Chapter 2 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

Chapter 2 - Aerial Combat click on the links below for more of the story...

|

||||

|

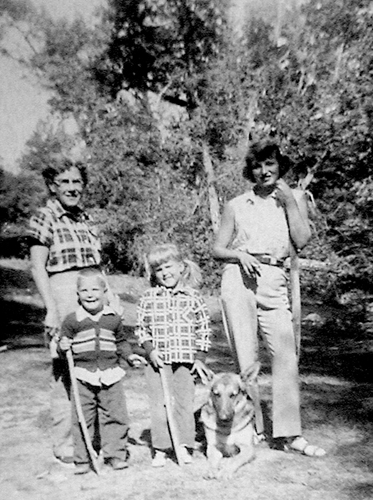

ROLLIN’ WITH BONES 93rd Air Defense Squadron, Albuquerque Municipal Airport, N.M. Apr 1952- Aug ‘53 Major Bones Marshall had returned from Korea to command a fighter squadron at Albuquerque, the 93rd of the Air Defense Command. It was equipped with old F-86A’s. Except for the Air Guard, it was one of the few still equipped with them, but any F-86 beat any other fighter. Martha and our two kids were living with my parents in Albuquerque while I was in Korea. Bones had arranged for my transfer to his squadron, and it worked…It pays to be an Ace …. I arrived to enjoy serving him once again. I flew my last combat sortie 9 April and first flight with the 93rd on 27 May. My other stroke of luck was to be assigned to Flight Leader Kenny Chandler, whose flying prowess made it a privilege. I would never forget the acrobatic maneuver that he and Chuck Yeager flew for the movie, Jet Pilot. The reputation he had earned in the 336th squadron at Kimpo, was first class. One flight on his wing affirmed what I had seen and heard of him. I prided myself on being able to fly excellent formation acrobatics, so I made sure we got around to that on my first flight with him. He was smooth as silk, in any and every acrobatic maneuver, making hanging tight on his wing a breeze. Kenny was beyond doubt the smoothest leader in formation acrobatics that I have flown with, measuring up to an excellent leader, Robbie Robinson, some years later when I had the opportunity to fly with him and the Thunder Bird Team. Ken was so natural that he seemed to be able to do anything without need of practice for proficiency. It was more than just ability, he had some special assurance so he could lay off any facet of flying for a long time, jump into the cockpit and repeat like it was yesterday. He was different than most of the great pilots I’ve met because he was confident but not cocky. From what I later experienced, Chuck Yeager, Kenny’s partner in the movie had that same invincible attitude, but he invented cockiness. I have learned that while Chuck could be aloof at times, Kenny was quiet and unassuming. Our primary duty in the squadron was when on alert 24 hours a day. Our responsibility was to get our alert aircraft airborne within 5 minutes, which we could easily achieve from our special hangar right off the end of the runway. We had 4 birds with crews around the clock so we could use two airplanes for training, with ADC controller approval, which was usually granted. I got to do a lot of flying with Kenny and learned a lot, including how much a smooth leader contributes. The 93rd seemed to go through Operations Officers at a rapid pace. I was there from May 52, to early August 53 and we went from Maj. Alex Sentes to Capt. Harvey McDaniel, Maj. Rex Warden and finally, Capt. Arnold Hector. Actually, flying in the Air Defense role reduced the squadron rapport to a large extent, except four of us who would spend a lot of time together as the gunnery team. Sometimes we would be scrambled to intercept B-36 bombers, which by that time had 6 propellers and 4 J-47 jet engines and they could fly at high altitude. The MIG-15 that I had fought in Korea was clearly superior to our airplane for one purpose, defending against high-flying American strategic bombers. When we would intercept a B-36 coming at us, some of us would make a head on simulated attack, since a turn-around and attack was out of the question. Once I did that against one that was higher than usual and held off on pull-up almost too long. My fighter mushed and I just made it over that huge tail, which must have been 6 stories high. Later, head-on passes were prohibited. They had already ended for me above 20,000 feet, because I almost took that bird out. It wasn’t long before we flew to Yuma AZ to begin the process of sharpening our aerial gunnery. How I could have used more gunnery before Korea, but at this stage it was just great and competitive flying and preparation for whatever the future would hold in store. There was a rotation, between flights so we would fly to Yuma and spend all our time shooting gunnery for a week or so before returning to home base. The Yuma station at that time was little more than a runway with more tents than the few run-down buildings. The town I can’t even recall, except for one cruddy bar, that would make a Biker Bar look like a palace, but it was the only place to hang out and have a beer. Before my tour was well under way, we were notified we would receive F-86D, all-weather airplanes. That was not something fighter pilots looked forward to because of the mundane, lone flying, while peering at a radarscope on the instrument panel. Even the idea of leader and wingman weakened or vanished with that concept. I prepared to go to All-Weather Training School