Chapter 2 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

Chapter 2 - Aerial Combat click on the links below for more of the story...

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

ACES ARE BORN: THE EYES HAVE IT! 4th Fighter Wing, 335th Squadron, Kimpo AB, Korea: August 1951 - April 1952 I left my heart in San Francisco, Martha that is, for the 4th Fighter Wing. We sailed from the Port of Oakland and I had my only ocean cruise on the Aiken Victory, a typically slow victory ship of WW II vintage. The trip was boring, but food onboard was plentiful and good, so compared to the seasick Army troops in the hold, we had it fine. We arrived in port at Yokohama Japan.

The few of us assigned to the 4th Fighter Wing went by bus to Johnson Air Base, which required an extended drive through Tokyo and surrounding towns, by a Japanese driver. It scared the hell out of us to see young children, carrying babies, dart across streets one lane wide by our standards, but with opposing traffic, including our bus. Our Japanese driver seemed oblivious to their safety and unfamiliar with the brake pedal. The local trucks and oxen drawn carts of barrels filled with human excrement, known as “Honey Buckets”, competed for the space and added to my fear for the young ones, but we arrived without incident. The air war was growing but the 4th Wing, with two fighter squadrons were in Korea flying combat on an alternating schedule with the 336th at Johnson Air Base near Tokyo. Our squadron the 335th, returned to Tokyo while I completed training, 7 flights from 11 August through 3 September 1951. While in training, a prime topic of conversation was Lt. Jim Lowe, who, as a wingman had gotten his two MIG-15 kills by leaving his leader, or so it was said. He had been recalled to the States for a publicity tour before we arrived. For us it was a real dichotomy, because we each dreamed of a victory and we had great respect for our belief in almost sacred obligations of a wingman to his leader. We were proud of our role, yet envious, and maybe rumors distorted the real facts. I never saw or met him because he returned after my tour ended to become an Ace with 9 kills. He certainly had the skills and courage, which acquitted him as a flight leader, with the eyes for acquisition and victory, whether or not an outstanding wingman’s attitude. I have wondered what he expected of his wingmen. Football in the early 1950’s was a metaphor for air combat at that same period. The hero of the game was the flashy running back, who carried for the touchdowns and posed for the pictures. He had great courage and wonderful skills. His unsung assistant was the blocking back who, hardly noticed, protected the runner and made the runner’s most memorable accomplishments possible. In aerial combat these were the Ace and his wingmen. Another difference was that in air combat the greatest threat was from the rear. The hardest job for a wingman in those days, before radar and self guided air-to-air missiles, was to fulfill two primary responsibilities. Never lose your leader, or more accurately, never let him lose you, and he’d damn well try, unintentionally. The other was to warn the lead of any aircraft that were an immediate threat, which meant approaching firing position from rear quadrants. When patrolling an area in spread formation it was possible to cover each other, but as soon as enemy sightings occurred the formation closed more into trail, to prepare for maneuvering. That was when the wingmen really earned their keep, and lost the benefit of mutual protection. The problem with these two rules was that they were almost mutually exclusive. Never losing him required attention to the leader in front of you and covering his butt from attack required primary attention to the rear. Maintaining position to protect and react were key and required constant knowledge of where he was and how he was moving. Combat fights were generally conducted with minimal radio chatter, contrary to old war films, and leaders didn’t announce maneuvers to wingmen, they just suddenly, frequently and rapidly changed direction. When flying without much turning, staying with the leader was a walk in the park, but when flying straight seeing an attacker before his bullets hit was problematical. That was the most hazardous situation for the wingmen, especially number four, tail-end Charlie. Every would-be Ace’s favorite target was number four in a flight straight ahead! Nevertheless, it was the wingman’s priority to hang in there and notify the leader, if at all possible. On the same day that I completed my final training flight, I ferried an F-86A to Kadena Air Base Japan in the afternoon. I caught a Gooney Bird, C-47, ride to my new home at Kimpo Air Base, Korea the next day. New pilots were detached to a squadron in combat, if their squadron was at Johnson to avoid delay between training and initial combat. I reported to the 334th squadron, commanded by Maj. George A. Davis, Jr. and was assigned to Capt. Ralph D. “Hoot” Gibson’s flight.

