Chapter 4 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

|

Chapter 4 - Approach to Space click on the links below for more of the story... i. Test Pilots & Operations - ii. Experimental Testing - iii. F5-A Freedom Fighter - iv. Variable Dynamics - NF-101A - v. Anchors Aweigh - vi. Two Strakes - One Strike! - vii. Whirlybirds, Spinning Wings? - viii. The Rest of the Story |

|||||||||||||

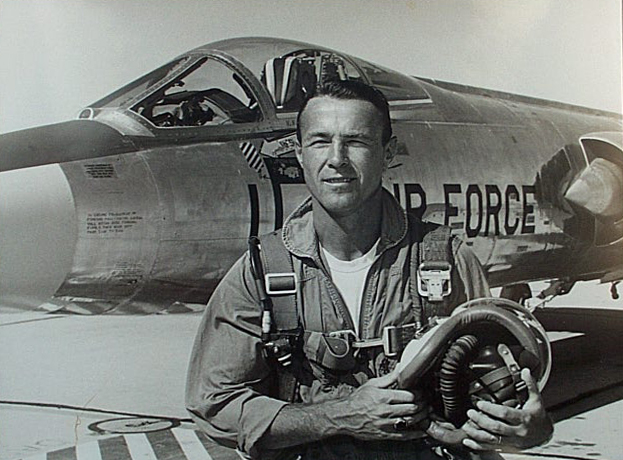

Test Pilots & OperationsAerospace

Research Pilots School, Edwards AFB,

CA, 1962 Around the mid 50’s the dual role of the USAF, the traditional manned aircraft limited within the atmosphere and strategic missiles in space, were unquestioned. There was a third arising in some quarters, and being supported by some within the Air Research and Development Command, maybe not whole-heartedly by the Commander, General Bernard Schriever, because he was the key man in the missile programs. There was a perceived need for seamless transition between the environment of air and space that could tie traditional aircraft and ground take-off with manned spacecraft and return to landing, for military missions.

That effort began in earnest and a manned spaceplane, the X-20 Dynasoar began design and development under contract with Boeing Aircraft in Seattle WA. Concurrently, AFSC authorized the A.F. Test Pilot School, located at Edwards A.F.B. to add an advanced course for experienced graduate test pilots to study science and technology and make them ready as space test pilots for whatever would result. The school was designated Aerospace Research Pilots School, and was under Col. Robert “Buck” Buchanan, a graduate of the TPS, Class 51A.

The first assigned pilots, Class I, were selected to develop the curriculum, including flying and simulation training as they studied and self-trained for the role. They proved to be an exceptionally competent group as demonstrated in the curriculum and in an exceptionally brilliant idea for a special space trainer.

I joined my mates in Class II of ARPS: A 6-month graduate course for selected military test pilots to gain special flight and ground training for space flight.

We had begun our studies when the announcement was out that NASA was beginning the process of selecting its second group of astronauts, designated Gemini Astronauts for the second space vehicle, a two-man capsule to be launched into orbit by the Titan missile instead of Atlas. That took one of our primary instructors, Frank Borman and me away from the ARPS for a period of time, when we were designated by the Air Force as candidates. It was an interlude that completely distracted us with so much riding on the outcome, at a time when most of us could think of nothing more exciting than space adventure.

While the Navy and Marines submitted all test pilots who met the NASA requirements, the Air Force went through its own evaluation of qualified test pilots and determined which would be submitted to meet the exact number, eleven, that NASA would select. It was clearly an Air Force decision to pick and choose those who could be assigned, which may have seemed arrogant in the eyes of NASA, since Navy sent a larger group of all filling the requirements, as did Marines. NASA also had candidates, including Neil Armstrong. Likely, politics demanded some of each, except for the marines who had only two applicants.

Our final preparation was what we dubbed ‘Charm School’ in which a PhD in Semantics or some such thing and three others trained us for the NASA interviewing and the final board assessment. We had to dress in civvies for the occasion of our “finals”, a simulated interview, and were critiqued on our demeanor, responses and even our attire.

