Chapter 4 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

|

Chapter 4 - Approach to Space click on the links below for more of the story... i. Test Pilots & Operations - ii. Experimental Testing - iii. F5-A Freedom Fighter - iv. Variable Dynamics - NF-101A - v. Anchors Aweigh - vi. Two Strakes - One Strike! - vii. Whirlybirds, Spinning Wings? - viii. The Rest of the Story |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Experimental Testing

Upon graduation from ARPS, I was assigned to the Flight Test Center along with four classmates: Don Sorlie, who became Chief of Fighters, Ted Twinting, Al Crews and I with them and Charlie Bock went to bombers. It was a bit of old times since Kirk Wimberly and Joe Schiele, friends and mates from my 1957 class of the Test Pilot School, were there in bomber/cargo test.

This was the place I had hoped to be when I graduated from TPS. Edwards had a history of astounding proportions. Books have been written on that base and some of the greatest names in the history of flight worked, flew, played and died there. Operational jets got their start there with the XP-59, America’s first.

The decade of the ‘50s was certainly a golden one for flight testing, because America’s military were in a race with the USSR for superiority in the sky, while at the same time aircraft engineering and design was making quantum leaps in aerodynamics and propulsion. X-planes were being built, one by one.

Each was unusual and unique and contributed in some way to the rapid developments in military aviation. Our finest test pilots risked their lives for the advance of aviation, some losing theirs in that cause. But each of those vehicles made significant contribution. The X-2, which took the life of one of its pilots, set the stage for the X-15, which became the most successful and prolific test aircraft in history. The sleek looking long-nosed X-3 didn’t accomplish what was intended being underpowered due to poor engine performance, but it proved the cause of failure in an early test of our first supersonic fighter, F-100. The tiny X-4 proved the capability to fly without a tail section, at the cost of life to its test pilot in a spin from which there was no recovery, but that initiated a stream of tail-less bombers by Northup Aircraft, technology that applies even today to their B-2 Stealth bomber. And the X-5 proved the concept of swept wing and swing-wing fighters and provided data on wing sweep performance in the range of 20 to 60 degrees, later employed, either fixed and variable, on many future aircraft.

There was greater risk when the digital computer was not available to predict stability problems. There were lots of examples of outpacing the knowledge beyond safe boundaries. One of those started with the X-3, stiletto-shaped experimental aircraft that first demonstrated cross-coupling, but was so underpowered due to delays in engine development that it never reached its potential, so its pilots lived. Instead WW II Ace and test pilot George Welch would die expanding the envelop of the F-100 fighter, the first production airplane ever to incur cross-coupling.

Without benefit of the insight from mathematical evaluation by fast computers, that happened even though coupling had been technically understood for years, but data from the X-3 had not been addressed soon enough to anticipate it was becoming a real threat.

New fighters, bombers, cargo and helicopters were emerging from the drawing boards. The jet-powered progeny of the mighty B-36 bomber was another monster that lost its competition with the B-52, which became and remains a mainstay of national defense for decades.

Supersonic speed in flight became routine, made so by Chuck Yeager in the X-1A rocket ship.

The Navy D-558 Skystreak didn’t take long to become the first to reach Mach 1 with a jet engine and ground takeoff, when test pilot Bill Bridgeman climbed in it. Soon, there were a number of other research aircraft doing their part in paving the way for the future, some important, others dismal attempts, but all contributing to the outcome.

The famous century series of supersonic fighters commenced entry into the Air Force inventory, beginning with the F-100 Super Sabre, which was only a rumor when I was in Korea. It and the F101A were tactical fighters. The F-101B and F-102 joined, as the All-weather tandem, the later being the first delta winged airplane.

In short order, the second speed bump in the way of aviation progress was overcome as the F-104 Starfighter and the F-105 Thunderchief fighter bomber took to the skies at twice the speed of sound, Mach 2 in level flight the 105 struggling mightily. Then the F-106 took all-weather interceptors to that regime.

