Chapter 2 >

Autobiography home >

NF-104 home

Chapter 2 - Aerial Combat click on the links below for more of the story...

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

ACES ARE BORN: THE EYES HAVE IT! (Part II) 4th Fighter Wing, 335th Squadron, Kimpo AB, Korea: August 1951 - April 1952

The Communists had begun new and more aggressive tactics and a greater willingness to engage. They used coordinated “trains” of MIGs crossing the Yalu River over Antung airdrome in the west and simultaneously with another train to the east over the Sui-ho reservoir. On occasion, they would drop off flights or sections to engage us in our usual tracks just south of China and continue with the mass to Pyongyang to engage us as we would exit, low on fuel. On their way home some would drop below 20,000 to surprise our fighter-bombers. On rare occasion, a section would close from the Sea near Sinuiju in an attempt to tighten the vise. What kept us from being more effective was the decision to remain tied to the traditional “fluid four” flight tactics. For a good part of my tour we were running around with three defenders for every aggressor, among us. This began to change, and one of our squadron commanders was an instigator by his own devices. Major George A. Davis, commanding the 334th was an extremely aggressive and confident pilot, which in the end cost him his life on 10 February 1952. He led eighteen Sabres to shield a fighter-bomber attack on railways near Kunu-ri and saw MIGs high in contrails in the northwest toward the Yalu. He took only his wingman and went there and by climbing caught the MIGs off guard. He descended to 32,000 and shot down two in a short period. As he pulled in, to fire on a third, the number-four pilot scored with a cannon burst that shot down and killed Major Davis He was lost because he elected to penetrate their formation. He risked doing that to assure kills, and he was such a sure shot, but our 50 caliber machine guns could take many rounds and some time to do their work while the 37 mm or two 23 mm cannons of the MIG might be lethal with a single shot. A MIG wingman got such a shot at Major Davis stopping his string at 11 MIGs and 3 TU-2 bombers plus his 7 victories of WW II. He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Amazingly he accomplished his Korean kills in slightly over 3 months, at a time when the MIGs were not at the height of activity they showed later. He also never had the advantage of the much superior F-86F, available after our time. He was clearly one of those pilots with the most necessary and special gift of sighting aircraft at a distance and he possessed the courage to press attacks relentlessly, talent to out fly his quarry and the skill to shoot expertly. His record was broken later by Capt. Joseph C. McConnell, with 16 MIGs, who enjoyed some advantage with the F-86F. Joe, on one of his missions pursued the kills so aggressively, that he ran too low on fuel to fly home and could only make it to the Yellow Sea, where an SA-16 amphibious aircraft rescued him and he returned to complete his tour. He later perished in a test flight at Edwards, AFB, just as our comrade Iven Kinchloe would die. Thirteen days after Davis was lost, our new sister wing, the 51st got it’s first Ace, Maj. Bill Whisner, squadron commander of their 25th squadron. Whisner was in the 94th squadron with us in Rome. Bones Marshall proved himself to be an excellent combat commander. Before he departed, Bones gave me the unusual opportunity for a lieutenant to lead a Wing formation of 16 airplanes on a combat mission. It was not a mission on which the MIGs showed up, which I have always attributed to great Chinese military intelligence! Skeptics or smart-asses might say their bad luck. I recently made a new friend, Slip Slater, as we communicated about Bones being viciously assaulted near his home in Hawaii and his progress during a tenuous recovery. Slip flew with Bones back in WW II, when Bones married Millie, a wonderful lady and skilled pilot, in her own right. She flew numerous military airplanes, heavies and fighters, in the Women’s Air Service Pilots (WASP). In fact, Bones was her C.O. and I figure she began to outrank him at their wedding ceremony.