We were sent into an ultimate evaluation, up to and including a group interview with Gen. Curtis LeMay, Chief of Staff, in his office. One thing I took from that meeting was the fear that Chief held over senior officers and there were many tales. One of our gang asked the 3-star general, DCS/Personnel who was leading us to the Chief’s Office, whether we should salute individually or line up and do it as a group. His cop-out was to do whatever felt best under the circumstances.

We were finally ready and submitted to NASA, upon which only Joe Engle and Neil Garland were rejected by NASA for their evaluation and selection process. Among required personal actions to NASA, was a written request for acceptance and recommendation letters and once again, Jimmie Doolittle took time to be one of my sponsors.

An interesting side note is that, less than a year later, Joe Engle passed more experienced test pilots to fly the X-15, then voluntarily left that and became Mission Commander on the second Space Shuttle flight, with pilot Dick Truly, who had followed us into ARPS and became a NASA astronaut and later the Administrator after his own space adventures. Dick, a Naval Aviator, was in TPS shortly when we graduated from ARPS. NASA’s final selection process, after our physicals, took place at Ellington A.F.B., near Houston, which was a de-activated Air Force Base at the time, but we were housed in the barracks there. A strange sidelight for a deactivated and closed base, was that the barracks and a mess hall were opened for us plus the Houston Oilers professional football team, of the fledgling American Football League, who were in residence at the base for their spring training. The old adage that politics makes strange partners sure held there, but I suspect the base was under state control at that time.

We, candidates for astronaut qualification tests, and they, for professional football selection, were showing our stuff. We would watch them practice in the evenings and I’ve never forgotten the smallest lineman ever in the pros, was a diminutive offensive guard even by standards of that day. I can’t recall his Italian sir-name, but I assure you he was a professional hit man. He weighed less than 190 pounds, as I recall, but quick as a cat and he would pick a fight with a defensive lineman at least once every practice, and they all outweighed him by many pounds. He was a starter for a number of years and an all-star selection in the AFL and he sure proved another old adage about the size of the fight in the dog.

We finally faced the NASA selection board, including Deke Slayton, who had been removed from astronaut flight status because of intermittent atrial fibrillation of his heart. Deke became one of the most powerful men in NASA and in later years negotiated with the NASA Administrator to trade a flight for himself on Skylab for ceding his position in NASA, as Chief of the Astronaut office, forever relinquishing the power of the Astronauts’ Office he had wielded in all facets of the programs. Some of the astronaut crewmembers considered it a virtual sell-out for personal gratification. He had waited so many years and their unique power in all the design and political issues was missed in the Shuttle program.

One might wonder whether the oversight on specifications and testing of the Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster, which caused the Discovery disaster, might have been avoided with the unfettered and guarded oversight, which had been the domain of the astronaut office. The primary cause was clearly the failure of the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center and it’s contractor Thiokol to willingly impose the Shuttle Specifications of the lead, Johnson Center in Houston upon themselves, and resulting oversight that engendered a failure to meet specified outside air temperature requirements in their design of SRB segment joints. I know that first hand, because as the Vice President and General Manager of the Shuttle External Tank, I was initially considered primarily at fault, until data, photos and a segment of the tank recovered from the ocean proved otherwise. We had to insist on the Shuttle Specification #7700 to assure we never missed a requirement in our design when we won the Tank contract in 1973, but thankfully we held firm on that.

It is sad that the thermal protection once again has reared its head in the recent Columbia disaster. Although it appears that NASA is finally getting serious about addressing this repeat disaster, no solution will be high fidelity with the current Shuttle.

To their credit, all five of our Gemini guys flew on Gemini and made lunar flights, except Ed White, and he will be remembered as the first person to perform an untethered “space walk” using only a crude hand-held thruster gun on Gemini. Ed, son of an Air Force general was a gentle and fine man, who perished in the Apollo fire on the launch pad, along with another Air Force friend and fellow fighter test pilot of our time, Gus Grissom and their comrade, Roger Chaffee.

The first Gemini mission had not yet launched, and it was a great disappointment for me to miss the big events of the future, when I found after returning home that I failed. I remember, before we left Ellington, after the final events finished, NASA gave us a party with the 7 original astronauts. Gus Grissom told me how little they got to fly, except in travel in a T-38 jet trainer, how much time they spent in engineering reviews of the spacecraft and that he had been home only five days in a year. That didn’t deter him but it certainly was not a lifestyle for everyone, and not for many families, which is one of my consolations. There were other consoling occurrences for me over the years, mostly the great flying and combat, but I would have traded those for one great big event. At that moment it was too exciting to avoid.

