as a Mach 2 nuclear fighter-bomber, with an internal bomb bay. It was capable of supersonic speed on the deck. That kind of speed was out with external stores, but high speed was treasured on bombing dives and exiting the target areas. The Thud offered versatility of multiple weapons stations on the wings allowing: two 3000-pound bombs, midwing, or the capability to carry six 750-pound bombs on a belly-mounted Multiple Ejection Rack, added to combinations of external jamming pods, air-to-air missiles, or air-to-ground missiles on additional wing stations. The D could also carry two anti-SAM Shrike missiles, fired on Weasel command when escorting anti-SAM Wild Weasel airplanes. And we carried two 450 gallon wing-mounted fuel tanks with the 750s or a 650 gal. belly-mounted tank with the 3000s. The nuclear bomb bay was converted for more internal fuel.

Its integral, 6000 rounds per minute, 20 mm Gatling cannon had limited use for our primary missions, but was valued to protect downed pilots and the chopper crews extracting them from the jungles, and also downed a few Mig fighters along the way. It protected downed flyers a few times and

also served to destroy MiG

fighter aircraft and I found it a great

hunting gun, for enemy fuel and supply

trucks, on the way home from our primary

missions to Hanoi. A two-seat version, F-105F, upgraded to G-model in the last part of the war, were two seat aircraft with a specialist in the back, equipped to detect and locate surface to air missile (SAM) sites and deter their effectiveness or destroy them with radar seeking missiles and standard munitions. Two F’s flew with two F-105Ds to form Wild Weasel flights, which escorted our strike missions. That bird, at 50,000 pounds, was as heavy on take-off as a fully loaded B-17 of WW II, carried as much weapons tonnage, but with one crewman and one engine. “Thud” gained endearment from its pilots in Vietnam, a war that ended its life, as well as the lives of many of its crewmen. That bird had one Achilles heel, where the dual hydraulic control systems merged below the rudder. Barring a major hit there or in the engine, it could often fly home seriously wounded, sometimes to fly again.

The fact that many downed pilots returned to fly again says a great deal about their courage and even more about the guts and skills of our Air Rescue crews, who faced great risks to extract downed flyers, whenever the environment was not so bad that recovery was impossible or the distance out of range. They willingly risked death or capture if there was the a chance of saving crews. But the distance was too far, and the odds were too impossible in the heartland of North Vietnam (NVN). |

| previous section | next section |