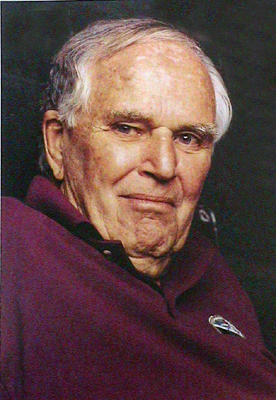

Slip related that he and Bones were together on the U.S.S. Diablo when they were stationed in Panama, when that submarine fired a torpedo, which made a U-turn, and returned to hit itself. Along with his latest recovery from a cruel and severe beating in his 80’s, that tale reaffirmed my long-held belief that Bones is indestructible. Another honor Bones gave me was my own airplane and a great Crew Chief, S/Sgt. Jackson. I named the airplane, Lady Lane, in honor of my 2½ year old, daughter. Bone’s replacement in the 335th was Maj. Zane Amel, a very fine gentleman, who didn’t make a great mark as a pilot, but definitely did by the respect he gave and received from us, as an officer, gentleman and comrade. Operational procedures continued to be conservative until Col. Walker M. “Bud” Mahurin, WW II ace with 24¼ kills including his 3½ MIG-15s, took command of our group. He was fantastic in my eyes because it was patently clear his greatest thrill was to see the young pilots scoring victories. When he wasn’t on a mission he was waving us off, while standing alongside the taxiway. And he would be there on return and celebrate dramatically when pilots signaled success. He had a big impact on results because he caused the basic fighting unit to change from the flight of four to an element of two, doubling our firepower. He encouraged flights to break down to element leaders whenever they felt it gave them an offensive edge, and I don’t have to tell you all the element leaders loved it. We could separate with only an advisory call, to the flight lead. He gave us the confidence that a couple of lieutenants could take on China and it worked

. PHOTO O73, BUD Mahurin WW II Hero and Ace

Sadly, this fine officer and true hero was shot down, became a prisoner of war and was a victim of political correctness before it had a name. He and other POWs were charged with abetting the enemy. Yet, he did exactly what the Intelligence Officers from the States had officially briefed us to do, shortly after I arrived at Kimpo. Although Bud Mahurin was not there at that time, it was stated policy, and for certain it was general knowledge and was never rescinded. We were briefed to tell our captors what they wanted to know or hear to avoid torture, since there was little of importance we could give them. We were encouraged with instructions like. “You know nothing of significance and the free world does not believe what the North Koreans report”. A number of our POW’s, including this superb leader were driven from the service without any benefits for their prior contributions for agreeing to ridiculous lies about poison gases, etc, specific issues that we were briefed to “divulge”, when torture was imposed. Col. Bud Mahurin in spite of being one of our nation’s leading aces, having receiving every medal short of the Congressional Medal of Honor and recognitions from all the WW II allies, was driven to resign from the service, without benefit of retirement opportunity, just four years from eligibility, but the dishonor, for such an honest and honorable man was a travesty. The great man and fine leader that he was assured him success in management in civilian life and he served the military well in that endeavor, in spite of the deceit in politics.

Fifteen years later, through the abuse of Bud, that lesson from Korea was not forgotten in Vietnam. We underwent realistic training to resist pain and psychological torture, by experts, and were mentally and morally dedicated to resist, before posting to Vietnam for combat missions. I like to think I would have held my own had I the misfortune of being shot down over Hanoi in my tour, just as our P.O.W.’s bravely did. But, in Korea, I would have followed official advice as Bud Mahurin did, and felt equally honorable! Shortly after the improvements went into effect, I was wingman for Lt. T. Booth Holker of the 334th when he got his one MIG kill, and I felt wonderful and proud of him. I had been so unusual for junior officers to get a shot. As a wingman I always got a sense of accomplishment without firing a shot, and doing it for another wingman made it that much better.