Meanwhile school went on, since I was the only student affected and I was in the selection process with two of the students from Class I, Borman and McDivitt.

Frank Borman was not only our instructor but also my Instructor Pilot for a re-check in the F-104; it had been three years since my prior check flight in it. Frank was an excellent and experienced teacher, having been a West Point graduate and an instructor at the Point earlier in his military career. Being with Frank and studying with Mike Collins for the NASA process, during our brief periods in Washington and the final selection at Ellington Air Force Base, helped me to keep up with the missed academics back at school.

This brief respite from the ARPS was actually a very enjoyable period and especially getting to know Mike, a wonderful, unassuming guy, with whom I would soon be working at adjacent desks, and later pulling for on the first lunar landing mission, Apollo 11.

Many years later, Martha and I had the great pleasure of a dinner in New Orleans and ride on a party boat down the Mississippi with Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and finance’, and Mike and Pat Collins in celebration of their 15th Anniversary of the Lunar Landing. I was Vice President of the Shuttle External Tank program for Martin Marietta, where we spent 13 years in that city. It pays to hang out in fun places.

That was also my last meeting with Mike, but not with Neil. I was fully responsible for the Shuttle external tank from engineering to construction and when Challenger went down, it was initially presumed to be a tank failure in one of its miles of welds. We took x-rays during construction and, since there are seldom to be perfect welds, two independent quality control readers evaluated every inch of both the liquid oxygen and hydrogen tank, the latter being the point of failure, initially identified from the accident videos. If a flaw exceeded certain limits repairs were mandatory, otherwise the structure was sound. A check of all the x-ray exams, immediately after the accident, located a flaw near the point of the explosion, which had met inspection criteria and was recorded. I don’t have to say what a stressful position it was to be the senior person absolutely accountable for the quality of that external tank, and the systems engineering manager during early design. After a while, sophisticated treatment of launch film close ups showed hot gas leaking from the SRB’s impinged on the tank at the point of failure, and recovery from the ocean floor of that exact piece of ET structure, still intact at that particular weld sealed the issue.

During this process, I worked with a national board of scientists and experts, among them Neil Armstrong and Maj. Gen. Bob Kutyna, Chairman, in establishing corrective actions within in entire process to reduce probability of another such catastrophic event. However, the probabilities exist for such a failure every few hundred flights, in high stress areas like the SSME pump turbines, the tiles and flight controls.

I can’t resist a final comment on one of two great American adventurers and explorers. Neil reminds me of Lindberg in every way, especially eschewing the fame he so clearly earned and retaining his privacy, self-esteem and character. A few years ago, I read about a teenaged girl who was fighting and seemed to be losing her battle with cancer, in Orlando, but she had a great attitude and mentioned her interest in the astronauts. I wrote Neil and she called me to let me know that he quickly contacted her. The story had a wonderful ending because of a full recovery. Sometimes such occurrences, rare as they are, reflect mind over matter.

There was a lot of insider gossip that some of the Mercury Astronauts were promiscuous, and NASA suppressed that with enforcement policies on the press. We joked about that when we were at Ellington for evaluations. Mike Collins reminded me of that in our last meeting and mentioned that he quoted me in his book, “Carrying the Fire”. I hurried to read it wherein he said that when we were getting ready for our interview with the NASA Board, he asked me what he should say if asked why he wanted to be an astronaut. He quoted me as, “Tell them you want a lot of strange ass.” Had he taken my advice, maybe I would have been on the first Lunar flight, instead of him! It was time to get my mind back to school. Our ground training consisted of astronautics, space mechanics, reentry, navigation, space physics, etc. We even went to a special course on human physiology in space at the school for training Flight Surgeons in San Antonio. My attendance at that school and chance encounters with its Director, Dr. Larry Lamb, proved fortuitous in my life and that of a neighbor and fine friend.