After arriving on the 4th of September, I flew my first two combat missions on the 6th and 7th, however no MIGs showed up, ready to fight, only calls of sightings from our radar on Chodo Island, off the coast of North Korea. I got a good look at our primary combat zone, known as MIG Alley, which was a large, area in the northwest corner of North Vietnam. The alley was bordered on the west by the shoreline of the Yellow Sea and on the north by the Yalu river forming the Chinese border and stretching from Sinuiju city east to the Sui-ho reservoir. That was the infamous spot from which the Chinese had invaded to reclaim North Korea and drive us to the Pusan peninsula. MIG Alley’s southern line started at the city of Sinanju eastward along the river to Huchon, although on occasion, the MIGs would journey as far south as Pyongyang, their capitol. I was pleased when I met Ken Chandler, the pilot who had flown with Chuck Yeager in the movie Jet Pilot. I was especially impressed later, by his performance on a notable mission. He was leading a flight with his wingman, Lt. Dayton ‘Rags’ Ragland, our wings only black pilot, a real prince and a favorite of all of us. Ken left his element high, providing cover, and took Rags to attack the North Korean Uiju Airport near the Yalu River when they spotted 12 parked MIGs, an amazing sighting. Kenny destroyed 4 MIG-15s and damaged several others. That feat and his handsome countenance earned him an introduction to visit with Susan Hayworth, the very famous and beautiful Movie Star, when he finished his tour. We got the news from home and there was envy to go around. On the afternoon of 9 September I flew my 3rd mission, as wingman on Capt. Ralph “Hoot” Gibson, who along with another Captain Richard S. Becker from the 336th, were contesting to become the second jet ace to follow Capt James Jabara, the first ever. PHOTO 102 copy, “First Jet Ace in history, Capt. Jabara.” Both had four confirmed kills. I was surprised, enthused and most of all impressed, that a Flight Commander with so much at stake would allow me to fly his wing. It showed the kind of man Hoot Gibson is, proud, fair and courageous and cocky as hell! He would later lead the Thunderbirds, the Air Force acrobatic team, further testament to his skills. That day proved to be the most memorable of that entire tour of duty, my baptism under fire and among the most treasured memories of my flying career. I’ll never forget my first impression, when an unbelievable gaggle of airplanes approached us from across the Chinese border, as we patrolled in our 16 airplanes. I knew there had to be more than 50 and the official report was 70. I wasn’t counting, but there was a feeling of bravado to proceed toward them. I saw greater numbers on later missions, but that first view was nothing short of staggering. The fact that each MIG produced a swirling and expanding contrail made it all the more impressive. I heard that often they would just pass over, so the excitement was heightened as they started down on us. We jettisoned already empty drop-tanks and engaged them and I found myself a spectator, watching Hoot shoot down the enemy, but most of all a busy worker, trying diligently to clear to the rear, while we were tracking some evasive efforts. I was terribly intrigued by the sight of a real aerial attack and that first encounter seemed almost surrealistic. An intriguing part of it for me was the sight of a large number of vivid sparkling impacts from Hoot’s armor-piercing incendiary bullets as my head would pass from one side to the other to clear our rear. It was surprising to see so many hits and little apparent damage, having seen films of the explosion of airplanes in WW II, so suddenly. But jet fuel (kerosene) had replaced high-octane gasoline. Hoot was hitting the MIG with great precision, and smoke began, then fire and the enemy was a goner.