This new approach changed tactics and attitudes. It made a big change in Billy Dobbs. We seldom had very much radio chatter, unlike the WWII fighter movies hollering back and forth. But Billy and his wingman of ‘E’ flight, Lt. Mike DeArmond, briefly changed that. I recall them in their first scrap with some MIG’s and it was like two radio sportscasters in the middle of a tremendous and competitive game. I could almost visualize the action. The difference was the event was life or death and the final victim was Billy’s first, but not his last air victory. I heard that Billy got four MIGs before he finished his tour. You just didn’t make chatter, for good reason, because so many of us depended on one frequency for critical calls. They took some verbal abuse, but those who knew Billy were pleased with the “Coming Out” of a young hero, whom I knew had the eyes to be an ace. Mike DeArmond was later shot down and confirmed as a POW after I returned to the states, and was repatriated. John Honaker, who had added a MIG-15 to his LA-9 kill, had been designated as maintenance test pilot, as I was. By chance two birds were scheduled at the same time for us. We agreed that after we checked out the Sabres we would do a bit of combat practice, perfectly legitimate, which we had done so many times together in the skies of New York. We sometimes started attacks head-on, but decided this time to take turns starting in trail for the lead to try and shake the other, then trying to gain advantage. I started a hard scissor maneuver with John on my tail and with lots of ‘g’s’. He radioed me in such a way that I just sensed something was wrong. His voice was completely garbled and muffled, as if under far more than normally high-g. I just knew something was wrong! I rolled out, slowed down and turned to find him. Without luck, I began searching for him, making repetitive calls with no response. The tower also could not gain contact with John who seemed to vanish. John Honaker was killed when his airplane impacted in solid rocky hills and Korean witnesses indicated the airplane was completely out of control. He must have hit at very high speed because his’45 automatic, he holstered as we all did, was bent nose to tail. John’s death was unfathomable to me, since we had spent so many hours in flight with far greater risks than what we were practicing in this case. By this time, John and I both had well over 400 hours, a good portion in the Sabre, which we knew so well. It was a terrible way for me to start a necessary hardening process for facing the loss of so many buddies and comrades in the future. Sometimes there’s an escape after a fatal accident to surmise that the other fellow did something wrong or didn’t do something that was possible, leaving the door open to the thought, “I would have found a way!” I had too much respect for and confidence in John to take that way out. Whatever happened to him was beyond correction. Of that, I remain convinced for more than 50 years. As time passed, other fine men joined D Flight . Jim Kasler was one of them. He was a great guy to be around, soft-spoken, intelligent, very easy going with a dry sense of humor. The hit tale was his candid description of his very first sexual encounter when he returned from overseas in a prior time, as a young enlisted man. I will skip the foreplay, to coin a phrase, and jump to the “punch” line, so to speak. She disrobed, he did likewise and due to the newness and excitement he fired prematurely as he approached the target. Sort of a Navel encounter to put it in terms of Sea men. She threw him out! An indication of how much more aggressive the MIGs became later is that Jim, who had quite a few missions when I left, got 6 MIGs in the later course of his 100 missions, so he sure had learned how not to shoot blanks! That didn’t end his combat service…not by a long shot! Jim flew combat in Vietnam, was shot down on 8 August 1966, and remained in prison and under severe and brutal treatment, until the Vietnam POW’s were released in February 1973. He was one of the heroes of that war as combat pilot and prisoner, under extremely dangerous and severe conditions. He owns a golf course, now. How is that for variety in one man’s life? I did my job of wingman well and had helped others score but it was not until my 49th mission that I was credited with damaging a MIG. I had proven myself a reasonably fair gunner in the limited training I had, but it was not until I returned home to train under Bones that I became an excellent one. However, it was eyes, not gunnery, which limited me, as I never missed a shot in Korea even a couple of very long ones. I saw a flight of 4 in a wide-spaced trail turning above. The MIG pilots had a tendency to string out in an extended trail, a bad practice. There was no way I could climb up to them so I stayed level and accelerated turning inside of them toward the leader. I continued this until I actually was way ahead of the last MIG. I was finally able to trade my lead on him for altitude by a pop-up, just long enough to get some pretty good hits on him from below and behind, only briefly as climb and muzzle blast rapidly decelerated my airplane, thus my first score, albeit a weak one. I hoped that would finally get me started and it might have been the end of my handle-bar moustache, though I don’t recall just when I decided to do away with that abomination, trained and tainted by shoe polish, the only available wax. It didn’t set well inside an oxygen mask, or my mouth, where it migrated at times. During this later part of my tour a couple of “retreads” from WW II joined D Flight. Capt. Bob Love was activated from the Air National Guard where he had performed shows as a skilled acrobatic pilot in the F-80. Actress Betty Hutton stopped at Kimpo for an overnight rest and he claimed to have visited with her. Bob could spin a yarn but was a charismatic and handsome guy, so I’ve always believed it. After I returned home Bob got 6 MIGs and became 11th of the 38 aces of Korea.

