Chapter 4 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

|

Chapter 4 - Approach to Space click on the links below for more of the story... i. Test Pilots & Operations - ii. Experimental Testing - iii. F5-A Freedom Fighter - iv. Variable Dynamics - NF-101A - v. Anchors Aweigh - vi. Two Strakes - One Strike! - vii. Whirlybirds, Spinning Wings? - viii. The Rest of the Story |

|||||

Variable Dynamics - NF-101AOctober of 1963, in addition to starting me on the most unique flying of my life in the rocket powered NF-104A, AeroSpace Trainer, began an unusual learning experience when I flew a very special test aircraft. It was an F-101A, Voodoo fighter jet, which had been modified to test a fly-by-wire control system, designed and built by Martin Company. The system was being developed to control the lifting body design, which was a company area of expertise. Lifting bodies were not inherently stable so it would be necessary to use “fly-by-wire” for high speed reentry flight, a routine approach in today’s technology but not then. Much of that work would play a part in the future of lifting bodies, the Space Shuttle, today’s combat aircraft and even commercial aircraft. To the chagrin of pilots, that will also facilitate the ultimate extinction of aircrews, when coupled with advances in many sensors, weapons and navigations aids.

What was so unique was the pilot could select dynamic stability parameters and time constants to make the controls go from so stable it felt like a conventional bomber to so unstable that it was virtually uncontrollable in a practical sense, even when trying to make a simple flat turn. It could be adjusted to control response from impossible to flyable, just to make a 360 turn without violent porpoise, or loss of control. In the F-101 that was not at all routine because, like the F-104, it had a high horizontal stabilizer and was just waiting for a chance to pitch up and spin, and without friendly spin recovery.

The designers of this experimental tool, of an airplane, were obviously aware of what was in store and had a big “paddle” switch on the control stick that disconnected the system with a touch. If anyone ever flew it without ever hitting this Panic Paddle they didn’t go very far in trying the limits. This kind of opportunity was like being privileged to a look into the future for a pilot and was a flying laboratory for an aeronautical engineer who studied the equations of aircraft stability and control. Suddenly the theory came to life in a real flying machine, for me. I knew of no simulators for that at the time and here it was in a high performance airplane! That was an exceptional learning experience for me, both technically and in flying techniques.

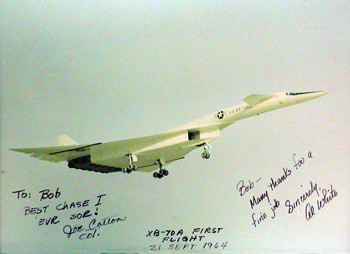

Flying chase was never as exciting as being the tester, but in some cases was very interesting and quite important to the success of the endeavor and the safety of the test pilots. One of real interest was my opportunity to be lead safety chase in an F-104 for the first (21 Sept 1964) test flight of the XB-70, which was flown by Al White, North American test pilot and our own outstanding bomber test pilot Col. Joe Cotton. As chase pilot I learned the systems and anticipated characteristics of the experimental aircraft in order to aid in any emergency in flight, which might require knowledgeable observations.

The XB-70 was a beautiful, white giant cobra, in flight. At very high speeds its wings would provide more lift than necessary but not enough horizontal stabilization. The conversion of lifting area to stability area was brilliant and successful, with large wingtips that could be lowered from horizontal down to 70 degrees to trade unnecessary lift for added stabilizer area, between Mach 1 and Mach 3. It was the only bomber to fly three times faster than sound, and it had no serious difficulties meeting its test objectives and looked like it would become an operational aircraft for Strategic Air Command.

Joe Cotton was noted for his skill and experience in bomber testing and was an extremely fine gentleman and officer, at work and with kids on base, like his son and mine who played baseball on the same team. Joe was beloved by all of the guys in flight test, as well as all the kids. One thing that made life at Edwards so desirable was the close relationships established at such an isolated base, yet with Los Angeles a reasonable commute. Those of us who ‘lived to fly’ were in heaven on earth, and so were most of our families. Even the whistle of the TV antennae guy wires singing to night winds of the high desert gave their own serenity to sleep, once indoctrinated. Because of Joe’s personality, and that of Fitz Fulton, back-up Air Force test pilot on the B-70, I treasure their photo with the white bird equally.