at Moody AFB, GA, to be followed by F-86D school, and there to be converted to a straight and level radar driver. I worked hard to recondition a small old construction trailer, which was offer by a neighbor. I recovered it as junk from a prairie dump, in order to be with the family, so shortly after our long separation. We certainly wouldn’t live high on the hog; not new to us. We departed pulling our temporary home and drove directly to Valdosta, GA, in early December. Production of the new 86-D lagged, and the follow-on school was cancelled. I completed the instrument training, which was great and most valuable to me in the years ahead, and I was back in the cockpit at ABQ in mid-January of ‘54 just 5 days after my last instrument training flight, mostly spent hauling the trailer home. For the next three months I enjoyed the frequent pleasure and challenge of flying air-to-air gunnery against a banner target towed by another airplane. Our aircraft were equipped to ‘drag the flag’ by closing the speed brake on the cable strung full behind on the runway before take-off. That avoided breaking the cable with sudden acceleration of the targets heavy metal pole and bottom weight on the leading edge. Scoring hits on the banner, there can be no doubt as to success or failure, since bullets were painted and every hole could be counted and compared with rounds fired for each of the shooters. We were preparing for a national gunnery meet of the Air Defense Command, between the top scoring teams in the three divisions. The 93rd represented Central U. S. and our individual scoring averages were the only determinant for team selection in the 93rd squadron. I was fortunate to join Bones Marshall, Kenny Chandler and another pilot whose name I cannot recall, as the central team. At that point our gunnery skills were very competitive, all of us capable of shooting above 70% hits on the 6 by 30 foot banner targets. We started flying to Yuma every Sunday, then flew gunnery every day and returned home on Friday evening, during part of February and the entire month of March. Oh, to have that opportunity before going to fly combat. The rules for official competition limited the number of passes per mission and it was vital to shoot all rounds, since all rounds counted from the minute you left the chocks on the parking ramp, even if you aborted take-off. On the other hand the earlier you fired in the pass, to assure fire-out, the more risk of missing the rounds from longer range. During the competition, we scored well and were in the lead at 10,000 feet, altitude. As the altitude was raised our performance was degraded significantly in our F-86A’s and we no longer stood a chance in the end, being opposed by two teams that had F-86E’s with more engine thrust, effective radar-ranging sights and improved, unlocked wing slats. Maybe the following factual account of a different kind of gunnery involving Bones puts another slant on a unique guy. I mentioned it briefly before, but this puts a better slant on it. It was written by Slip Slater who has been Bones’ friend and comrade, since WW II. I believe Slip leaves it to the reader to decide whether the Captain of the ship was so smitten by being watched at his job by a famous ace that he let Bones take the last shot. “Subject: USS Diablo" While Bones and I were in the 23rd Fighter Squadron at Howard Field, CZ, the Executive Officer on the submarine the Diablo invited the two of us to take a four- day cruise and watch how the Navy did their thing. We left on a Monday, sometime during 1966, and headed out to an area to the west of the canal. We had another sub with us, the Conger, and a torpedo retrieve boat which also served as the target. After firing a couple of torpedoes the first day we anchored in some beautiful lagoons in the one of the Pearl Islands. The crew would set up a screen on deck and show movies. It was like a Hollywood movie set, just beautiful! Well the next day back out to sea and more torpedoes. On the last firing, I was down in the forward torpedo room and Bones was up in the control room, where they control the firing. I blame Marshall for this entire incident. Anyway, shortly after the firing and announcement came over the speakers that a torpedo or fast boat was heading in our direction. I could hear it, and then the Skipper orders a crash dive (what in the hell for, I thought we should be going up). Anyway the bloody thing hits between the two periscopes and knocked off a platform that "watches" usually stand on when the sub is surfaced. We leveled off around 100 feet I think, I could hear water gurgling (found out later it was one of the toilets) and could visualize me going up a rope out of an escape hatch. Meanwhile, Bones up in the control room had some water coming in, but you will have to get that story from him. You know over the years how some of these stories vary . . . Anyway it was quite an experience and one Bones and I enjoyed and one he and I