The other, Capt. Philip Colman, a WWII pilot and reserve officer had been recalled to active duty. He was a baby food salesman before recall and I would bet he sold it by the ton, ‘What a line’! He hitched a flight to our base, got in to see the wing commander and talked his way into our squadron. He reported the “loss of his latest flight records” and told us that he already had checked out in jets. Whatever the case, in his F-86 checkout flight he ran out of fuel on approach for landing, couldn’t make it home, and landed, gear-up, on a small gage Korean railroad track that passed near the base, doing surprisingly little damage to the airplane. His comment I consider a classic: “Only a damned fool would get into such a situation, but once in it, no one could have handled it better!” He arrived as Phil and lived on as “Casey”, in honor of a previous famous Railroader. I doubt that our wing commander was fooled about the jet time and his decision was a good one to give “Phillip” a chance. Because “Casey” went on to increase his 5 WW II kills by 4 MIG-15 kills for a total of 9 victories, a great victory for baby food salesmen all over the world. Maybe the colonel knew about his war record, but our roommate, Phil, never mentioned it to us. I only recently, discovered that in an AFA publication. I recently located him and learned that Casey has retired to live in Augusta, Georgia. I keep expecting to see him talk his way into the Masters Golf Tournament any day now. He might be the guy who can psyche Tiger Woods! He sure could give President Martha Burk, National Organization of Women, some grief in a discussion on the right of women to have an exclusive public national organization, but no such right for a few men golfers. Another unique addition to D Flight was a Capt. James Horowitz, a graduate of West Point and General’s Aide. Some later claimed it was Jim who wrote a best selling novel, under pseudonym, based on our air war with the MIGs. A few who read it thought it disparaged some folks in our squadron, and though he enjoyed irony, I personally did not “see” any of our squadron mates in any of the characters.

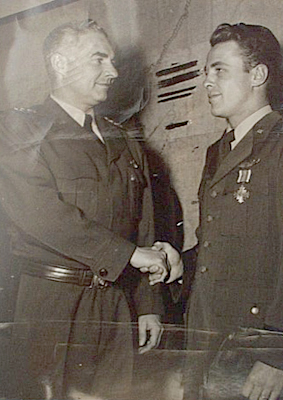

Dogfights began to pick up and I was now flying element lead more often and sometimes flight lead, when I destroyed my first MIG-15 and damaged another on my 74th mission. As usually happened whenever the victim found himself in a very bad position, my victory was almost impossible to lose, and after waiting so long it was exciting, yet anti-climatic. I have remembered watching Hoot’s victory more vividly than my own. He stopped at Kimpo, and while there he presented me the Distinguished Flying Cross in our briefing room at operations.

But the MIGs weren’t scrapping enough to suit us and it was my 85th, before another opportunity was presented. My flight-mate and friend Coy Austin, both in D Flight and at our next assignment in the States, was on my wing and we two escorted an unarmed RF-80, which was doing photo-recce in MIG Alley. We flew along the main supply route north of Sinanju, Korea, near the border with China. I spotted two MIG-15’s preparing to attack our guy and got into position to attack them as they made their attack. We drove them off and I hit the wingman with a burst from long range. He began heavy evasion and I finished him with a couple more bursts. In the process Coy got into position on the leader and he was successful in his kill, also. We then recovered to escort the F-80 to safe distance homeward and returned to attack another flight of MIGs. I got a good shot on number 4 and slowed him down enough to get more hits and had him smoking. It appeared that he was a goner when we were attacked and driven off, not able to confirm the kill. Film study on our return added my ‘Probable’ to that mission. Billy Dobbs had gotten a MIG that same day, with Mike DeArmond on his wing. We were photographed with Casey Colman, who had taken command of D Flight. Photo: New Scan; Bob an 4 others... Per chance, I saw that photo in a very recent article in SabreJet Classics magazine. My only credit was a last name change that certainly has a better ring to it than my own: It was “Smiley”.