In no time Hoot was closing toward another MIG , but four MIGs were cutting us off and closing on my tail to firing range. I advised Hoot, who told me to keep watch and advise him if I had to break off. The lead MIG started shooting far enough out that the red fireballs were falling short, but then he closed and fired a burst, not very high over my right wing. I guessed he was using his two 23mm because the cannon shells were coming at a faster rate than a single 37mm gun. Too near for him to miss for much longer, I notified Hoot I had to break hard right and then told him that all four MIGs were sticking with me. He asked if I could handle it, and I had to say, “Yes”. Pride with a touch of bravado prompted me to say that I could, but I soon lost the bravado. I guessed that I could easily shake those birds, however we were near Bingo fuel, minimum to head home, when this occurred and I knew I had to get away from these guys quickly, therefore I couldn’t sacrifice precious fuel in a long encounter, or give it up by an extended dive. I decided to beat them quickly with speed and high g turns. I made a diving turn to gain a speed advantage, pulling just enough g’s to make it unlikely they could draw a lead and hit me, then I suddenly pulled hard while holding the trim fully aft, since I had an ‘A’ model and was in the speed range where that model’s elevator pulled like a rubber band with little g response without it’s stabilizer re-trimmed. Suddenly something occurred that I had never encountered, and I found my head down in my lap in extreme g’s for an extended period. I didn’t notice side-load associated with a snap roll, a possibility, and I have always surmised a run-away trim was my problem. I never used shoulder straps in Korea, the better to clear, and I literally could not look outside, my head was in my lap. All efforts to push forward and re-trim were useless. In spite of the concern for the MIGs, I extended speed breaks and idled the power, and when I was finally able to raise my head again was climbing steeply, but was below 5000 feet, still in the MIGs’ home area, very far from home. At that point I clearly had real fuel problems and started a long climb to the south, when the 4 MIGs, reappeared and began a series of high-side firing passes on me like I was the target in gunnery school. I guess they had circled down to get into position for attack. On the first attack, I found that my ailerons were restricted allowing very slow roll response, which became an extreme risk as the MIGs began making successive passes. I never have understood why they didn’t slide behind for an easy kill, but I was moving generally south and at the lower altitudes, so they probably were uncomfortable there and feared slowing down. I’ve got news for them, if those guys felt threatened! In spite of my restriction from a quick break, I knew I didn’t dare start any break early and entice them into a deadly tail chase so I waited until they started firing and got close on every pass, the better of the two evils. I would struggle mightily but get only a gentle turn into them, but force them to deal with a bit higher angle off. That made their gunnery a bit more difficult. An effective break would have required sudden maximum roll, followed by an equally sudden application of high g’s. The very slow roll into my break seemed an eternity under fire. This continued and I tried also to stay near the southerly path, even at risk of improving their attack angle. If I didn’t get south a couple hundred miles my goose was cooked, anyway. Due to their inflexibility, I was able to help by turning slightly into them and climbing toward them at the start of each pass to increase angle-off and gain cruise altitude, then to readjust toward the south. As one started his pass, my fear turned to desperate fury, and I emptied 1800 rounds in one burst after he passed me, although it was futile since roll rate prevented me from sighting on him until well out of range. I remember the 50 caliber tracers tumbling out of my gun- barrels before the last round of 1800 was fired, non-stop from all six guns. I guess the MIGs were in fuel trouble also, but I prefer to think they scrambled out of the way of that crazy American. My blessing was that I must have encountered the four lousiest gunners in the world. I didn’t know how far I had to go or how far I could fly in a situation I had never faced before. I climbed to altitude, then cruise-climbed higher, hoping I would have enough glide to make it across the ground combat line into safe territory for bail-out, better yet home. Our base was not very far below that line. I shut down the engine with barely a few gallons left to get the best chance. The first time I was ever gliding a powerless jet, since my flameout in the F-80 in advanced training as a Cadet. I was able to glide directly home to K-14, starting the engine on final, just in case I needed it, plus avoiding embarrassment of being towed off the runway. Everyone had long since landed and Hoot later said they had already written me off. Maj. Winton W. “Bones” Marshall, the 335th Commander at that time, had unexpectedly flown in from Tokyo. He climbed the ladder to greet me, one of the endearments he offered over the years, and we inspected the airplane and found the wing stress plates were severely damaged and the ailerons were physically binding. I would fly many times in the future with Bones, a wonderful guy, who had a sort of Huck Finn quality and was, after all, my first combat squadron commander. I had noted during the return flight that the G meter (re-settable “max g” needle, available only on the “A” model) was pegged, which if memory serves me was 12 g’s and surprised me the airplane could survive at all. It was rebuilt and continued to fly after ailerons and the fuselage stress plates were changed. That event began my use, or abuse of power-off cruise descent, for which I would find myself in a brace facing a pissed off general, almost seven years later. Hoot’s victory, on that mission, made him the 3rd jet ace, when Captain Richard Becker beat him to it by a few minutes, as verified later by the radio transmissions. That was the highlight of my flying experience to that point and, although I was more afraid during the chase than ever before or since, I gained in the knowledge that I was pretty unflappable and knew I could handle whatever came along in the north after that. I found that the risks of combat put an edge on my skills that was satisfying and built confidence.

We lived in tents, and nights began to get cold. Soon the winter artic air would arrive from China. There was a nighttime air raid on occasion by a small North Korean utility aircraft flown by “Bed-check Charlie” who dropped explosives on the base. One night the sirens sounded, so we were sauntering to the ditches, when we heard his engine wind up as he climbed away from his silent, powerless glide and rounds hit just as we reached cover. The only damage was to one of the tents, where there were minor shrapnel holes, except to a clothes stand of one of the jocks. Every garment he had hanging on the rack had at least one tear in it. Sewing added to the income of one of the Mama Sans, who waited outside the base barbed wire fence to do our laundry with rocks in a nearby-stream. Charlie, typically hit and ran, but the alert maintained for a while. Then the sound of a B-26 returning home, across the base, could be clearly heard and his navigation night-lights were bright as he flew down the runway slowly at 1000 feet, prepared for landing from his mission. As he started his turn to landing approach, a huge spotlight illuminated him suddenly, from the Army’s anti-aircraft batteries surrounding the base. Then a second light and a quad 50-calibre AA gun let go, with trails of tracer rounds tracking the airplane. All hell broke out around us and there was firing from every quarter toward those poor fellows, with heavy AAA added. I watched in horror and didn’t give them a chance. They turned out their lights and headed toward Seoul but the AAA didn’t cease until they were well out of range. In their haste they over-flew another position in the distance and took a second barrage. Miraculously, the aircraft went unscathed.