love to tell especially after a few drinks. We were briefed, before docking that this incident would be highly classified until released. But, on the way home, we decided to have a cocktail or two to celebrate our survival. When we exited the bar newsboys were yelling, EXTRA, EXTRA, USS Diablo Torpedoed! "Cheers, Slip” Bones Marshall was and still is a very unique man, with a great appreciation of humor and an uncanny determination, probably best proven recently, when he recovered after a brutal beating in a Mall near his home. He has recovered by sheer determination! When I arrived in ABQ we had rented because base housing was not available. After some months, anticipating our first extended tour of duty, we decided to buy our first home, a comfortable 3-bedroom investment, just short of $10,000. The Romero family, Candelario and Elsie, with six kids, our next-door neighbors, became life-long friends, who all still live in the ABQ area. We learned a little about people and prejudice at that time. Candy, of Mexican descent and Elsie, with Castile family lines, were ignored in our Gringo neighborhood, but proved to be as kind and caring neighbors as we have known and that’s a lot, now in our 29th residence. He was ten years my senior, she a bit less. They are still wonderful, now, and they didn’t ever do anything to warrant less in return. They were as American as Apple Pie, with a Nacho accent, mighty proud of it and they didn’t expect to be offered Spanish as a second language. But they got a tremendous chuckle when we tried our hand at it. Candy’s brother-in-law, “Uncle Victor” Sullivan owned a large cattle ranch near Truth or Consequences NM. Victor’s dad, an Irish immigrant had married a local Hispanic lady, and ended up buying a huge adjoined area of land grants over the years. We had great family fun cruising over beautiful cattle ranges in a jeep and riding real working ponies. As we roamed we would sometimes find ourselves far from the homestead at night. Then we would camp out in rustic cabins used by the cowboys during roundups, sometimes choosing the option of bedding down, under the moon. One time, when the weather permitted sleeping outside, just a bit chilly, we were all on the ground with a bonfire. Since we had been away from home too long, Martha and I got amorous, lying so close together on the ground and our extended cuddling awaiting everyone to be sound asleep seemed eternal. Finally, we felt secure, but took great pains to be especially quite and gentle. We were emotionally pleased, and conscientiously proud that we had controlled the situation so expertly. Next morning at breakfast Candy said to Elsie, slyly, “I sure wish you and I were young enough to sleep as soundly as Bob and Martha”, and the ensuing giggles assured us we had been detected. Elsie and Candy were like parents and best friends all wrapped in one, so the embarrassment was short-lived. At the Ranch, the mountains and hills were rough, even for a jeep, especially for an overcrowded one, and I recall Martha once bailed out and climbed on foot, when the mountain got too steep for her. The main house was purely functional, and the Sullivan’s and their one young son, Darrell, were the only residents of ‘Monticello’, where the dirt street was lined with deserted shacks like a ghost town in an old western movie. Martha, deathly afraid of horses, put on the greatest rodeo stunt I’ve seen, when she was finally convinced to ride a real working cow pony, on that dirt road. The horse seemed to sense she was not in control and refused to move after she mounted. Someone suggested she kick his haunches upon which he took a tremendous leap forward with his hindquarter, the typical first step out of the gate in bulldogging. She was holding the reins for dear life and when her head and body flew back and the reins hit the stops, so did that horse. He planted his forelegs and commenced an emergency slide only to have her heave forward and tighten her legs, his signal to jump forward. Miraculously she held on through a series of rapid jump-slides until that pony just quit. That seemed unbelievable, but exactly as it happened. The real cowhands didn’t believe what they saw. Had the pony been offered good traction, Martha would have been the first astronaut! Sounds unreal, but some years later, she was the only person that I have ever seen that never fell down while learning to water ski. She was deathly afraid of the water and she would recover from positions that others would release the rope from fear of a bad fall. Her first submergence, when skiing, happened because our friend, Ed Chaplin, and I decided that it was time and just slowed the speed and made a turn until she slowly sank into the bay, with our shouts of “Watch out for Sharks!” We maintained contact with the Romero’s into the 70’s then lost them. I tried many approaches, even wrote to the Secretary of the Interior under President Regan, a longtime congressman from