The Republic Aviation Co. F-103 was the most ambitious undertaking of all on paper, but never got past the problems of engine development. It was to have converted from jet to ramjet after take-off. I had toured its mockup at the factory back in 1957, when we graduated test pilot school, and the dual, squared tail pipes of that huge machine looked more like the locks of a dam.

Flying wings seemed briefly to be the wave of the future, moving from props to jets and pursued relentlessly by Northrup, but to little avail until the modern B-2 arrived.

Then the bomber fleet began its surge to catch up to the fighter’s speed. The last great prop driven bomber and the largest, the B-36 with its 6 huge reciprocating engines picked up four additional jet engines before its day passed. The first great all-jet success was the B-47, followed later by the B-52, which continues to provide great service today.

Meanwhile cargo aircraft followed the trend from turbo-prop to jet and spun off into the C-135 and the KC-135 that has become maybe the singularly most vital in our air arsenal, as jet tankers. Then B-58 moved bombers toward the Mach 2 club. Although it never reached the level of importance to defense of its predecessors it had the Cadillac feel of the F-106, unusually responsive and with light stick forces. Like the F-104, the B-58 had significant operational limitations but set a new goal for bomber speed.

Ideas were put to practice, like a little “bumble bee” of a fighter that could attach within the belly of a bomber and drop over enemy territory to protect its host, then reattach to its nest/trapeze for the ride home. That idea like some others never made it past the initial flight stage, but overall, military aviation interest was intensified and progress was stimulated. A jet seaplane fighter and a huge jet seaplane bomber proved their concepts, if not their ability to satisfy the Navy’s need in a big inter-service rivalry. The golden decade also brought a whole group of other strange craft. One turboprop fighter with contra-rotating propellers rested on its tail, nose up and took off and landed from that position, as did a later, similar jet.

As development of operational aircraft continued on pace, a notable advancement was a bomber with Mach 3 cruise capability, the XB-70A. It made its maiden flight on 21 September 1964 in a test I had the pleasure of providing primary safety chase for. Had it not suffered an ignominious fate through no fault of its, but at a cost of two fine test pilot’s lives, it may have had a significant impact on the Air Force operational structure. That project and the accident involving two test pilots deaths will be covered in the next segment of this chapter.

The costs to America were tremendous but in the process the U.S.S.R. was pushed into a race whose costs were too much for their socialistic economy and political failure resulted in the world’s greatest fight between superpowers ending with a bankruptcy, not a war.

Even more recognized than the profiles of the craft were the test pilots’ names and faces, made famous flying them. In the 50’s, the Chief Test Pilots of aircraft companies were atop the news, and negotiated bonus money for test flights, and they got all the early testing jewels. Pilots like Bridgeman, Tony Lavier, Fish Salmon, Bob Hoover, George Welch, Scott Crossfield and “Slick” Goodlin.

Slick became the forgotten one, who first flew the X-1A but walked away from a contract dispute over piloting its first supersonic flight, which made “Chuck Yeager” household words. He did a terrific favor for Chuck when he caused General Al Boyd, himself a test pilot, to select Chuck to fly the X-1A beyond the speed of sound. That not only changed life for Chuck Yeager, it set a precedent for many Air Force test pilots to follow, as we began to get a bigger role in the early testing of new military airplanes. I owe a debt of gratitude for the decision of Slick Goodlin, a man I never met. In the process, he made it possible for me to achieve a record and have some of the most exciting flying of my career, which would not have been likely without him!

This group wasn’t alone among candidates for world’s most accomplished test pilot since all such heroes are time dated, but they were there at the most active period of development. There were many before and many to come, although I believe the power of the computer, electronic sensors and automated weapons tolls the end for man in the loop in the very near future. It would be practical today, in fact.