The life was exciting and made more pleasant because Martha was visiting the aunt and uncle that raised me and they took a couple of photos of her near the bird-bath in our old back yard. It was not just the nostalgia, which I truly enjoyed and treasured. They were especially pleasing considering that she had Bobby less than six month before, but she was overweight if she reached 105 until her 60’s, when the standard was lifted a bit The enemy was unpredictable. We flew a lot of missions when there were no MIGs or they chose to fly above us, out of reach. In that early period the MIGs seemed to be in training above us in large groups but often unwilling to fight, ... then suddenly attacked, followed by a short run back to China. Finally, they would stay and fight more regularly, and then the cycle would begin again. We rationalized that a ‘New Class’ had arrived. They seldom got too far from their border, where we flew a race track with four flights spread over the western length of the China/Korea border, waiting for them. They knew we were the only threat they faced, as the only Sabre wing in the Orient. Later, we faced airplanes with different colors than the red nosed Chinese and more aggressive pilots. We surmised it was Russians and other Europeans, which was confirmed after the war. In fact, Russians pilots scored the majority of F-86 kills. Col. Herman Schmid, whom I never saw, was replaced as 4th Wing Commander by Col. Harrison Thyng, who became an ace during WW II, first flying with the R.A.F. and later an American unit. He was the first Army Air Force pilot to shoot down a FW-190, which he did in late 1942. He would follow that feat with five MIG-15s. Our Vice Commander was Col “Gabby” Gabreski, who later moved to K-13, Suwon, as Wing Commander, and formed the second F-86 Wing. Shortly after my arrival, Gabby flew the first F-86E to arrive on base in simulated combat over the field against an F-86A and whipped the other guy badly, with every Sabre jock on the base as witness. After he landed he briefed all pilots and announced that the limited number of E’s would be reserved for flight leaders. I never forgot his response, when someone asked about the problem of wingmen staying with leaders. He replied “Wingmen are to absorb firepower” and I never knew him well enough to judge whether he had a dry sense of humor, but he made the right choice.

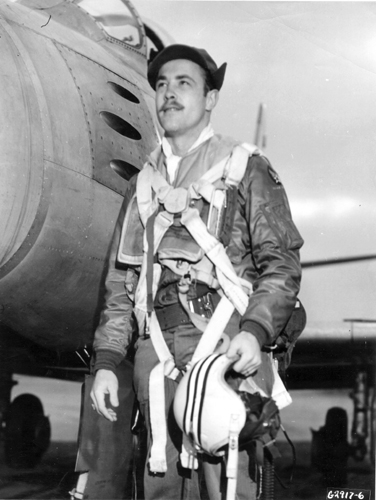

One thing I know for sure, Gabby proved himself the greatest at our skills and talents, when he added 6 ½ MIG kills to his 28 victories in WW II and become the all-time American Fighter Ace, and I MIGht add, he did it in the P-47, not the better air-to-air P-51. And he didn’t have a chance to fly the much more powerful F-86F, which arrived after us. Gabby passed away recently. He was the father-in-law of my dear friend, B/G Alonzo “Lon” Walter Jr., himself an F-86 jock in the Korean war, flying at the start with the 4th, then in the more hazardous air-to-ground attacks in the F-86F. Lon’s daughter was recently promoted to Air Force Major General, and is married to Gabby’s son, a retired Air Force pilot, and gave that great hero a grandchild, before he passed on. Col. Royal Baker was the 4th Group Commander, who stayed on until March 1953 and ended with a score of 12 MIGs and one LA-9, added to his 13 WW II aerial victories. The MIGs were always coming to us from above, a great advantage and he decided to try a change of tactics on one mission when we had a few more F-86E airplanes. The E did not provide significant added power but, with hydraulic flight controls and a full-motion stabilator it turned much better at high Mach number, and its new wing slats were more effective for speed at altitude when turning. He decided we would climb to our highest altitude and surprise the MIGs, by catching them below us. I had an “A” model and with our external tanks I could not keep up with the flight from my number four spot. Turns in any direction reduced my airspeed, with no chance to accelerate. Turns into a wingman gave him some advantage in cutting corners but the locked slats of the A model lost more than gained in that trade. Turns away really but me far behind. I began to feel mighty naked dropping back, but would not abort, so I tried an experiment; sort of last resort. We had an emergency fuel pump for failures of the primary so I figured two were better than one. I engaged the second pump, which was not for this purpose, but it supplemented fuel pressure and drove the engine rpm above the maximum military power to about 102½ %. I must say my butt was puckered, wondering what the result would be when I engaged that switch, sitting near the Chinese border and hundreds of miles from friendly lines, but pride is consuming. We learned just how high MIGs could fly. The MIGs always came in well above us, and they also did this time, and we had to drop our tanks and gain speed to minimize their advantage in the ensuing attack. This was our first and last attempt to gain altitude superiority After a while I grew used to the large gaggles of MIGs above us in the contrails. The first time the odds seemed shocking, but as time went on, I pondered a sense of superiority in being outnumbered because, once in a fight, most airplanes we saw would be bandits, while the enemy must have been busy chasing each other a lot. Meanwhile, I was busy starting to develop what I hoped would be a sign of maturity, a handlebar moustache.