Our flying included Drinkwater Approaches, conceived by and named for a NASA pilot and engineer, which evolved into the gliding Space Shuttle’s landing technique, working perfectly for direct descent and landing without power. Of course Shuttle controls, guidance and instruments are more sophisticated but our approaches showed just how efficient the Drinkwater was. We used a standard F-104A with its communications to get a single initial point at a high altitude location. It was amazing to learn that with this technique we could fly visually, and with no further aids but airspeed, altitude and vision and consistently touch down on the runway within 50 to 100 feet of intended landing, without moving the throttle out of idle and most amazingly, no turns whatsoever. Necessary traits for such landing craft are a low lift to drag ratio and a means to increase drag significantly on demand, criteria for which the F-104 was well suited, as is the Shuttle. Low lift to drag can be equated to a Cessna 152 chock full of lead and both doors jammed full open, allowing them to close when stretching the glide. High lift to drag epitomizes the soaring gliders, which have so much lift and so little drag that even air currents will keep them aloft.

In one training flight, I was flying an F-106A, a beautifully stable and capable delta-winged jet fighter-interceptor, on a mission when I had a flameout, which proved to be the result of a malfunction of automatic controls for the engine intakes. I was too far away and too low to make a landing anywhere so I had no choice but to continue trying to get an air-start, since belly landing in a jet in rough terrain is nearly certain death. Air-starts had become so standard between fighters by that time, it was actually simplistic, but it wouldn’t start after repeated attempts. I continued to try as I was approaching my bailout point, there was no alternative, when inexplicably it restarted and I climbed to a safe altitude and made a precautious simulated dead stick.

We also performed maximum zoom flights with the standard F-104A in full pressure suits, but we remained under aerodynamic control, and jet power throughout. Those flights were challenging, I reached 86,000 feet and it provided some confidence for a future test program I would fly, but little more than that.

Another exhilarating part of our training was riding the human centrifuge at the Navy Lab in Johnstown, near Philadelphia. We could experience the different g’ profiles that the astronauts had or would encounter sitting in the three different capsules of the NASA programs, experienced on reentry into the atmosphere. Crew stations were designed to put them in the best position to endure the g’s in the best axis for a human, i.e. +X axis acceleration, with their backs toward earth and their bodies pushed by g’s against the backs of their seats. The force was most noticeable pushing in on your chest, and was a whooping 15 g on Mercury missions, 10 g on Gemini and 5 g, for Apollo. There is a lot of braking to be done in the steep entry of capsules, which were all drag, and little or no lift. The smaller the capsule the less drag in upper space, so the briefer but more harsh the deceleration at lower levels. In addition to those real entry profiles at ‘g sub x’, we did “Runs” in other attitudes, which proved very uncomfortable in some. The most hazardous was the “minus g sub x”, or eyeballs-out”, at 5 g, the force and direction you’d get in a head on crash with seat belt and shoulder straps, except it was steady-state. There was no doubt during those runs that, if the shoulder straps broke you, would have to be scraped from the front panel to be buried.

Another was “g sub z”, the usual acceleration force when sitting in an airplane and making a tight pull-up. That confirmed that I had a high g tolerance and got to 7 ½ sustained without blacking out (no g-suits), which was just a hair over the operating limit for fighters of that time, with significantly greater g’s before structural failure. I was seeing only through a very small tunnel of light, surrounded by black, known as ‘tunnel vision’, which all fighter jocks encountered at some time, before the advent of g-suits. After that centrifuge, I never wore a g-suit again, since the operating limit was seldom reached for much duration under any conditions.

There is some margin available when piloting an airplane that you didn’t get in the centrifuge. In an airplane the pilot knows exactly when g’s are coming, since he induces them, and can pre-tense every muscle in his body from head to toe before the blood has left his brain. That creates restriction in blood vessels throughout, just as a g-suit does for the midsection and legs. However, the centrifuge accelerated so quickly and without warning that the blood was on its way down, before the muscles could respond. An interesting thing occurred at maximum g level in a seated position. My feet turned almost solid black from a phenomenon called Patekei, due to the stress on tiny blood vessels in the feet, which lasted a while.

In my 7th decade of life, I learned to bare-foot water ski, only to find my feet burning hot on the water and I again faced blackened feet, but only very briefly and never felt the heat or saw that result in skiing, thereafter. I leave it to the readers or doctors to analyze those imprecise similarities, and I only got one shot at the centrifuge, but understood the outcome was repetitive.