A mid-air collision, no fault of the bomber or its crew, would soon bring this exciting program to an end and cost the life of Carl Cross, one of our nicest and most skilled test pilots and hands down best golfer on the base. It also cost the life of NASA’s X-15 test pilot, Joe Walker, who was piloting the F-104 that collided while flying formation with them. The accident ultimately ruined Joe Cotton’s long and honorable Air Force career, though honestly no fault of his. He was not even flying since Carl was copiloting with Al White, the North American company test pilot, who successfully ejected, unlike Carl who endured a long slow flat spin as the tail surfaces were torn away and then half his wing finally separated to mercifully hasten the inevitable tumble to earth. The B-70, because of its high mach and altitude capabilities had two separate crew compartments, which separately encapsulated the pilots for ejection, in which the pilot rode under parachute to the ground. The flat spin of such a long fuselage put so much centripetal force into the capsule that the hot gases of the ejection sequence could not move the seat for the capsule’s cover to clear Carl’s head, thus the ejection sequence was automatically aborted, leaving no possible escape. There are times in government service when sacrifices are ordained for even the finest, especially when two houses of the U.S. Congress are in full posturing mode for public consumption, as was the case on the notorious XB-70 mid-air crash. The accident was the stuff of newsmongers: the photographers’ airplane was owned by Frank Sinatra; the NASA X-15 pilot was killed; along with Carl Cross. In my next assignment I would face my most onerous and undesirable task of 20 years, being designated the Recorder of the Collateral Board on that accident. That group, separate from the Accident Board was known as the “Hanging Board” Thankfully, being junior to the defendants, I played no role in the determinations, but had very demanding tasks and close enough to feel the pain. Details and accident photos are presented in a later chapter.

Russ Rogers, one of my all-time favorite men, flew the tests on the YAT-28, a modified version of the single radial-engine trainer, which was converted to a turbo-prop with numerous munitions stations also added. The YAT was intended for use in Vietnam, but like many other such kluge-modifications of the era, it was finally abandoned. I found by flying it that it did have some unique capabilities and a great deal of acceleration but the decision to cancel was probably a good one.

Another intended upgrade that I flew was an improved version of the North American B-26, of WW II vintage, capable of cruising at P-51 speeds, but certainly not while carrying it’s expanded myriad weapons on its wings.

There was even a YAT-37, this one a tactical version of the jet-powered primary trainer, with bomb racks and a 7 mm mini-Gatling gun. The fact that I flew these, one-of-a-kind airplanes, added to my enjoying that tour as well as my preparation for experimental testing. I would find later, in my next assignment to Systems Command Headquarters, Office of Limited War, that many contractors helped generals find “pet solutions” to the expanding war in Vietnam, whether it was an airplane, weapon or electronic gizmo. Russ Rogers death in bailout from a F-105 over the Pacific near Okinawa, just a few years later, was especially difficult for me. His wife was a lovely lady and his boy played ball with mine and was an especially wonderful young man. Russ successfully ejected, as witnessed by his wingman, but his parachute went into a spiral, candlestick, and he plunged into the ocean.

One thing was certain, that there was always a stream of important visitors arriving. Edwards never seemed to lack celebrities. President Kennedy visited, also Vice-President Hubert Humphrey, during my tour of duty. Even the Shah of Iran, himself a fighter pilot, dropped by to pilot a F-104 with Instructor Pilot, Jim Wood in back. It was a place where the opportunity for new flying experiences just seemed to pop up. Tommy Benefield, was flying the C-133 in test and gave me the opportunity to fly it with him. It was a huge cargo aircraft. My most memorable recall of handling that giant was its structural flexibility because of its huge size. I was flying it and Tommy said to give it a good roll pulse, meaning a sharp aileron input and immediate release. This has different effects on different airplanes, for example the H-21 chopper would roll completely over into structural failure if you didn’t stop it. But with the monster 133 nothing happened: no response in roll, whatsoever ...... until, suddenly the tail-section of the aircraft made a series of sharp yaws, left-right-left …. it then subsided. The airplane was so long that the torsion introduced into the fuselage was carried aft through the structure in such a way that it reacted as if the rudder, not the ailerons was pulsed. After I left Edwards Tommy became the Air Force test pilot for the B-1A, and like many testers, he perished in an accident while testing.

When I think of Tommy Benefield, I can’t help but recall a basketball league we had a year earlier on base, and our starting team was (clockwise from the trophy) Merv Evenson, Joe Engle, Wendy Shawler Joe Schiele, who played at Louisiana State University and Al Crews, and reserves, such as I, at the grand height of 5’ 7 ½. We were playing the test pilot school team, on which Tommy played at the time. He was a large guy, well above me in height and much stouter. He was aggressive, determined and dedicated to victory. He and I ended up in a jump ball and I had no chance to tip that ball with him towering over me, or so it would seem. But there was only one referee, who would be watching the ball not us, so I grabbed two hands full of Tommy’s shirt at his waist, and pulled down hard, just as we jumped together. I found myself launched above him and easily tapped the ball to our player, as Tommy chased me off the court, in a fit. I had a good head start because I knew what was coming and hit the floor in full retreat.

|

| previous section | next section |