The F-86E began slowly replacing the A’s. I was allowed to fly combat the rest of this first month and logged 16 combat missions in the ‘A’ and a local checkout in the “E”. By tours end we had mostly E models and I had flown 31 of my 100 missions in the “E” model. I was lucky to get above my allotment of 10 combat missions before going back to Johnson A.B. to join the 335th, my squadron but the picnic ended for me and I had to hop back to Tokyo a while, until all three squadrons were reunited at Kimpo. We rejoined just in time for conversion from tents into reconditioned Japanese WW II barracks, which were like heaven with winter upon us. Except on certain windy days, when our kerosene space heaters backfired and everything we owned and slept in was covered with black soot, and no vacuum equipment for clean up! Such incidences were exacerbated by the fact that the only water we would see was from altitude or to drink except for the lucky guys who were on Rest and Recuperation in Japan for a few days. Shortly the only white guys were those that just returned from Tokyo, the rest were dusty brown, except for Rags. He stood apart from us only in one thing, when he inverted our favorite exclamation to: “I can’t wait to get a black girl on white sheets!” With spring would come reopening of the water barrel shower system across base. The biggest plus for me early on this assignment was that my friend and classmate John Honaker by the greatest of good fortune, not only joined the 335th squadron, but our flight, as well. I missed John in the brief period we separated and it was a great boost in our morale to be together. John was the kind of person who would be a friend for life. He was a fine husband to “Bunny” and great father for his three children and he defined loyalty. His companionship just added another dimension to my happiness for the situation, except for the never-ending loneliness for Martha, Lane and baby Bobby When another F-86 Wing was moved to Korea, at Suwon (K-13) not very far south of us, Royal Baker moved into Wing Vice C.O. and Col. Harrison Thyng, replaced him as Group C.O. Col. Thyng added 5 MIGs to his score of 5 victories in WW II before his assignment was completed. When Col. Gabreski moved to Suwon, he took with him a couple of 4th Wing pilots, one of whom was our squadron’s Lt. Iven Kincheloe, who subsequently achieved ace with 5 kills while at Suwon. Soon, John Honaker and I received a pleasant surprise with the arrival and assignment of Billy Dobbs to our squadron. Unfortunately, D Flight was full and E needed him, a circumstance that I regretted personally and suffered from professionally. Oh, how I wished to have Billy as a wingman because he had the best pair of eyes I ever witnessed when it came to spotting an airplane in the distance. That was a capability that I noticeably lacked and the primary weapon for every great ace. Billy was handsome, and somewhat reserved compared to many of us, but was gaining confidence, and like John Honaker, Billy had a sort of bashful quality. Flying had been our only real pastime in Rome and I can’t remember him dating or talking about a girl back home. As a matter of fact, when I heard of Billy after his return to the states, I was surprised to learn he had married a childhood sweetheart, so his quiet demeanor had hidden his more serious thoughts.