Our training also included “flight” in a number of unique simulators at school and aerospace companies working on space flight. I spent a total of 13½ hours in Lifting Body, Semi-Ballistic Missile, Moving Base Orbital Rendezvous, Boost, X-20 Dyna Soar, Vertical Take-off And Land, and Space Docking simulators.

The school later acquired a more sophisticated, I presume, simulator but I never saw it, and they ARPS ended up losing opportunity to actually fly the missions it was designed to train, on a spaceplane, the AeroSpace Trainer. The day of the simulator didn’t really arrive until the advent of cheap and powerful digital computers were available. Even so, the training proved extremely valuable in my immediate future after graduation.

One simulation for control of orbital flight, displayed nothing but the three Oyler angles as a means of recognizing and controlling the spacecraft motion. Oyler angles are a rotational or angular reference zero to 360 degrees full circle, about the three orthogonal axes in Cartesian coordinates. They could be used to control attitude with good understanding and very deliberate and slow rates of rotation, no at all practical in a real task in space, like docking or any maneuvering. It did clarify angular responses in the students mind, and how the thrust levels and durations of space control systems affected the problem of vehicle control. It encouraged deliberate and careful decisions and control impulses, but that is not always practical, as I would discover in a mission requiring space control..

A docking simulator taught the complexity of the problems of docking two orbiting vehicles in space. It was extremely difficult with the techniques of the time. If two spacecraft are in the same circular orbit, one behind the other, they will remain so. Thrusting of either immediately changes its orbit about earth. A thrust in the plane of the orbit, along the tangential velocity will change the circle to an ellipse and the only thing retained will be the altitude at the moment of thrust impulse. This base altitude becomes the apogee of the new orbit if the thrust accelerated the vehicle or if the thrust is retrograde the starting altitude becomes the perigee. Any thrusting changes the period of orbit and the two will never again meet. A thrust in plane but not tangential will change both apogee and perigee different than the circular altitude in a new ellipse, making separation more rapid. Any thrust vector out of the plane of orbit also sends the vehicle on an entirely new path over the earth; and orbital plane change.

Any combinations are possible and the change will be the sum of its parts. Thus the astronaut sitting behind another vehicle in exact orbits who made any single thrust in an effort to catch and dock with the other vehicle would immediately start diverging from it, likely never to get as close again and losing sight over time. A near-perfect sequence of vernier thrusts, off-setting problems was possible, but very time consuming and difficult. What could be done?

The first way was to practice, practice, practice and still it would be very difficult without a starting point nearly nulled. The second was to find a brilliant mind to solve the dilemma. Dr. Buzz Aldrin, PhD, a qualified military test pilot, and second man to step on the moon, who is also a scientist, conceived a solution for control and guidance that made possible the lunar rejoins of Apollo and turned mating with Skylab, Vostock and Space Station into seemingly routine workday chores in space.

Bless him, at our advanced age, Buzz also was courageous enough to recently punch out a “smart-assed” young radical who accosted him and publicly accused him of lying and deceit in an alleged “government plot, which faked the Apollo Lunar Landings”.

Finally, our training in the X-20 DynaSoar simulator at Boeing in Seattle, was very realistic. That craft was to be the Air Force space plane, and our classmate Al Crews was to be one of its pilots. We learned a new flying technique using yaw rate alone to control roll and avoid disastrous instability from roll inputs and coupling. It was called ‘beta dot’, engineering shorthand for rate of change of yaw angle, which could be used for emergency re-entry in event of failed stability augmentation. The craft became uncontrollable with normal piloting at the high angle of attack required to retard entry in event of automatic stability control failure. By avoiding use of destabilizing aileron corrections, attitude control was possible with sharp pulses of the rudder, like a dihedral effect in flight. That technique later helped me hold higher angle of attack flying through re-entry on the AeroSpace Trainer, test program I would fly. Secretary of Defense, McNamara went to the plant for a brief review, shortly after our visit, and shortly thereafter he cancelled the X-20 program.