Corrales NM, attempting to relocate them, without success. He seemed my last resort, and I met him on the House Committee overseeing NASA when I was in charge of the Shuttle External Tank program. The era of the Internet and my finally succumbing to it, brought on a happy telephonic reunion with the Romero’s recently. Buying our home gave us the chance to have a dog, the first for me since I was seven. We chose a beautiful German Shepard pup, that was sired by a Champion, as well as a certified Companion dog, the top obedience rating. Sabre became the squadron mascot, being with me at work, frequently. Because of the 24-hour duty on strip-alert at Kirtland AFB/ Albuquerque Municipal Airport, I began training Sabre, for brief but frequent periods, at 3 months of age. It wasn’t long until I began her checkout in her namesake, the real F-86 SabreJet. Whenever we had to reposition alert to the opposite end of the single runway because of a wind shift, I would sit her in my lap to taxi. It wasn’t long before she outgrew the cockpit, and by that time she reacted perfectly to “Down-stay” and would not deviate, until released. I moved her onto the wing, nearest the tower side, since I couldn’t see her on the swept wing and the tower operators were very attentive of her. She would lie still and never budged, though I doubt she liked the high frequency noise of the idling jet engine next to her. Sabre quickly endeared herself to the squadron, and even with the Air Defense Division HQ, on the base. I recall a meeting called by the Division Commander with Sabre in attendance. She would seldom roam from my side at that time but was not yet unflappable. As the Colonel spoke, a fly passed by her and they were in a real Dog-fight, jumping for the bug and falling back to the floor, from one end of the room to the other. The Colonel didn’t miss a word, but I missed most of them wondering what was in store for me, and Sabre. Not one word of objection was uttered. Sabre had become a pampered celebrity! I was ordered to temporary duty to pick up an 86 in Macon GA and ferry it to Landstuhl Air Base in Germany. I drove Martha and the kids to D.C., to visit my dad and relatives. We were in our used Ford, which was our first auto, since the old Plymouth blew the engine after advanced training. But our new, used car caught fire and was totaled-out. While I was in Germany my dad bought the hulk from the insurance company plus a 4-door, junkyard body to replace the burned hull and put them in the hands of his local mechanic. I returned to drive back to ABQ, after stopping to visit Martha’s family in McKees Rocks, near Pittsburgh. We felt in style in our newly painted family auto, with a door for each of us! In the interim, on 9 June 1953 I picked up, and flew for my first time an F-86F, at Warner-Robbins AFB, GA for a checkout of its modifications. Oh, how I would loved to have had one in Korea, like the guys there at that very time were enjoying. A horrendous tornado had passed directly over that base picking up an auto with mother and child, along with a guard gate and a military policeman. Their bodies and the car were later found. The power of that storm was so vivid that the site from above seemed the result of a giant lawn mower, cutting a swath with defined sidelines, coming in from the woodlands, through the end of a huge warehouse and out the other side of the base. From the air, the warehouse looked like it had been sawed at the edges. From above it was the most dramatic proof of the power of nature I ever have observed. Weather did not always cooperate over the North Atlantic either, even in July. We departed Georgia on the 10th and landed at Bangor, Maine. Our flight of four flew on to Labrador the next day, where we were delayed by weather for a week. During that time I was introduced to the game of bridge. I also got to spend time with a prior squadron mate, Clem Bitner of my first squadron, the 27th. I took great pleasure, and still do, of reestablishing the memory of good times with those friends we shared, so Clem and I had a lot to talk about and enjoy together those few days. The next leg of our trip would be to Bluie West One (BW-1) airbase, in Greenland where the runway began at the edge of a fjord and ended at the base of a very high wall of ice, the leading edge of their huge glacier. Because of the terrain, there was an unusual training routine, very necessary, for anyone flying the first time to BW1. We repeatedly watched aerial movies taken from slow flying aircraft to memorize what we had to do to survive this in a fighter jet. We would be guided by radio beacon to a particular one of many fjords at landfall and begin a journey that involved recognizing every correct turn at intersections of fjords, since all but one path terminated in dead-end. The walls of these crevasses are so high that Dead would be as absolute as End, even in our fighters, since we could fly through at only about 250 knots with the