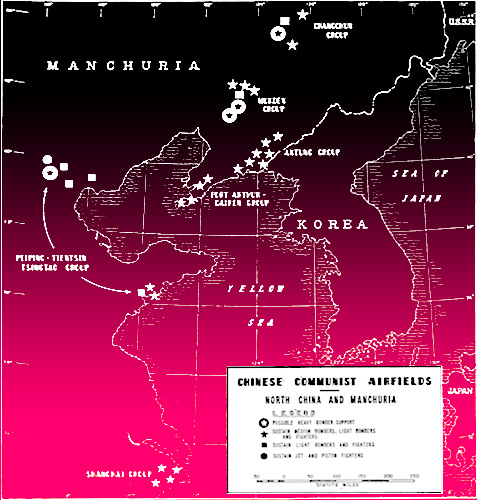

Two Flight Leaders with us at that early time, who later became 335th Aces, were Captains Bob Latshaw who got 5 MIGs and Conrad Mattson added 4 MIGs to one WW II victory, both made their kills after my departure. The Communist Combine, of China, Russia and East Europeans were clearly expanding rapidly. They already had 455 MIG-15’s, not to mention a large number of reciprocating engine fighters and bombers in Southern China and North Korea. They proved capable of sending as many as 100 on missions. We sent 16 to respond and did quite well, before the addition of the second wing doubled our strength, but we never consolidated formations in combat while I was there. Until then the Far East Air Force (FEAF) had a total of 89 F-86A aircraft, of which only 44 were located in the combat zone, all at K-14. For a period we were struggling with shortage of wing fuel tanks, until some cheap but effective replacements started arriving. Most Sabres remained in the U.S. as our primary Air Defense against a definite threat of Russian strategic nuclear attack at home, which was exacerbated by the war in Korea. The road and rail interdictions, which were frequently flown north to the border of China were flown by F-80 and F-84 jet fighter-bombers but were forced by the growing Chinese numbers to move further south toward Pyongyang the capitol of NK. Even more endangered were the daylight photo recon flights all the way to the border by unarmed RF-80’s. We would send a pair of F-86’s to protect them, on excursions far north. The air war was picking up. In April and May, 59 attack aircraft, including P-51’s, were lost to ground fire and 22 the following month. The loss of 82 in just 3 months put the contributions of those less sung heroes in perspective. I would learn years later that air-to-ground was less touted but more demanding in many ways, and courage above all. Night was the working time for any number of aircraft from old Gooney Birds and light bombers, like B-26s, to the B-29 Superfort, bombers. It was deemed imperative that our capabilities be increased so that the enemy would be less capable of incursions into the south. That began impinging directly on the 4th wing. The 4-engine B-29 bombers of WW II had been flying night missions into North Vietnam, but in an effort to limit the growth of the communist air strength, a typical night raid on one airfield resulted in only 24 craters on the extreme end of the field from 278 bombs. The Communist combines, of China, Russia and East Europeans were clearly expanding rapidly. Three months after they achieved 455 MIG-15’s, not to mention a large number of reciprocating engine fighters and bombers in Southern China and North Korea, they proved capable of sending as many as 100 on missions, repeatedly. The Far East Air Force (FEAF) continued with only 44 Sabres located in the combat zone. Three months later the MIG’s had grown to 525. Addition of the Sabrejet wing at Suwon, under Gabby Gabreski doubled our force, by early ’52. Our own fighter-bomber jets were suffering more losses, while the MIGs were prepared for risk, too, losing 24 aircraft in the first 12 days that month.