Later in our training, Col. Chuck Yeager became the school commander, although he was not around his office very much and I don’t even recall when or how we became aware of his transfer. One thing is sure, that his being there and his friendship with one of the nicest people I’ve known, B/Gen. “Twig” Branch who was AFFTC Commander, made our graduation trip top notch. The participants on that extended boondoggle were those two, our Hospital Commander, Dr. Stan Bear, Buck Buchanan, Art Torosian, the eight graduates and our C-54 pilot, Maj. Harry Andonian, a U-2 test pilot, who by this time has more flying time than any two of us, since he flew anywhere in anything with wings, at any time, and still does. One of us always flew as Harry’s copilot, a consideration for the taxpayers, I surmise.

Our ports of call were numerous, including Stockholm, as guests of the Swedish Test organization, with a fabulous special flight demo of their double dart-shaped ‘Viggen’ fighter jet. And Germany, without official duties, which might have been accounted for by the fact that Chuck was well known, especially in Germany, as a woodsman, so he and Gen. Branch spent their time in the forests. As an aside, those two crashed as passengers in a new Army helicopter out of Edwards, when the Army test pilot agreed to drop them off at a mountain lake, and crashed instead. Chuck had minor injury, and they avoided drowning, but the Army lost a helicopter.

A couple of days in Madrid followed, with a visit to the Spanish test organization, whose lab facilities at that time would not have stood up to our high school labs. They showed us their experimental jet engine in production, which appeared to have so much weight there might not be enough thrust to propel itself, much less an aircraft. Among the few airplanes on the flight line we noted a German Me-109 and a Nazi tri-motor transport, both still being flown.

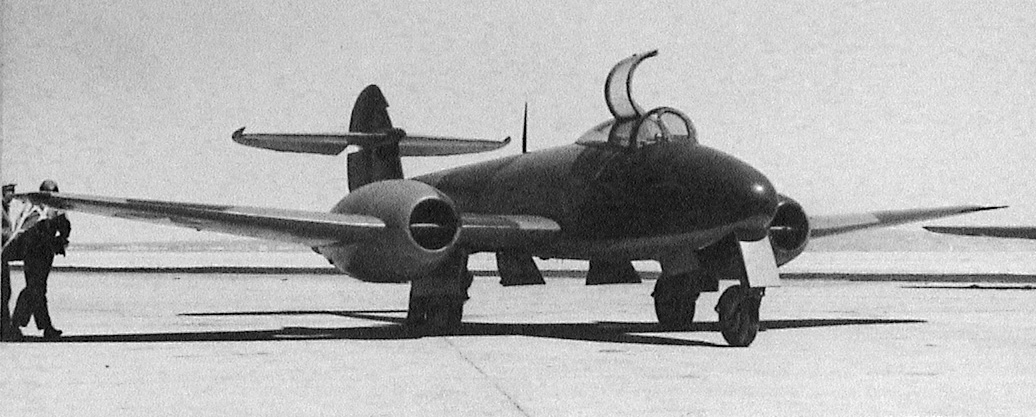

Best of all, was our time with the British Royal Test Establishment at Farnborough. The highlight of the whole trip for me was flying; to be turned loose in the Chipmunk, their neat little WW II trainer, followed by the old and first British jet, the Meteor. It was a single place, twin-engine aircraft almost ancient in the cockpit. The only instruction on any of my flights in four different airplanes that day was a briefing at the cockpit by a host pilot, who then climbed down and waved a tally ho! In the case of that old Meteor, there was an added advisory to “hold down the g’s a bit, mate, since she is getting on and has a bit of a crack in the wing spar”, but he assured a bit of acrobatics should be O.K. and it was, as least with a few rolls and easy loops.

I recalled the Polish Ace who gained fame with his invention, in a Meteor, of what has been called ‘the first new aerobatic maneuver since the Immelman of WW I’. I longed to try it, but thought better under the circumstances and the “wee crack”. That guy would climb vertical to stall, but as he fell back into a hammerhead he would cut one throttle and full power the other, and kick full rudder with the yaw direction. The outboard location of the engine provided enough torque to turn the airplane into a falling pin-wheel so that he could do 1 ½ full yaw rotations in the vertical descent before reversing the thrust and rudder in time to end up in a vertical nose dive. I can only presume that he had to do it at fairly low altitude to have enough thrust to get that result. I’d say that chap had an imagination even wilder than Yeager or Chandler, whichever one dreamed up their flip-over in the F-86. Their was one difference in that the Meteor had no ejection seat but a mistake in the “flip-over” almost assured you wouldn’t get a chance to eject anyway.