Early on, it never seriously occurred to me that I MIGht get even one kill, so the second kill didn’t change my expectations much that late in my tour, and my probable kill adds nothing to status for ace. Looking back, I feel that even with my limited visual acquisition, I MIGht have had a fair chance had I stayed around, for what later proved to be the most prolific period for MIG hunting, a short time later. When I left, there was no sign the enemy would change tactics and no one had ever extended a tour in the Wing, to my knowledge, so that idea never even entered my mind, until years later I was on my 94th mission when I saw a single MIG well below me, racing toward the Chinese border, called my wingman because he was on one of his earliest missions, and started a dive, which would definitely put me right up the MIG’s tail. The MIG was near the limit of my vision so I never took my eyes off of him, for fear he might turn and disappear. I was rapidly closing and descending on him and never would I get a better shot and more certain kill, when suddenly, I caught a glimpse of motion out of the corner of my right eye and, jerking my head right, just as suddenly whizzed past a MIG. It was less than 50 feet away, and the pilot glanced at me as I whizzed passed him, like he was not moving. I had come down so steeply that MIG was hidden until that moment. Instantaneously, he was behind me, out of sight … I reacted ... rolled hard right, heavy g’s, throttle to idle and speed brakes deployed, expecting to end up close behind him for a kill. My mistakes were two-fold, in that decision. I expected him to try and stay on my tail, which was where the situation suddenly put him with such a good opportunity to fire at me. And, I violated a cardinal rule in aerial combat, to never give up airspeed, and there was no faster way than with idle throttle and speed brakes. By the time I saw him again, after my completed roll and tremendous deceleration, I realized he had, instead of trying to shoot at me, turned right and started climbing away for separation, while I lost view of my original “dead pigeon” and squandered my huge advantage. Had I done the correct thing, a loose roll around him trading speed for altitude, I would have had my choice of destroying him, the other guy, or maybe both. I never heard a peep from my wingman, but he was new and besides, it was not his job to do mine! My training experiences were always to try and hang in close in an encounter, with both parties determined to win, cutting the throttle, if necessary to get in trail. Actually, practicing bad habits, but sporting and great fun. Unfortunately, this guy just wanted to get away, which I made possible. I was only able to get a long distance burst into him enough to damage his airplane as he climbed away, and, the other guy, probably his leader, was gone. The concept of energy management in combat training, had not been developed at that time. The career failure, which troubles me more each year of my life, was not making Ace. When you get right down to the nitty-gritty that is what defines a fighter pilot, in spite of the greater risks and emotional challenge of air-to-ground combat. I could fly and shoot very well and had outstanding static eyesight but the eyes of Aces provide acquisition of the moving specks in the distant skies, where the enemy lurks. The real secret to scoring aerial victories is to visually acquire and gain insurmountable surprise and advantage, from afar. When I got home, I went to an eye doctor about my concern, although standard eye tests judged me perfect. I knew, my distance vision was outstanding, but he demonstrated that I had a definite delay in acquiring a focus when I scanned in line of sight, in effect my eyes took split seconds to refocus, limiting 3-D scanning. Not even noticeable in normal situations, but searching for airplanes required a constant scanning, with both distance and azimuth constantly changing, requiring virtually instant refocus. I could never have been a big time Ace, except maybe with Billy on my wing. Nevertheless, 5 kills was a possibility that I blew that day, because with three or four, I may have been offered an extension of my tour. Pride would have kept me there no matter how much I missed family. That day of failure didn’t bother me nearly so much at age 22, as it does today, when I dwell on the impact of my bad decision. Aerial combat demands both control and aggression and I lost control that day, because a full throttle, defensive turn would have made my day a success. It haunts me most, when I think of how close I came to the “Brass Ring”, because of the extent to which the Chinese increased combat engagements soon after I left, in April ’51. The next month, MIGs shot down an F-51, three F-84s and five 86s, but the Sabres destroyed 27 MIGs and 5 other airplanes, and three of my comrades achieved jet Ace, Col. Thyng, Bob Latshaw and Jim Kasler. The fact stands: a fighter pilot hasn’t “done it all’ until he is an Ace. John, Billy and I did pretty well for novices, and collectively were credited with destroying 7 MIG 15’s and one La-9, one MIG Probable and more than 3 MIG’s damaged---- I don’t know the count on damages by John and Billy. We would have happily celebrated that combined score, together, if we ever had the chance, which was not to be after we lost John. Then, Billy Dobbs returned home to his assignment as an instructor at the Fighter Weapons School at Nellis AFB, and married his childhood sweetheart only to be flown into the ground, sitting in the back seat of a T-33 jet trainer, by a student who failed to pull out in time on a ground-strafing run. I will never understand assigning an instructor into the back seat for low angle strafing, where both pilots die if the student misjudges, and the infallible image of the Air Force Weapons School lost some luster. The difference between a perfect run and death is measured in a split second in low angle strafing, with no time for second-guessing, even for the pilot, much less an “instructor” in the back, who cannot dare keep his hand near the controls! The irony of Billy