sharp turns, so couldn’t pull up and clear the walls. The dicey situation would not end with the last correct turn toward the base. Because of the glacier’s huge wall directly across the far end of the runway all landings had to be made toward the ice, and take-offs away. Fighters of that era could not clear the wall of ice and the fjord was too tight to safely turn-around, so once into Greenland it was all one-way and only one landing approach, straight in, with no go-around! One last unique procedure was necessary because the runway rose to a big hump at the halfway point. During landings, there was always a person at the far end of the runway, waving a flag on a long pole to give pilots a reference to that point. Prior to that practice blown tires were the result of what appeared like the end of the runway, and a blown tire or any failure meant aborting into the dirt to clear the runway for those to follow. Sounds almost unreal, but that was BW-1. This would be first of our three flights that our so-called poopy-suits were “designed” for. To put the words designed and suit together was a perfect oxymoron. These single layer one-piece rubber monsters with boots permanently attached, had rubber stretch holes only at the neck and wrists, once they were donned, they were water tight, as well as air tight. Those three openings were held slightly open by plastic rings to allow ventilation up to engine start. That was ineffectual as the body temperature rose long before takeoff and any pretence of cooling was gone, with profuse sweat assured. Naturally, it occurred to me long before I saw the first of many icebergs floating in the ocean below that I would freeze to death in my sweaty summer flight suit within minutes with a thin film of rubber between me and the ice water, should I lose engine power. For brief moments in flight one does hear strange engine sounds but drives them quickly from mind. Furthermore, there was no alternate landing site and no means of rescue, in any event from minutes after crossing the outbound coast for almost two hours before reaching gliding distance from safe ejection altitude over the shore of the destination. It makes one who has flown a couple of hours in that condition get a little better fell of the extended flight of Lindberg. Risk was real and death certain. Clem Bitner had arrived ahead of us and departed a day before we did on his flight to BW-1. We learned upon arrival at the next stop, that his engine failed at altitude approaching their destination and restarts were unsuccessful. He notified the air rescue immediately and they headed to intercept him as he glided toward Greenland delaying bailout over the cold Atlantic until the last possible second. The SA-16 rescue seaplane was on station when he called, and in contact with him but was unable to reach him until he was 15 minutes in the water and Clem had expired from the freezing cold. Our next flight was to Keflavik, Iceland, under similar conditions, except for a normal approach and landing. Iceland, like all of the North Atlantic, had a reputation for sudden weather changes and this leg, like the others, stretched our range to the maximum, eliminating any thought of an alternate destination. This particular leg we had 4 flights of four with about 10 minutes spacing. Weather forecasts were good until we had passed ‘no return’ and then things started to degrade. The final flight landed just before the weather socked in so bad that landing would have been impossible. The thought of blind bailouts over an island surrounded by cold water, in weather when rescue was impossible, would not have been consoling after what had occurred at BW-1. The next leg, which was to Prestwick, Scotland was without incident. It was a highlight of my trip because I knew that my first Flight Commander, Jackson Saunders, was flying Meteor jets with the British Royal Air Force and I had hopes of seeing him. When I landed, I got in contact and he said he would fly up to visit the next morning. The weather was poor so I assumed he would be filing an instrument flight plan, as we must at home. I kept checking with British flight controllers but they had no flight plan, then he arrived. I learned that the British only required control around airports and uncontrolled weather flying was permitted anywhere else since they had no other controlled airspace. It was great to reunite with Jackson Saunders, depressing but nostalgic to reminisce about our friends John Honaker and Billy Dobbs, whom we loved so dearly and lost, and to add the sad news of Clem’s death. It would be more than 10 years before I would see Jackson again, but it was an enduring friendship until his demise many years after I too retired from the Air Force. We arrived at Landstuhl, Germany on the 22nd, again on fumes and with one hell of a thunderstorm over the runway. In the context of our current fighters flying half way around the world and back, non-stop, the idea of mid-air