But before guys get too smug, one author claims a woman pilot, Jackie Cochran set more women’s world records than those set by any one man. I wonder if Ms. Burk, President of National Organization of Women, would have objected to Jackie and the ladies having their own category of records. If so, Hootie Johnson could rest easier as President of Augusta National!

Before I leave the experimental airplane history, the Air Force X-2 pilots deserve recognition, including Pete Everest and Mel Apt. Mel, antithesis of Pete, was an unassuming gentleman, who flew to his death in that aircraft, which had no provision for practical escape from serious trouble.

The grandest X-Bird of all was the X-15. Its pilots set records for altitude and speed by air-launched vehicles that have lasted for decades and how much longer? It flew far more total flights than any other experimental airplane in history and made the greatest forward leaps in performance of speed, Mach number, dynamic pressure and altitude of any aircraft in history, with recognition for the Wright Flyer.

There were too many pilots of the X-15 for my memory, but Bob Rushworth flew it far more than anyone else. Pete Knight established the current world speed record and Mike Adams my Cajun buddy, died in it. In the end, the most famous of all its pilots was Neil Armstrong, whose X-15 experience was almost disastrous, but who put his name in history when he became the first man to walk on the moon. And Joe Walker, the chief NASA pilot established the existing altitude record for air-launched aircraft, more than 50 miles, but Joe would perish flying in formation with an experimental bomber for publicity photos of the aircraft.

When I look back at my own‘ flight log’ for this period it includes a Who’s Who of test pilots; some that I happened to draw for check-outs, currency updates, proficiency checks and instruments checks, and others with whom I hung out at work or took on in backgammon. Tommy Benefield, B-1A test pilot, who gave his life to test it, which resulted in the B-1B bomber, so important to national security and in recent military campaigns. Tommy gave me the chance to fly one of the biggest aircraft ever built, the C-133.

And there were Al Crews, Dynasoar pilot designee; Bud Evans, N-156 test pilot; Fitz Fulton, back-up to Joe Cotton on the XB-70. Fitz later tested and commanded the modified Boeing 747 that hauls Space Shuttles on its back; Jerry Gentry, M-2 lifting body, noted for a surviving an unplanned barrel roll still on tether; Phil Neale, my friend, helicopter instructor and next door neighbor who died testing a French helicopter; Jim McDivitt, Gemini/Apollo astronaut who helped to develop the curriculum for the ARPS and moved on to the Gemini and later the Apollo projects.

Russ Rogers, YAT-28 test pilot and as fine a gentleman as I’ve ever known, who died in an emergency bailout from an F-105; Bob Rushworth, X-15 record number of flights; Wendy Shawler; future F-15 Test Director; Ted Twinting, F-4 test pilot and future Center Commander; Bob White, X-15 pilot and Air Force Cross recipient for F-105 Vietnam combat

and Jim Wood, SR-71 test pilot.

And I flew often and learned a lot about multi-engine aircraft from my Test Pilot classmate and life-long friend, Joe Schiele, C-130 and C-141 project test pilot.

Joe, Lillian and their entire family had become so special to us and that was reinforced during that entire assignment. Lillian is no longer with us but we are thankful of the years we had with her. Their youngest, Steve, such a gentle and kind young man died in an auto accident just after surviving an Army tour in Vietnam. Little Joe and Cathy have raised wonderful kids to carry on, her in spite of an unsuccessful, then a successful second heart transplant, at a time when the procedure was quite new and she quite young. Joe remains a dear friend, retired in Vidalia, LA still trying to learn to play a respectable game of golf, but an excellent test pilot.

And there was a string of X-15 pilots with us during that period:

Within a couple of months, I felt like I was back in the saddle with the F-5, the T-37, the T-39, F-100, F-104 and the C-130. Flying different airplanes was a major part of the pleasure of test flying and the Flight Test Center proved to be the best place to do that. The days of freedom to fly any and all aircraft was changed to the extent that we were permitted on a list of 5 at any one time, but the list could be modified. In my time on that tour I added significantly to the final list of 56 military airplanes I had the pleasure of flying in my career, and became proficient in a number of helicopters.