finding the wedding ring on the hand of another young pilot killed in such an accident during strafing such a short time before, when we were shooting gunnery in Florida, has stuck with me all these years. Another melancholy remembrance of that tour is about a young, handsome lieutenant that I met in my brief stint in Hoot Gibson’s flight. I never had news of him after Korea, until I read an article written for the magazine, SabreJet Classics, in the fall of 2001 by my good friend, Alonzo Walter Jr. (B/G Ret’d). That magazine is the primary publication of the F-86 Sabre Pilots Association, one of the biggest organizations of its kind, that in itself is another tribute to the ubiquitous Sabre. I know Lon won’t mind my repeating it in part, beginning at the point of my tour with Hoot, about the young lieutenant, Tom Davis: “Tom Davis continued his progress, and became one of the best wingmen in the outfit. He learned his trade well, even downing a MIG while flying with Hoot Gibson, who later became an ace. When Tom finished his tour, he returned to the Air Defense Command at Griffis AFB, NY, then went to Tyndall AFB, FL in 1954 to fly the F-86D. It was there that he achieved greatness. On a dark night in December, Tom was over the Gulf of Mexico when his cockpit lighted up with the red glow of fire warning lights. Smoke and a loss of power confirmed that this was much more than a malfunctioning warning circuit. Suddenly he had only one option. After making the “Mayday!” call, he initiated the ejection sequence. Night is NOT the preferred time for a fighter pilot to find himself alone, in a parachute, and descending into a large body of water. But Tom Davis, as he had so often in the past, was up to the task. Although he had a terrific headache, he oriented himself enough to decide that he could paddle to land if he could get rid of his chute once he hit the water; then inflate his dingy and board it. Again he performed flawlessly, and eventually reached a beach in northwest Florida near Apalachicola Point. Alone, having survived an ejection and water landing, and now dog-tired, Tom shouted for help, set out his emergency flares, then walked up and down the beach trying to locate someone who could help him notify his unit that he was OK. Finally, and with his head still aching, he decided to wait until daylight for the searchers who would surely find him. The dinghy looked like as good a bed as he had available, and he decided to lay down with his head on the inflated side of the raft. When he did so, the fractured spine!! he had unknowingly suffered during the ejection, and the cause of his headache, shifted just enough to sever his spinal cord. He died instantly and painlessly, and was found the next day by searchers. Much of what I have written was deduced from his footsteps on the beach, the flares, and other indications of his last heroic moments. Tom Davis was a fighter to the end. On his last flight, he conducted himself with greatness and courage, just as he had done in every severe test of his young life. He was a GREAT fighter pilot. I felt pleased with my results, while my disappointments grew later, and I was eager to get home to my family. I had promised Martha we would meet at the Top of the Mark Hopkins on my return, and so it would be. I was flying by contract airline to San Francisco and we made the necessary arrangements, for the appointed day of my arrival. But our flight to the States was delayed by mechanical problems. Martha arrived, to announce to the desk staff that she was Mrs. Smith, whose husband Bob was in the hotel. The name Smith is suspect under such situations, one might suppose. It was evening and she was alone and terribly embarrassed by the questioning stares from the desk personnel, in a time when morality was at a higher norm than today’s broad coverage TV era. She had no idea when I would arrive, and I suppose it became clear to those folks because they granted her a room and I arrived the next day, to fulfill my promise of our happy reunion, in that grand hotel of the time. The next wonderful event was to get to my folks home in Albuquerque and begin the bonding process with Lane and Bobby. It was great and simple to establish a home and complete my leave without the usual cross-country household and family move. I arrived on leave within a few miles of my new assignment, and with the pleasure of working for and flying with Bones Marshall, again. I would find satisfaction in flying with a new mentor, friend and idol, Kenny Chandler, one-half of the pair that had unknowingly “challenged” me to learn the F-86 flip-over, my most challenging new maneuver. That Korean tour may have been less than what I wished for, from the standpoint of my accomplishments, but I learned to admire and respect some very wonderful men who showed me why the American fighting man was portrayed so elegantly in the movies. We may be spoiled by our blessings, but are empowered by pride in our country and America’s enduring integrity is part of us. I never forgot those B-29 crewmen, who virtually defenseless continued to targets, not because they were vital to a war effort, or the war was critical to our homeland, but because it was their duty to do it! The gruesome sight of the shredded B-29’s, which made it home with wounded and the dead is a different vision than the surreal though deadly game of fighter combat. Those bomber guys were the epitome of the American fighting spirit and models for the term Hero! And there were a large number of Americans, known captured during that war but were never heard of again. In fact, it was discovered after the break up of the USSR that many survived to be prisoners in Russia and at least one entire bomber crew was executed by firing squad, when their usefulness was served out. With people like them, and our troops who fought and serve in Iraq, why should we worry about what the Frenchmen think, or the Germans or the Russians? We saved them from each other so often that they despise us more for those embarrassing memories than our decisions or history of accomplishment. |

| previous section | next section |