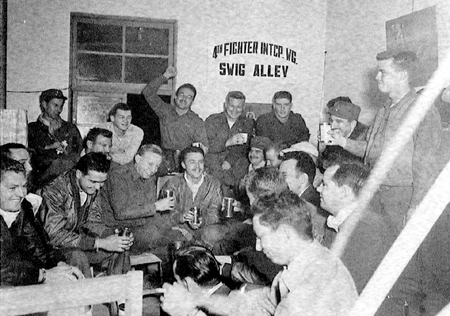

A few of the B-29s had Shoran (short range air navigation) a system capable of guiding bombers to targets from long distance but with far less accuracy than visual sight, about 485 feet, circular error probability. It was quickly learned that the inaccuracy in maps was an additional major problem with Shoran accuracy. By that time the Chinese had two operational and were also constructing 3 new airports just north of the Yalu River along with one operational on the Korean side with 2 more under construction there. Brig. General Joe Kelly commander of FEAF Bomber Command, decided he had no choice but daylight bombing. The first attack was a complete surprise to the enemy and no MIGs showed, but that was not to last. The immediate results were good on one of the first daylight attacks, near Sinanju, NK with 306 X 100 pound bombs landing on the runway. I would later observe in Vietnam that 500-pound bombs did little more than pock concrete runways until dirt fills made them reusable, even for more modern replacements of the MIG-15. However 100-pound bomb would readily destroy an airplane, but dispersal countered that. The job of the F-86 was to attempt to screen the bombers by getting between them and home for the MIG’s but we had the disadvantage of being unable to keep them from flying over us, as much as 5000 feet higher than we could fly. In a sense this took pressure off the MIG pilots because the 29’s were flying twice a day causing our entire effort to turn from aggressive alley cats to defenders of the indefensible. At first the bombers were escorted by straight wing F-84’s and the ancient British Meteors flown by an Australian squadron at Kimpo. Any fighter was greatly disadvantaged in trying to protect the bombers, especially when outperformed by the attacking fighters. It was never practical to stop a determined attack on a bomber from above, and the MIG was designed by the Russian especially for that specific role, with its altitude advantage and killer cannons, if attacked by our Strategic Air Command. In that brief period bomber losses were horrendous, especially in personnel, to the extent that our fighter losses seemed almost incidental, and the Meteors were cannon fodder against the MIGs. Finally, the Aussies had to settle for close air support, no picnic, but not suicide. In one battle, on 23 October over Namsi airport NK, 100 MIGs engaged 34 Sabres from all sides. Meanwhile, 50 more MIGs circled the bombers and tried to drive off the F-84’s, unsuccessfully. Only one flight of MIGs broke through to the 8 B-29’. Just as the bombers began their runs, more MIGs bored in to attack. The lead bomber was raked and on fire, but the pilot, Capt. Thomas Shields, held on through bomb release. The other seven crews were equally persistent to their duty while under severe attack. In the confusion, there was little chance of protection for them. One flight of MIGs came straight up under the bombers attacking at will. Captain Shields, miraculously, flew his bomber and its crew, back to the coast, where all but the captain were able to bail out. Captain Shields stuck with his mortally wounded airplane and sacrificed himself to save his crew. The other two flights each lost another bomber and their entire crews, in that battle, which, from start to finish, lasted less than 15 minutes. Of the remaining four surviving bombers, four returned with great damage to airplanes and crewmen, many dead or critically injured. As for the enemy, F-86’s got two, an F-84 downed another one, and B-29 gunners three. But this was a great victory at a low price to the Chinese Air Force. The following day the B-29’s were persistently pursued after their attack, unusually far south. One crew of eight safely bailed out over Wonsan. After a two-day stand-down, our bombers returned to attack a railroad bridge at Sinanju, and were encountered by 95 MIGs. This seemed suicidal after the prior event, since there, the MIG’s were only minutes away from a dash to the sanctuary of their homeland, to which we were forbidden, at threat of courts-martial. But the bombers ingress and exit over the ocean took advantage of MIG pilots being less aggressive over the water, with only one Superfort severely damaged and 3 with lesser damage. Shortly thereafter, strategic daylight bombing ended, wisely I would conclude. Henceforth the bombers were all modified for Shoran bombing at night, but the trials of the notorious, but outdated B-29 reciprocating-engine bomber, and its crews, who faced some of the most dangerous aerial missions of the war, didn’t end there. The enemy continued to work against the success of unescorted night bombing. Sightings of night fighters increased from 17 in April to 50, in May of 1952. Finally, on the moonlit night of 10 June, when four B-29s of the 19th Bomb Group were sent on a shoran mission to a railroad bridge, the Reds’ night defenses came alive at the south edge of MIG Alley. Searchlights locked on the bombers and maintained them in illumination. One aircraft appeared above to track them, probably the MIGs’ spotter. The helpless formation, were attacked by more than a dozen jets. One B-29 exploded over the target, a second was lost somewhere over NK and a third was so badly damaged that it barely made it to emergency landing at Kimpo. The fourth bomber, last over the target broke the lights’ tracking and escaped. I did not fly on any of those daylight escort missions, having been reassigned to Johnson after my 16th combat mission on 30 September, awaiting our permanent return to K-14. I was again in combat on 9 October, after only a few local training flights in Japan. Just the sight of the mauled and bloody B-29s on the ramp was enough to convince me that those B-29 crewmen were the best example of the spirit and courage of Americans that I ever have seen. In my eyes their combat missions made ours look like a walk in the park, because we were never totally defenseless, a situation they faced every moment. I was happy to be “home” at Kimpo. That month long stand-down from combat was terribly boring, after my exciting beginning, and extended my tour away from home. I would be flying with Bones Marshall and my own squadron, thereafter. Bones treated me very well, as I gained experience, and I flew his wing or element leader on a number of missions. He designated me Assistant Operations Officer of the squadron, under