I can’t help but recall the Aussies at Kimpo, Korea, who arrived with their Meteors, briefed along with us, going for the Mig-15s and announced they would have an advantage over the Migs by flying above them. Aussies have guts and bravado, but it wasn’t too long before they had to withdraw to ground attack roles, after losing too many blokes to the Migs. One flight in a simulated dogfight with our old F-86A might have convinced them beforehand they were in the wrong role but they had no comparison until it was too late. In reading history of air wars this was so frequently an occurrence, Germans versus the Spanish and later against the Poles and Russians. I hope we keep history in mind as the Chinese Air Forces evolve with their evolution into a ‘dictatorial capitalism’, a la Hitler’s Germany.

I flew their Canberra, twin-engine bomber, from which our B-57 had evolved. I had flown the 57E, but the Canberra was crude, in comparison. It was lighter than ours but underpowered in comparison, because of engine evolution.

Finally, it was into the Hawker Hunter, which came along quite a while later than our F-86, but was quite similar in performance, being swept wing and with limited control boost. It was a good acrobatics aircraft, but was at least a generation late as a combat airplane. It would have done nicely in Korea, but came years too late to save the unfortunate Australian pilots who faced Migs with Meteors.

The trip to England ended with the Royal Air Force’s infamous ‘Dining In’, which starts as a formal military dinner with violins, violas and violets. The formalities ended with an extended and dull speech by the senior British officer, when the speaker very suddenly disappeared under the formally set dinner table, the victim of two young ‘Leftenants’, who crawled under the table and with each yanking one leg of the old boy, ended the speech and the dinner. Such action to a senior officer would otherwise be punishable, but Dining-In was a different matter, we presumed. From that point on to generalized inebriation all hell broke loose in competitive one on one physical challenge events, until the last man crawled away. Of course, the competitions were Brits versus Yanks. I saw one Brit officer split his head open falling into an iron radiator in a hallway, after being spun round head-down on a pole then a timed run up and back the narrow hallway: A brutal task for a sober man. The surgeon, a participant in the fun and games took a look at him dazed and bleeding heavily, pronounced, “This man needs medical attention!” then hastened back to the bar. A couple of blokes finally sacrificed to take him to the hospital, but hurried back.

I had heard many stories about the British pilots and their unusual humor over the years and it was reinforced, from the lips of one British pilot I trained with. He told me that when he was attached to an American squadron on exchange he had to bail out of an F-86, at low enough altitude to have his ejection seat impact not too far away. An hysterical woman rushed toward him crying and pointing because, “The other pilot’s parachute didn’t open!” He consoled here with, “Don’t worry Mum, he’s trained to point his toes.”

ARPS Cl III followed us with Al Atwell, Charlie Bassett, Tommie Benefield, Mike Collins, Joe Engle, Neil Garland, Ed Givens, Greg Neubeck, Jim Roman, Al Uhalt and Ernst Volgenau. Class IV was the final one, as a result of the Air Force’s loss of the space airplane mission with the cancellation of the X-20 Dynasoar. It’s students were Mike Adams, Tommy Bell, Bill Campbell, Ed Dwight, Frank Frazier, Ted Freeman, Jim Irwin, Frank Liethen, Lachlan Macleay, Jim McIntyre, Bob Parsons, Al Rupp, Dave Scott, Russell Scott, Walter Smith and Ken Weir.

Among all the ARPS students, only the following flew as NASA Astronauts: Jim McDivitt, Mike Collins, Joe Engle and Jim Irwin. Three others were selected as astronauts, only to perish in aircraft accidents before their chance to become astronauts: Charlie Bassett, Ed Givens, and Ted Freeman. Frank Liethen, a student for whom the school’s finest award was named, was also killed in a flight accident, as was Tommie Benefield, while testing the B-1A bomber.

Upon graduation, Al Crews, Don Sorlie, Ted Twinting and I were assigned to remain at Edwards and join the Fighter Test Section of Test Operations. Charlie Bock joined Bomber Test. For the first time since my return from the Korean War, our family began a reassignment without having to find a new home and new schools.

|

| next section |