Three years of test flying at Eglin helped get me to the AFFTC, but I began there, like all the new guys, by flying chase for someone else’s program as my apprenticeship in test operations. Two of my office mates in fighter operations were Mike Collins and Joe Engle, both excellent pilots and both destined to become astronauts. Joe was outgoing, confidant and a smooth politician, and Mike, reserved, candid with quite a subtle wit. Those two and I had been among the 11 original Air Force test pilots submitted to NASA for the initial Gemini astronaut group. Air Force wanted final say on which of its pilots got those jobs, but didn’t wanted to miss the chance to get all 11. Fat Chance for that!

Mike and I had moved on to the final nine approved by NASA, but neither of us made the final selection of Borman, McDivitt, Stafford and White. When NASA decided later to make final additions to Gemini, I was over the age and Mike was chosen, flew Gemini and was Command Module Pilot, circling the Moon as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed and walked into history below him. His role was equally critical, I might add and they could not have had a more responsible man to have their lives depend on.

Joe Engle, unknowingly received a favor when he was rejected from any consideration, probably because he was low on the totem in experience at that time. Before long he was assigned as an X-15 pilot, when still a junior tester, which verified his flying talent and demeanor. That assignment gave him experience and recognition necessary to achieve Shuttle astronaut selection years later, and Command the second Shuttle mission.

Shortly after my assignment to fighter test, Joe Engle and I had completed chase of a test and he made a call on a Navy tactical frequency. Two aviators in A-4 fighters accepted a challenge to engage us. We set a rendezvous and made a bounce, when suddenly, the leader called “flame-out”, was unable to get an air-start and had to bail out. He turned out to be the Executive Officer of the Navy squadron at Miramar NAS, who had come off air refueling and forgot to reset his fuel switches in his haste to battle, accounting for the flameout and lack of restart. We watched his successful parachute landing, wave of O.K. then returned to base, since his wingman had him capped until rescued. Joe claimed his aerial victory, U.S. Navy A-4, confirmed.

During that period I flew whenever possible in any airplane available and got our other real live Cajun, Joe Schiele from Vidalia, Louisiana, to instruct me in the C-130. Let me say that “live” may be a bit much because Joe is so laid back. I found the C-130 to be the most versatile cargo airplane I ever flew, confirmed by it’s operationally outlasting the venerable Gooney Bird, C-47. I know that explains why it is still in production, though Georgia Senator Sam Nunn, long-time Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, deserved a lot of credit for support, I dare to guess, what with that airplanes production plant in his state.

One day I encountered Mike Adams, like me, flying an F-100. We started rat racing in a position that put us evenly matched from the start. Mike whipped my ass soundly in that dogfight, and I prided myself on seldom coming out in that position. The only thing that made it feel a little better than terrible was the fact that Mike was such a great guy and a super fighter jock. Mike did no showboating, and showed no ego, but a world of confidence. I can say without qualification that Mike and Joe Schiele were the only quiet and reserved Coon-Ass Cajuns I ever met, and I worked and played in New Orleans for 13 years, in my after-life. I was very pleased when I later heard that Mike had been selected as X-15 pilot but terribly distraught when I learned of his death testing it.

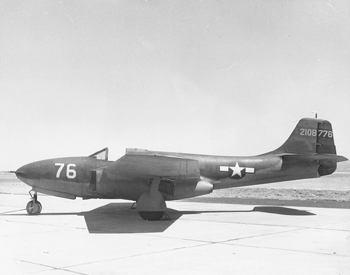

I got my first major test assignment, as the test pilot for the evaluation of the F-5A, Freedom Fighter and made the first flight by a military pilot on March 4, 1963. I was checked out at the Northrup factory near L.A. |

| previous section | next section |