Capt. Cleve Malone, to replace Iven Kincheloe when “kinch” was transferred to K-13. Cleve had been one of our mates in the 27th squadron, at Rome. Shortly after I returned, a most unusual mission fell to us. It was common for our senior officers to lead the wing formation at that juncture, but unusual to have Top Brass leading all 4 flights of the mission, but this was to be no ordinary combat mission, and our four flight leaders were squadron C.O., and up! That mission has become nostalgic for me in another way. It was the last time that John Honaker, Billy Dobbs and I would ever fly in the same flight together; something we enjoyed so much in the past. Bones had selected John as his wingman, and I as his element lead and Billy as my wingman, just like so many times in New York. The three of us were in hog heaven once again, and it wasn’t a dark, cloudy night in Georgia. We knew we were involved in something special at the mission briefing. A flight of enemy bombers would attack the American radar site on Chodo Island, just off the west coast of North Vietnam, near China, with an exact time given. That information and the 4th Wings’ special reaction to it made the mission a success. Instead of individual take-offs on our narrow runway we all taxied to the runway together and took off by fours at a precise time. Radio silence was imposed. We didn’t fly the usual and direct northerly flight to MIG Alley, nor climb to altitude to conserve fuel. Instead, we took a circuitous route climbing northeast to the eastern mountain ridge to hide in ground clutter. We stayed below 15,000 feet, putting us in a low fuel state at our target point. The enemy was expected to come south to bomb at a few thousand feet. Wing tactics at that early stage of the war were conservative keeping the 4-ship flight intact, unless attacked and forced to break off in pairs. For this particular mission, led by Group C.O. Royal Baker, the Wing orders were even more restrictive in that only flight leaders were to be shooters, period! No second runs, due to fuel: one run and a direct climb toward home. As we turned west from the mountains and began our descending run toward the target area, a gaggle of MIGs in contrails flew across our path, south, toward Pyongyang at very high altitude. They had obviously been sent to protect their bombers and our stealth worked. Bones completed his successful firing pass, getting a bomber, with us in trail when one of the LA-9’s, a small WW II vintage fighter, hit him with a head on burst from its cannons. John Honaker, right behind Bones, got off a snap shot at the fighter and blew it to shreds, accentuating the difference between aircraft gasoline and jet fuel, under fire. That was a wonderful sight for Billy and me, as our only authorized assignment was to follow in trail. As we began our climb for home it was obvious that Bones was in a real bad situation. His canopy had been blown off, he was exposed to the winter cold and we had to climb to very high altitude in order to make it to safety. I feared he could not possibly stand that cold, especially since, as his nickname implied, he had not one once of fat on his body. What I didn’t count on was just how tough he is, which he proved again recently by surviving, in his 80’s, an extremely vicious mugging near his home in Hawaii. Bones not only made it to base safely and saved the airplane, but he attended debriefing. Although we had mission whiskey available, it was seldom used by us, contrary to assumptions, but this was the exception. Bones drank an entire bottle over a period of maybe an hour, without any outward effects. His survival was amazing, no frostbite, that was a miracle. The final score against the enemy was 8 TU-2 bombers and 3 LA-9 fighters destroyed. I think that none would have survived with the confidence our leaders would gain and latitude we soon would be granted. We were creatures of our indoctrination, but the score might have been 12 TU plus 16 LA, if all of us had been allowed to shoot on the attack. John had latitude to shoot in order to protect his leader, and he got one, with an excellent shot. Major Davis, 34th C.O. did things his way, in spite of orders. He got 3 bombers, obviously not on a single pass, then managed to slip over toward Pyongyang and destroyed a MIG-15 on the way home. He was known to be a great gunner, and had that very unique vision of the great aces to visually acquire aircraft at long distance, which became apparent in reviewing some of his encounters. He would seemingly head off, out of the area of conflict and find a victim that he had probably spotted far off, before leaving Shortly after that, NBC sent their prime international TV reporter, Bob Pierpont to Kimpo. He chose the 335th for his program on Sabrejets versus MIGs, and specifically John Honaker, because he was the only junior birdman with a kill. Even so, John was the old man of the junior officers, just barely getting under the 26-year age limit out of Cadets. After he completed filming, Mr. Pierpont threw a squadron party for us. The photo of that party in “D Flight” quarters in the barrack, with Pierpont is my treasure. Not only was I with my best Buds, John and Billy, but Jim Kasler was standing near a window beside Conrad Mattson and Bob Latshaw, and all three became Aces. Bob Ronca and I would fly together in flight test and he later flew F-100 combat in Vietnam, for which he posthumously received the Air Force Cross. No flight, good booze, we drank heartily? No, excessively!

In the photo, Bob Pierpont sits 3rd from left, front row, with me on his left, Billy on his right and John obscured by another pilot, on Billy’s left. Soon to be aces, Jim Kasler is in front of window and Conrad Mattson on his left. Bob Ronca, with face almost hidden by beer of pilot standing on far right, would become a dear friend in my next assignment and a hero in death in Vietnam. We really let go in that party because the Weather Officer assured a cold front coming down over China would sock the MIGs in the next morning. Bad forecast, worse decision! I was awakened early with a heavy head and a light stomach, and with clear weather awaiting us in MIG Alley. I recall a bit of pain and illness upon arising and was never so happy about anything in my life as I was with the decision of the enemy to stay on the ground that day and leave us to fly in peace along the Yalu River. |

| next section |