refueling, first successfully performed in the early 1900’s had sure taken a long time to reappear. A pilot of one of the other flights ran out of fuel and had to bail out. I landed in a downpour and aquaplaned, before I knew there was such a thing. I was almost stopped at the end of the runway when the airplane suddenly seemed on ice skates. Braking had no effect so I shut down the engine and barely got it stopped. I was surprised that before the rpm was too low I was able to duplicate an air-start, which I had done in flight only, clear the runway for following aircraft, and taxi in without any further problem. On this first trip to Europe for me, I got a day in Germany and couple in London. A kindly, elder gent recognized me as American and asked to guide me on an historic tour of London. He was a walking history of the city and nation, and showed me such sights that I bought and sometimes reread Winston Churchill’s three-volume History of the English Speaking People. The piece of information that stands out more than anything in those volumes for me was that the British had indoor bath and commode facilities up till 400 BC and upon driving out the Romans, reverted to outhouses until just before WWII. It struck me how fragile man’s culture can be, and how lightly he protects it. I believe that was the greatest concern of the framers of our Constitution, one we have grown to take less seriously with success. It also brings up thoughts of the barbarian invasions of Europe and ties the disastrous attack of 9-11 with such thoughts. The Great Crusades, reversed, is a pretty scary notion? Maybe Nation Building into democracies isn’t such a bad idea after all, and Iraq might be a good place to begin, but one Hell of a challenge.

When we got back home, in addition to enjoying some weekends at the Sullivan Ranch, we discovered Albuquerque was a very pleasant and safe family town and the surroundings offered us, a lot of opportunity for pleasure. Then and for years to follow when on annual leave, my parents and the four of us would spend a weekend camping in rustic style in the Sandoval Mountains, north of ABQ. We would build a couple of lean two’s with evergreen branches, use a shovel and rocks to fashion an old commode seat into a semi-modern convenience and live like royalty roaming the area, and enjoying good food. I never recall encountering another human on any of those outings, yet we always camped near a beautiful mountain stream, so the kids could fish. One night, after the “old folks and young’uns” were asleep Martha and I got a little frisky. We slipped out of our protective abode, and tip toed down near the stream in the altogether. In due time, I slipped and fell into the coldest water I ever recall and Martha couldn’t sleep for hours. Have you ever heard a sadist in a fit of laughter? She was witness to the first True Blue Monty!

The vision of flying into the future, in a F-86D, following straight paths on a radarscope, in all-weather airplanes continued to haunt. I was drawn by the exploits of test pilots, especially Chuck Yeager, and the challenges in store for them flying airplanes and missions that were breaking old boundaries. I had gradually come to the conclusion that I wanted the chance to do that and discovered I was qualified to apply for the Air Force Test Pilot School. I was intrigued with the thought that we were about to enter a new phase of flying machines, especially advanced in technology, where engineering might become more important. There was precedence in either direction set by great test pilots. Jimmie Doolittle, the greatest in my mind, was a graduate of Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a PhD in Aeronautical Engineering. On the other hand, Chuck Yeager had no such education, but without degree had successfully broken the sound barrier and already tested more aircraft than any other pilot that I was aware of. I felt the future would be more in tune with Doolittle’s example and discovered that the Air Force Institute of Technology, if I qualified, would allow me two years of university study and a bachelor degree in engineering, at their Wright Field campus or any number of universities around the country. I was accepted for AFIT campus and began the steps toward a new dream. We sold the house and headed for Dayton, Ohio. Leaving Albuquerque was difficult for Lane and Bobby, because they had both grown used to having the grandparents to give them extra attention and love. By that time Lane had lived about three quarters of her life around them and Bobby most of his, but children are resilient and Air Force kids learned to accept the frequent moves and adjust with unbelievable ease. At the expense of acquiring friends of a lifetime, they learned how to make a lifetime of friends, enjoying each as long as possible. Most proved to be very happy and well adjusted by their experience, especially facing today’s more mobile lifestyles. |

| previous section |